the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Modelling seawater pCO2 and pH in the Canary Islands region based on satellite measurements and machine learning techniques

Irene Sánchez-Mendoza

Melchor González-Dávila

David González-Santana

David Curbelo-Hernández

David Estupiñán-Santana

Aridane G. González

J. Magdalena Santana-Casiano

Recent advancements in remote sensing systems, combined with new machine-learning model-fitting algorithms, have enabled the estimation of seawater carbon dioxide partial pressure (pCO2,sw) and pH (pHT,is) in the waters around the Canary Islands (13–19° W; 27–30° N). Continuous time-series data collected from moored buoys and Voluntary Observing Ships (VOS) between 2019 and 2024 were used to train and validate the models, providing a robust observational basis for satellite-derived estimates.

Among all models tested, bootstrap aggregation (bagging) performed best, achieving an RMSE of 2.0 µatm (R2>0.99) for pCO2,sw and 0.002 for pHT,is. Multilinear regression (MLR), neural networks (NN) and categorical boosting (CatBoost) also showed good predictive skill, with RMSE values between 5.4 and 10 µatm for pCO2,sw (360–481 µatm) and 0.004–0.008 for pHT,is (7.97–8.07). Using the most reliable model, we identified an increasing trend in pCO2,sw of 3.51±0.31 µatm yr−1, exceeding the atmospheric CO2 growth rate (2.3 µatm yr−1), alongside an acidification trend of −0.003 ± 0.001 yr−1.

Over the 2019–2024 period, rising atmospheric CO2 and increasing sea surface temperatures (reaching up to 0.2 °C yr−1 during the unprecedented 2023 marine heatwave) likely contributed to these trends. The Canary Islands region shifted from a weak CO2 source (0.90 Tg CO2 yr−1) in 2019 to 4.5 Tg CO2 yr−1 in 2024. After 2022, eastern sites that previously acted as annual CO2 sinks became net sources.

- Article

(13414 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(1131 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Anthropogenic emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) from fossil fuel combustion, cement production and land-use change (Doney et al., 2009; Le Quéré et al., 2009; Siegenthaler and Sarmiento, 1993; Zeebe, 2012) since the First Industrial Revolution have sharply increased atmospheric concentrations of this trace gas. This rise is partly mitigated by uptake from terrestrial vegetation and the oceans (Friedlingstein et al., 2025). The North Atlantic Ocean is reported as one of the major oceanic CO2 sinks in the Northern Hemisphere, absorbing 2.6 ± 0.4 Pg CO2 yr−1. This is equivalent to ∼ 25 % of the oceanic anthropogenic CO2 sink, based on 18 years of observations (Gruber et al., 2002).

Recent research has placed increasing emphasis on quantifying oceanic CO2 uptake and its impact (e.g., Bange et al., 2024; Gregor et al., 2024). A common approach involves using regression models to estimate surface ocean CO2 partial pressure (pCO2,sw) from environmental variables. However, these models often fall short in capturing the complexity of dynamic regions such as coastal zones and continental shelves (Sun et al., 2021). These areas exhibit intense physical and biogeochemical activity, driven by high rates of primary production, carbon burial, organic matter recycling, and calcium carbonate deposition (Boehme et al., 1998; Borges et al., 2005; Gattuso et al., 1998). Despite their importance, these regions remain poorly constrained in global carbon budgets and air-sea CO2 flux estimates (Dai et al., 2022).

Pioneering studies by Borges et al. (2005) and Cai et al. (2006) provided the first global assessments of coastal CO2 fluxes, emphasizing strong spatial heterogeneity and functional diversity of coastal ecosystems in the global carbon cycle. More recent studies indicate that coastal regions act as significant CO2 sinks, with global ingassing estimates of 0.54–1.47 Pg CO2 yr−1 (Cao et al., 2020; Laruelle et al., 2014), though updated assessments suggest lower rates (Dai et al., 2022; Regnier et al., 2022; Resplandy et al., 2024; Roobaert et al., 2019).

At large latitudinal scale, sea surface temperature (SST) is a primary driver of surface ocean pCO2,sw, often expressed as CO2 fugacity (fCO2,sw), which accounts for non-ideal gas behaviour due to molecular interactions and is typically slightly lower than pCO2 (Wanninkhof et al., 2022). At smaller spatial scales (within latitudinal bands), additional drivers such as upwelling-driven CO2 supply and biological uptake of dissolved inorganic carbon (CT) become relevant (e.g., Laruelle et al., 2014).

The pCO2,sw is governed by four interconnected processes: thermodynamic forcing, biological activity, physical mixing, and air-sea CO2 exchange (Fennel et al., 2008; Ikawa et al., 2013). One or two of these processes typically dominating in any given region (Bai et al., 2015). The thermodynamic component is primarily influenced by the SST and sea surface salinity (SSS), which determine CO2 solubility (Weiss, 1970) and carbonic acid dissociation constants (e.g., Lueker et al., 2000). Biological effects can be approximated using satellite-derived chlorophyll a (Chl a) and the diffuse attenuation coefficient of downwelling irradiance at 490 nm (Kd490) (Bai et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2019; Lohrenz et al., 2018). Vertical mixing processes, particularly those enriching surface waters with CO2 from deeper layers, are commonly parameterised using mixed-layer depth (MLD) (Chen et al., 2019). Additionally, the continuous rise in pCO2,atm, which drives the air-sea CO2 gradient, must be considered in long-term assessments.

Satellite remote sensing provides broad spatiotemporal coverage for surface pCO2,sw estimation (Chen et al., 2019). In the open settings with relatively variability, satellite-based estimates achieve RMSE < 17 µatm. Errors exceed 90 µatm in coastal waters due to increased complexity in physical and biogeochemical processes (Lohrenz et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2021). Traditional empirical approaches include multilinear (MLR) and nonlinear regression (MNR). Shadwick et al. (2010) applied MLR to the Scotian Shelf (R2=0.81; SE = 13 µatm). Signorini et al. (2013) reported RMSE of 22.4–36.9 µatm along the U.S. East Coast. Chen et al. (2016) developed a satellite-based model for the West Florida Shelf with RMSE < 12 µatm.

Machine learning (ML) approaches, such as neural networks (NN), random forests and CatBoost, have improved prediction skills. Lefèvre and Taylor (2002) reported NN residuals of 3–11 µatm in the subpolar gyre. Telszewski et al. (2009) obtained RMSE of 11.6 µatm in the North Atlantic. Sun et al. (2021) used CatBoost to reach RMSE of 8.25 µatm (R2=0.946). Gregor et al. (2024) applied ML with target transformation at the global scale (1982–2022), resolving 15 % more CO2 flux (FCO2) variance than traditional methods.

In coastal studies, Jo et al. (2012) used NN with SST and Chl a in the South China Sea (RMSE = 6.9 µatm; r=0.98). Duke et al. (2024) showed that nearshore outgassing reduces net flux in the Northeast Pacific. Roobaert et al. (2024) highlighted strong seasonal FCO2 variability driven by open-ocean and intracoastal exchanges. Wu et al. (2024) applied ML in the Gulf of Mexico, estimating 1.5 TgC yr−1 of CO2 uptake, though long-term trends remained uncertain.

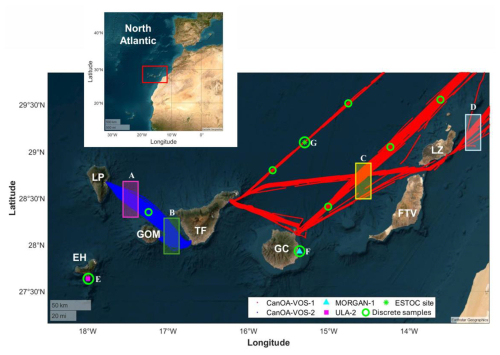

The present study focuses on the coastal Canary Islands basin (27.0–30° N; 13.0–19° W) (Fig. 1), located in oligotrophic waters of the eastern subtropical North Atlantic gyre (Pelegrí et al., 1996). The region is influenced by the Canary Current and trade winds, which generate mesoscale eddies. Despite low surface Chl a concentrations, primary productivity may increase due to upwelling filaments from NW Africa, eddies, and dust fertilization (Davenport et al., 1999). Marine heatwaves (MHWs) are intensifying under climate change (Frölicher and Laufkötter, 2018; Hobday et al., 2016; Holbrook et al., 2019). Varela et al. (2024) reported that 2023 was the warmest year in the Canary Upwelling System since 1982, with widespread record SST, likely affecting CO2 dynamics.

Figure 1Map of the Canary Islands showing the CanOA-VOS tracks (CanOA-VOS-1 Jona Sophie, in red; and CanOA-VOS-2 Benchijigua Express, in blue), the locations of the moored oceanographic buoys (MORGAN-1, cyan triangle; ULA-2, purple square), the ESTOC site (green star), and green circles indicate discrete sampling locations. The positions of sites A–F are also indicated, with site E corresponding to the ULA-2 buoy, site E to the MORGAN-1 buoy, and site G to the ESTOC site. The island acronyms are included (EH: El Hierro, LP: La Palma, GOM: La Gomera, TF: Tenerife, GC: Gran Canaria, FTV: Fuerteventura, LZ: Lanzarote). The figure was created with Matlab (version 2023b) software using the geoplot function with a satellite basemap. Basemap: Esri World Imagery (satellite imagery), © Esri and its data providers.

Long-term observations reveal a consistent rise in surface pCO2,sw in this region. Takahashi et al. (2009) estimated an increase of 1.8 ± 0.4 µatm yr−1 for the North Atlantic (1972–2006). Bates et al. (2014) reported 1.92 ± 0.92 µatm yr−1 (1996–2012) at the ESTOC (European Station for Timeseries in the Ocean Canary Islands) site, with pHT,is (pH in total scale and at in situ temperature) decreasing by −0.0018 ± 0.0002 yr−1. More recently, González-Dávila and Santana-Casiano (2023) reported pCO2,sw increasing by 2.1 ± 0.1 µatm yr−1 and pHT,21 decreasing by −0.002 ± 0.0001 yr−1 in the upper 100 m (1995–2023), around 20 % faster than rates for 1995–2010.

The aim of this study was to develop and validate a machine-learning algorithm to estimate pCO2,sw, pHT,is and FCO2 in the Canary Basin (NE Atlantic) using satellite-derived environmental variables and a high-resolution time series of pCO2,sw observations from voluntary observing ships (VOS) and moored oceanographic buoys.

2.1 Data

2.1.1 In situ observations

The observational dataset was compiled using measurements from Surface Ocean Observation Platforms (SOOPs) installed on Volunteer Observing Ships (VOS) and moored oceanographic buoys (Fig. 1; Table S1 in the Supplement). Two VOS collect continuous underway data along their routine shipping routes:

-

The CanOA-VOS-1 on board the Jona Sophie (formerly Renate P.) operated in Spain by Nisa Marítima and owned by Reederei Stefan Patjens GmbH & Co. KG. This cargo vessel services the eastern Canary Islands between Tenerife (TF; 28.4867° N, 16.2284° W), Gran Canaria (GC; 28.1319° N, 15.4185° W) and Lanzarote (LZ; 28.9682° N, 13.5294° W) and continues northeast of Lanzarote in route to Barcelona (Spain). Seawater is sampled from a depth of 7 m. CanOA-VOS-1 contributes to the Spanish component of Integrated Carbon Observation System (ES-SOOP-CanOA, ICOS-ERIC; https://www.icos-cp.eu/, last access: 22 January 2026) since 2021 and has been classified as an ICOS Class 1 Ocean Station.

-

The CanOA-VOS-2 on board Benchijigua Express, operated and owned by Fred Olsen Express, covering the western islands between a second port in Tenerife (TF; 28.0486° N, 16.7163° W), La Gomera (GOM; 28.0859° N, 17.1090° W) and La Palma (LP; 28.6751° N, 17.7666° W). The seawater intake is located at 5 m depth.

In addition, two coastal oceanographic buoys record surface data at 1 m depth:

-

MORGAN-1 (Gando, Gran Canaria, 27.9296° N, 15.3646° W; González et al., 2024).

-

ULA-2 (El Hierro, 27.6350° N, 17.9964° W).

All autonomous underway monitoring and data acquisition follows the quality-control procedures recommended by Pierrot et al. (2009). A detailed description of equipment can be found in Curbelo-Hernández et al. (2021, 2022) and in the Supplement. The number of used observations is listed in Table S1 in the Supplement.

Discrete samples of total alkalinity (AT) and total inorganic carbon (CT) were collected on board by a scientist on a transect every three months on the same seawater intake line used by the underway system, ensuring coverage across seasons and sampling sites (Fig. 1). Analyses were performed using a VINDTA 3C (Marianda™) following Mintrop et al. (2000). Calibration was carried out using Certified Reference Material (CRMs; provided by Andrew Dickson, Scripps Institution of Oceanography), with an accuracy of ± 1.5 µmol kg−1 for AT and ± 1.0 µmol kg−1 for CT. Differences between pCO2,sw (converted from measured xCO2,sw; for method see below) and discrete pCO2(AT,CT) (CO2sys.V2.1.xls, set of carbonic acid constants from Lueker et al., 2000, n=66) were 4 ± 4 µatm for the GO8050 and 7 ± 5 µatm for the ProCV system. A correction factor was applied to account for these offsets.

For regional comparison, seven locations were defined across the archipelago (Fig. 1): Site A, along the LP-GOM route (17.5 ± 0.05° W); Site B, along the GOM-TF route (16.95 ± 0.05° W). Site C, at the intersection of multiple ship routes (14.65 ± 0.05° W); Site D, near the NW African coast along the LZ-Iberian Peninsula route (13.2 ± 0.05° W); Site E, at the ULA-2 buoy near El Hierro; Site F at the MORGAN-1 buoy at Gando bay (GC); and Site G at the ESTOC site.

2.1.2 Satellite data

Satellite-derived SST, Chl a, Kd490, MLD data were used to develop the pCO2,sw and pHT,is forecast models, while wind speed was incorporated for FCO2 calculation. All satellite products were obtained from the Copernicus Marine Environmental Monitoring Service (CMEMS; https://marine.copernicus.eu/access-data, last access: 27 May 2025). Wind speed data were retrieved from the Agencia Estatal de Meteorología (AEMET; AEMET Open Data, https://opendata.aemet.es/centrodedescargas/productosAEMET, last access: 8 October 2025). Wind measurements were taken La Palma Airport (33 m), La Gomera Airport (15 m), Fuerteventura Airport (25 m), Lanzarote Airport (14 m), Gran Canaria Airport (24 m), and El Hierro Airport (32 m), corresponding to sites A–F of the study area. Wind speeds were standardised to 10 m height following Allen et al. (1998). All variables were processed and matched in time and space to the observational records, and daily means were used for model calibration and validation. The full daily dataset was then applied to generate the surface marine carbonate system variables in the Canary Islands.

Satellite-derived products carry inherent uncertainties associated with remote sensing retrievals. For the used CMEMS products, mean uncertainties were 0.62 °C for SST and 0.485 mg m−3 for Chl a. Their contribution to prediction error was assessed during model validation through comparison with coincident in situ measurements.

2.2 Variable determination and computational methods

The raw data were processed using MATLAB® R2019b and Python 3.13.6 (2023). For the VOS dataset, xCO2,sw measurement from the GO8050 system were calibrated using a four-standard procedure, after filtering data points collected near ports where seawater CO2 concentrations may be influenced by local activities. Quality control included applying minimum flow thresholds of 2.5 L min−1 for the seawater line and 50 mL min−1 for the LICOR© gas flow.

The partial pressure of CO2 in seawater (pCO2,eq) was calculated from corrected dry xCO2 (Dickson et al., 2007). Values from both VOS routes were subsequently adjusted to intake temperature to account for differences between the thermosalinograph/equilibrator temperature and SST (Takahashi et al., 1993). Fugacity (fCO2,sw) was then computed from pCO2,sw for both VOS and buoy datasets (Dickson et al., 2007). Discrete samples analysed for AT using the VINDTA 3C were used to determine an AT-SSS relationship for the study region (n=66), consistent with that previously reported for the ESTOC site (González Dávila et al., 2010). The normalised AT (NA) was 2290±3 µmol kg−1, significant at the 99 % confidence level (p-value < 0.01; r2=0.96), with no evidence of seasonal variability, in agreement with long-term ESTOC observation (González Dávila et al., 2010). This relationship was applied to compute total scale pHT,is(AT(SSS), fCO2,sw) for the Canary Region (González Dávila et al., 2010). All process variables were averaged to a daily resolution.

Daily mean atmospheric xCO2,atm was obtained from onboard atmospheric measurements and compared with records from the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) Izaña Atmospheric Observatory (AEMET, 2024) in Tenerife (28°18′ N, 16°29′ W), due to potential contamination by ship operations. Winter maxima were similar between datasets (±1.5 µatm), while late summer minima at Izaña were on average 3 µatm higher than values measured at the ship's 10 m inlet. As in situ coverage was limited and the Izaña record provided a longer continuous series, the Izaña xCO2,atm dataset was adopted for this study. Atmospheric xCO2,atm was converted to pCO2,atm (Dickson et al., 2007).

The flux of CO2, FCO2, was determined using Eq. (1):

where 0.24 is the conversion factor to express the flux in mmol m−2 d−1, S is the solubility of CO2 in seawater (Weiss, 1970), ΔpCO2 is pCOCO2,atm and k is the gas transfer rate determined using the Wanninkhof (2014) parameterization (Eq. 2):

where u is the wind speed (m s−1) and Sc is the Schmidt number.

Equation (1) was applied to the daily modelled data. Daily fluxes were averaged to provide monthly fluxes, which are reported as daily average value for each month (mmol m−2 d−1).

Each physicochemical variable y (including pCO2,atm and fCO2,atm) was fitted to a harmonic function (Eq. 3, where t is the year fraction for each observation). Seasonal anomalies were obtained by adding the residuals between observed values and those predicted by Eq. (3) to the constant term a in Eq. (3), representing the mean value of y for the study period. Interannual trends were then estimated using Eq. (4) applied to the deseasonalised time series. Although the length of the dataset is relatively short (5–6 years), the use of detrended seasonal anomalies minimizes end-effects and improves the robustness of the trend estimation.

2.3 Model fitting and statistical treatment

Statistical analyses were conducted using R (R Core Team, 2019). Machine-learning methods were used to fit the different models. The dataset was initially partitioned into training (80 %) and validation (20 %) subsets, with allocation performed randomly at the cruise level to avoid temporal bias. This random split was repeated for each model run to ensure representative sampling. Once model performance had been evaluated, the complete dataset was used to provide the optimal model parameters.

The simplest fitted model was a multiple linear regression (MLR), defined analytically in Eq. (5):

where and are the estimated coefficients for each predictor and ϑ the residuals. The same equation (without the term) was used to model pHT,is dependence.

Three machine-learning techniques were used: neural network (NN; Wang, 2003), categorical boosting (CatBoost; Dorogush et al., 2018; Prokhorenkova et al., 2018; Qian et al., 2023) and bootstrap aggregation (bagging; Breiman, 1996).

These approaches are widely employed in environmental modelling and provide complementary approaches for improving predictive accuracy by reducing variance and capturing nonlinear relationships.

CatBoost is a gradient-boosting algorithm that constructs decision trees sequentially and efficiently handles categorical features, minimising information loss. Its ordered-boosting framework reduces prediction shift associated with gradient bias (Dorogush et al., 2018; Prokhorenkova et al., 2018; Qian et al., 2023; Sun et al., 2021).

Neural Networks (NN) are flexible nonlinear models inspired by the human brain, capable of capturing complex relationships between inputs and outputs (Wang, 2003). These methods are composed of interconnected neurons arranged in layers: an input layer representing predictors, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer producing the final prediction.

Bootstrap aggregation (bagging) is an ensemble technique that improves predictive robustness by generating multiple versions of a model trained on different bootstrap samples of the dataset (Breiman, 1996). Predictions are then averaged to reduce variance and prevent overfitting, making the overall model more stable and reliable.

Model performance was assessed using the validation dataset through the coefficient of determination (R2), root mean square error (RMSE; Eq. 6), mean absolute error (MAE; Eq. 7), and daily sum of squared errors (SSE; Eq. 8).

where pCO2,i and are the observed and modelled pCO2, N is the number of observations and d is the number of days in the dataset.

The Akaike information criterion corrected for a finite dataset (AICc) was determined using Eq. (9). It evaluates the balance between goodness-of-fit and model complexity (i.e., number of predictors). Among competing models, the one with the lowest AICc is considered the most appropriate.

where k is the number of parameters involved in the model, ln (L) is the log-likelihood for the predicted model and n is the number of observations.

To estimate the coefficients of each seasonal model and determine confidence intervals, two assumptions were tested: (1) normality of residuals, assessed using the two-Welch Shapiro-Wilk test (α=0.05) and quantile-quantile plots, and (2) homogeneity of residual variance (homoscedasticity), assessed graphically. When the normality assumption was not met, bootstrapping was used to determine confidence intervals. Model comparisons were performed using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) and analysis of variance (ANOVA) to detect significant differences at α=0.05.

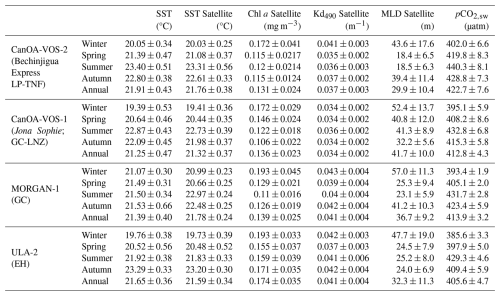

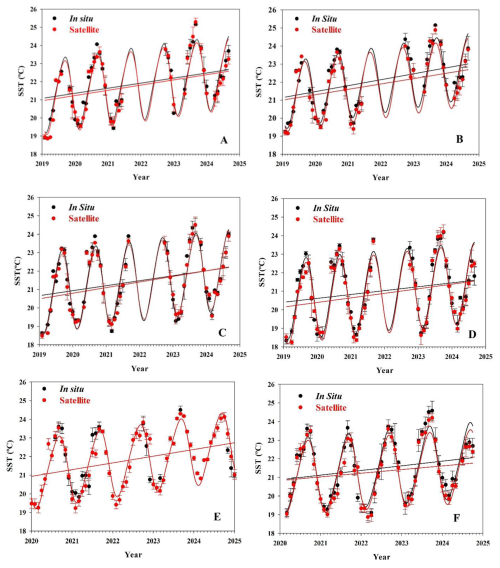

The observational data enabled the construction of a database for modelling the behaviour of pCO2,sw and pHT,is in the Canary Basin. To characterise the measured and satellite-derived parameters used in this study, Table 1 summarises their seasonal mean and standard deviations for each observation system. In situ SST (Fig. 2) showed a clear seasonal cycle, with maximum temperatures in summer (July–September) and minima in winter (January–March). The highest SST occurred in the westernmost sector of the archipelago (between La Palma and Tenerife), averaging ∼ 1 °C warmer than the eastern sector (between Gran Canaria and Lanzarote). A similar seasonal and longitudinal pattern was observed for pCO2,sw and pHT,is (Table 1). Seasonal and annual SST means derived from in situ and satellite observations differed by ∼ 0.15 °C on average.

Table 1Seasonal mean and standard deviations of observational data (pCO2,sw and SST) and satellite-derived data (SST, Chl a, Kd490 and MLD) used in this study. The locations listed in the first column correspond to the two ship routes (CanOA-VOS-1 Jona Sophie and CanOA-VOS-2 Benchijigua Express) and the two moored buoys (MORGAN-1 and ULA-2).

Figure 2Monthly mean in situ SST (black) obtained from ship-based observations and moored buoys, and satellite-based SST (red) at locations (A)–(F). Harmonic fittings (Eq. 4) of the data are shown together with the linear fitting for the seasonally detrended data. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the measurements.

3.1 Variability of the SST data

Figure 2 shows the monthly mean SST derived from observations and satellite products at sites A–F. A clear seasonal cycle is evident across sites, with maximum SST in September (24.20 ± 0.76 °C in the western sites at A–B and 23.70 ± 0.68 °C in the eastern sites C–D) and minima in March (19.47 ± 0.24 and 18.97 ± 0.31 °C, respectively). Anomalous high SST were recorded during summer 2023, exceeding 25 °C at sites A–C and 24 °C at site D. The seasonal amplitude was 4.2 ± 0.4 °C along CanOA-VOS-1 and 4.5 ± 0.5 °C along the CanOA-VOS-2. Although no significant differences were found between sections within the same region (A vs B and C vs D), the mean SST at site D (20.59 ± 0.09 °C) was slightly lower than at site C (21.00 ± 0.09 °C). The covariance analysis between observational and satellite SST shows no significant differences between datasets (p<0.05). The mean daily residuals were 0.16 °C (SE = 0.12 °C) in the western region and 0.12 °C (SE = 0.10 °C) in the eastern region.

A seasonal SST cycle was evident at site E, despite the scarcity and temporal gaps of the ULA-2 buoy (Fig. 2E). Using the year with the most continuous data (2021), the seasonal amplitude was 5.10 ± 0.18 °C, with maximum SST in September (24.70 ± 0.26 °C) and minimum values in March (19.60 ± 0.40 °C). A comparable pattern was observed at site F from the MORGAN-1 buoy record (Fig. 2F), with SST peaking in September (23.71 ± 0.47 °C) and reaching its lowest in March (19.46 ± 0.52 °C), corresponding to a seasonal amplitude of 4.22 ± 0.51 °C.

Longitudinal variability in SST from both CanOA-VOS and satellite records is shown in Figs. 2 and S1 in the Supplement. In the western region, observed SST ranged from 20.59 ± 0.09 °C in winter to 24.04 ± 0.13 °C in summer, with an annual mean of 22.45 ± 0.11 °C. Seasonal averages matched those calculated from the satellite-derived data (0.1–0.2 °C), with the largest differences occurring in summer (0.26 °C). Although SST in the eastern region were lower throughout the year (annual mean 21.02 ± 0.27 °C), influenced by the Northwest African upwelling, similar seasonal variations were found (from 19.19 ± 0.24 °C in winter to 22.82 ± 0.25 °C in summer). Differences between in situ and satellite SST were smaller than those in the western region (0.05–0.2 °C). The west-east SST decrease persisted consistently along the longitudinally monitored span of the Canary archipelago, except for a slight warming associated with the island wake effect south of Tenerife captured along the CanOA-VOS-2 route (Fig. S1).

3.2 Predictive models of pCO2,sw

Daily averaged pCO2,sw and SST from all observational platforms, together with coincident satellite-derived chlorophyll a and MLD data at the same location, were used to train the four predictive models.

3.2.1 Multiple linear regression (MLR)

The first set of models used traditional multiple linear regression (MLR) to provide an initial, simple approximation of pCO2,sw prediction. Five model configurations were tested, using different combinations of the available predictors: pCO2,atm, SST, Chl a, Kd490 and MLD, following the analytical form in Eq. (5). Considering the strong correlation between Chl a and Kd490 (R2=0.96), Kd490 was deemed non-significant and excluded from further analysis. The coefficients obtained for each configuration are listed in Table 2.

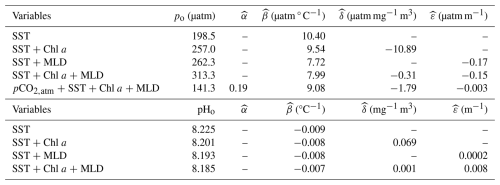

Table 2Regression coefficients obtained from the multiple linear regression models for pCO2,sw (top) and pHT,is (bottom), applied to the different predictor combinations according to Eq. (5), using the full dataset.

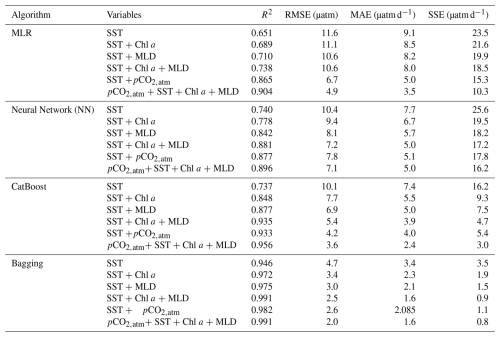

Model selection based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AICc<2) together with performance statistics (Table 3) suggest that the best-performing MLR included the atmospheric CO2, thermal, physical and biological drivers (pCO SST + MLD + Chl a). However, a two-variable model (SST and pCO2,atm) produced comparable accuracy. Figure S2 shows measured versus predicted values for the training and validation datasets using four variables, pCO SST + MLD + Chl a. Although many measured and predicted pCO2,sw showed small differences, considerable scatter was observed, reflected in the performance metrics (Table 3). Validation results (Table S2) were consistent with training performance.

3.2.2 Machine learning techniques

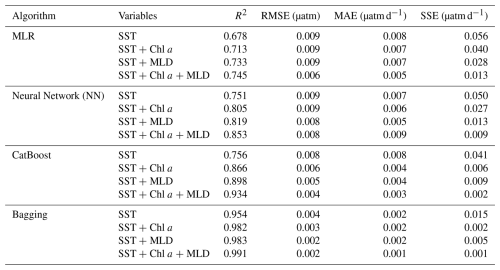

Table 3 compares the performance of the machine-learning approaches trained using observational pCO2,sw data. All models were developed using the same dataset and input variables.

Neural Network (NN)

The first machine-learning method applied to predict pCO2,sw was a neural network (NN). The performance metrics are presented in Table 3.

No analytical expression is provided, as the learned relationships are embedded within the synoptic weights of its neurons. Statistics indicate similar performances between the three-variable models (SST + MLD + Chl a) and the four-variable model, including pCO2,atm, where two-variable models performed only slightly less effectively. Scatter plots of measured versus predicted pCO2,sw for both training and validation datasets using the best NN model are shown in Fig. S2. Overall agreement was good, although prediction dispersion increased at higher pCO2,sw, suggesting slightly poorer fitness in this range. For the training dataset, RMSE, MAE, SSE, and R2 were 7.1 µatm, 5.0 µatm d−1, 16.2 µatm2 d−1, and 0.891, respectively.

Categorical boosting (CatBoost) regression

The second machine-learning method applied to predict the pCO2,sw in the Canary Archipelago was CatBoost. A total of 500 iterations were used to generate the prediction model. The performance statistics for all model configurations are summarised in Table 3. The pCO SST + Chl a + MLD configuration yielded the best results, achieving the lowest RMSE, MAE and SSE, and the highest R2. The performance of this model (Fig. S2), applied to both the training and validation datasets, yielded an R2 greater than 0.95 with an RSME of only 3.6 µatm. The training dataset provided the most accurate results, with an MAE of 2.4 µatm d−1 and an SSE of 3.0 µatm2 d−1. The validation statistics were consistent with those obtained during the training phase (Table S2).

Bootstrap aggregating (bagging) regression

A bagging algorithm was applied to predict pCO2,sw using 200 bootstrap replicates. The computed statistics for the training set, combining the different parameters controlling the pCO2,sw are summarised in Table 3.

Based on the statistical analysis, the models with the best predictive capacity were those that considered three or four parameters, as they yielded lower RMSE, MAE, and SSE. As observed in the previously fitted models, those including SST + MLD or SST +pCO2,atm also performed well (Table 3). The bagging algorithm provided the highest R2, lowest RMSE, MAE and SSE (0.991, 2.0, 1.6, 0.8, respectively) for any combination of variables, even when only SST was considered. The plot of measured versus predicted pCO2,sw for both the training and validation sets using a four-variable model is shown in Fig. S2. This model presented low RMSE, MAE, and SSE (2.0 µatm, 1.6 µatm d−1, and 0.8 µatm2 d−1, respectively). In this scenario, the application of the model to the validation set showed greater data dispersion than the training set (Table S2), due to the smaller sample size (Fig. S2).

3.3 Predictive models for pHT,is

pHT,is predictions were generated from the computed pHT(AT(SSS), fCO2), using observations and satellite data (interpolated to the time and location of each observation) as input variables. In this case, pCO2,atm was excluded from the predictive variables to avoid redundancy. Table 4 shows a comparison of the models employed in the machine-learning-based approaches. It is important to note that all models were developed using the same dataset and input variable.

Table 4Performance metrics for the comparison between predicted and measured pHT,is for each model using the training dataset.

3.3.1 Multiple linear regression (MLR)

The coefficients obtained for each of the four combination models are shown in Table 2. The statistical performance of these models is presented in Table 4. As observed for the pCO2,sw fitting, the model including SST + Chl a + MLD provided the best performance for pHT,is, with an R2 of 0.745 and an RMSE of 0.006. The plot of measured versus predicted pHT,is for model training (Fig. S3) shows a distribution similar to that of the validation dataset. This indicates that the number of data points used for validation was not a limiting factor for the model.

3.3.2 Machine learning techniques

All three techniques yielded higher correlation coefficients than those obtained using MLR (Table 4). The performance of the NN was lower than that of CatBoost, while bagging showed the best performance across all models. The model including three variables (SST + Chl a + MLD) was the most accurate for predicting pHT,is in all cases (Table 4), with an R2 of up to 0.99 and an RMSE as low as 0.002 when applying the bagging technique. Every combination of satellite data, even when considering only the SST, resulted in an R2 greater than 0.95 with bagging. For CatBoost, the three-variable model was required to achieve an R2 above 0.93.

We compared the accuracy indicators for the training and validation datasets for the three-variable models (Tables 4 and S3, Fig. S3) within the pHT,is range of this study (7.97–8.07). When applying machine learning techniques, bagging consistently provided the best fit, ad increasing the data volume improved determination. RMSE, MAE, and SSE for both training and validation datasets remained below 0.01 in pH, reaching 0.002 and 0.003, respectively, when using bagging.

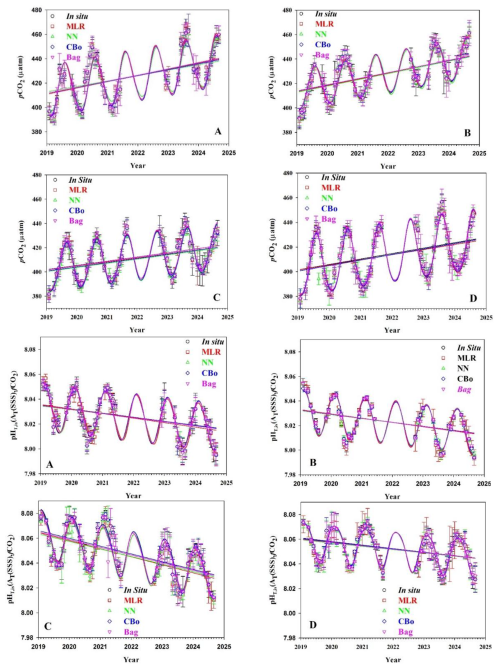

3.4 Validation of the results

The best prediction models for each class, based on the evaluated statistical parameters, were used to reconstruct the monthly mean pCO2,sw and pHT,is at sites A–D, and the results were compared. The temporal variability of observed and predicted values is presented in Fig. 3. All models successfully reproduced the seasonal cycle: pCO2,sw reached its maximum in March and its minimum in August-September, while pHT,is exhibited the opposite pattern. The predictions showed minor but statistically non-significant differences relative to the observations (p>0.05). No significant differences were detected among the linear, NN, CatBoost models (p<0.05). When comparing bagging predictions with observational data, no significant differences were found, confirming that boostrap aggregation yielded the most accurate representation of the measured values. Overall, observed pCO2,sw were slightly higher than predicted ones, with mean differences of 1.7 ± 1.8 µatm for pCO2,sw and 0.002 ± 0.001 for pHT,is.

Figure 3Monthly means of observational-based and model-predicted pCO2,sw(pCO2,atm, SST, Chl a, MLD) and pHT(SST, Chl a, MLD) at the locations A–D (Fig. 1). MLR (red) means multilinear regression, NN (green) means neural network, CBo (blue) means CatBoost and Bag (purple) means bagging. Linear fittings for the seasonally detrended data are plotted.

Statistical differences (p>0.05) were detected when comparing the western and eastern sectors by ANCOVA. At sites A and B (Fig. 3), pCO2,sw (and pHT,is) varied seasonally between 404 ± 18 µatm (8.045 ± 0.012) and 449 ± 19 µatm (8.004 ± 0.010), with seasonal amplitudes of 47 ± 8 µatm (0.049 ± 0.005). At sites C and D (Fig. 3), seasonal values ranged between 390 ± 15 µatm (8.069 ± 0.008) and 440 ± 16 µatm (8.028 ± 0.012), with amplitudes of 52 ± 7 µatm (0.038 ± 0.006).

Three oceanographic variables (SST, Chl a and MLD) with high-resolution satellite coverage for oceanic surface seawater, together with atmospheric CO2 partial pressure, were used to model pCO2,sw and pHT,is in the Canary Archipelago. Salinity was excluded from the fitted models due to its negligible influence on pCO2,sw variability (Sarmiento et al., 2007; Shadwick et al., 2010). Furthermore, satellite-derived salinity has been shown to differ considerably from in situ measurements, exhibiting elevated variability and uncertainty (Yu, 2020). Although Kd490 was included in the initial model tests, its lack of statistical significance is likely due to its strong correlation with Chl a (R2=0.96), making it redundant and therefore not retained as a predictor.

4.1 The Canary Region during 2019–2024: Observational and modelling data

In the Canary Islands, the highest temperatures (Fig. 2) were recorded in late summer (September), driven by enhanced stratification of the water column and increased solar radiation. The lowest temperatures were measured in winter (February–March) due to convective mixing induced by surface cooling of the water column. This seasonal behaviour is consistent with the hydrographic conditions described at the ESTOC site, where surface waters exhibit a seasonal temperature amplitude of 4–6 °C, with minimum and maximum temperatures of 18 and 24 °C, respectively, recorded before 2023 (González-Dávila and Santana-Casiano, 2023). This range is also comparable to the SST observed in the easternmost region covered by the CanOA VOS-1 during 2019–2020 (Curbelo-Hernández et al., 2021).

The statistically significant differences (p<0.05) observed between the western and eastern sections are related to their distance from the African continent. The easternmost part of the archipelago is more exposed to upwelling filaments (Davenport et al., 1999), whereas the westernmost part is partially sheltered by the islands themselves. This spatial pattern, clearly visible in Figs. 2 and S1 as a progressive decrease in SST towards the African coast, is well captured by satellite observations. Their validation showed no significant differences (p<0.05), even near the islands. Therefore, satellite data were deemed suitable for model fitting and subsequent parameter estimation.

MORGAN-1 data (site F) show anomalously high SST during the summer of 2023, consistent with the occurrence of extreme SST conditions in the Canary Upwelling System in 2023 (Varela et al., 2024). Satellite data at the coastal buoy locations also showed anomalously high summer values, although these were on average 0.3 °C lower than those measured by the buoy sensors. In situ temperatures from June to October 2023 were more than 1 °C higher than those recorded in previous years. These elevated temperatures were not observed in 2024, indicating that 2023 should be considered an anomalous year in this region.

It is noteworthy that SST during February–March 2024 remained high. Winter SST (JFM) increased in 2024 and was, on average, 1 °C warmer than in the previous years (average for 2020–2022 was 19.09 ± 0.20 °C; average for 2023–2024 was 20.01 ± 0.25 °C). These anomalies strongly influence the trends observed in both satellite and observational datasets.

Harmonic fitting of temperature (Eq. 4) for the period March 2020 to March 2023, despite the limitation of only three years of data, indicates a warming trend of 0.03 °C yr−1 in the seasonally detrended Gando Bay dataset (González et al., 2024). This rate is comparable to warming rates trends reported at the ESTOC site for the period October 1995 to March 2023 (González-Dávila and Santana-Casiano, 2023) and for the full Canary Upwelling System over 1982–2023 (Varela et al., 2024).

When considering the full five-year seasonally detrended in situ dataset from Gando Bay (March 2020 to October 2024), the warming rate increases to 0.19 ± 0.06 °C yr−1 (0.14 ± 0.06 °C yr−1 when derived from monthly mean satellite data). This SST increase was also observed at sites A–D (Fig. 2), where warming rates over the six years from February 2019 to October 2024 ranged from 0.29 ± 0.03 °C yr−1 at sites A–C to 0.21 °C r−1 at site D. The mean temperature at the western station (ULA-2) was ∼ 1 °C higher (22.12 ± 0.16 °C) than at the eastern station F (MORGAN-1; 21.13 ± 0.12 °C), reflecting the influence of Northwest African upwelling and island coastal upwelling. ANCOVA applied to both buoy datasets showed no significant differences between in situ and the satellite-derived SST, with mean differences below 0.19 °C, comparable to the regional mean difference of 0.15 °C for the full Canary dataset.

Satellite-derived data were used to predict pCO2,sw and pHT,is. The neural network model exhibited the highest prediction error (RMSE = 7.1 µatm, R2=0.896), whereas the MLR model performed slightly better (RMSE = 4.9 µatm, R2=0.904 for pCO2,sw). Previous studies applying MLR along the US coasts reported RMSE values ranging from 22.4 to 36.9 µatm (Signorini et al., 2013), while NN-based approaches in the North and South Atlantic Ocean yielded RMSE values exceeding 19 µatm (Ford et al., 2022) and 21.68 µatm (Friedrich and Oschlies, 2009), respectively. In comparison, both MLR and NN models applied in the present study perform favourably, likely due to the limited spatial domain and the extensive observational dataset. For pHT,is estimation, RMSE as low as 0.006 and 0.008 were obtained for MLR and NN, respectively, which fall within the typical analytical uncertainty.

The CatBoost empirical algorithm estimated pCO2,sw and pHT,is with uncertainties below 4 µatm and 0.004 pH, respectively, and R2>0.93 for both variables. This demonstrates robustness to uncertainty in satellite-derived variables influenced by different processes and coastal proximity, supporting its applicability in the region. However, the bagging approach exhibited exceptional performance, yielding uncertainties of 2.0 µatm for pCO2,sw and 0.002 pH for pHT,is over the period 2019–2024.

These particularly favourable results, and the comparatively low errors relative to ocean-scale models, likely arise because variability in pCO2,sw and pHT,is in the Canary Island waters is largely dominated by thermal effects (González-Dávila and Santana-Casiano, 2023; Takahashi et al., 2002). In this region, thermal control of surface carbonate chemistry is effectively captured by satellite-derived SST. In all cases, models using SST alone showed high correlation coefficients (). Although not the best-performing configurations, these single-variable models provide a reasonable representation of observed variability. The coefficient estimated from annual linear regression (10.40 µatm °C−1, Table 2) deviates from the theoretical regional rate for 2019–2024 (16 µatm °C−1; Takahashi et al., 2002), likely reflecting the influence of biological and physical processes (i.e., primary production, remineralisation and water mass mixing). Nevertheless, this rate remains consistent with those reported for ESTOC (Santana-Casiano et al., 2007).

Across all four sites and in Gando Bay, both observational data and model predictions indicate that pCO2,sw increased between 2019 and 2024 at a rate of 3.8 ± 0.6 µatm yr−1. The pHT,is decreased at a rate of −0.004 ± 0.001 yr−1 over the same period. Previous analyses at ESTOC for 1995–2023 (González-Dávila and Santana-Casiano, 2023) and at Gando Bay (site F) for 2020–2023 (González et al., 2024) reported a pCO2,sw increase of 2.1 ± 0.1 µatm yr−1 and a pHT,is decrease of −0.002 ± 0.001 yr−1. Comparable rates are observed across all selected sites when restricting analysis to March 2019–March 2023, excluding the anomalous conditions observed in late 2023, consistent with González et al. (2024).

4.2 Monthly pCO2,sw and pHT,is gridded maps

The bagging technique was used to construct gridded monthly maps of pCO2,sw and pHT,is for the Canary region (13–19° W, 27–30° N) over the study period. Results for the year 2023 are presented in Fig. 4. Monthly experimental averages are shown alongside the model predictions to illustrate the accuracy of the estimates. The expected seasonal pattern was reproduced, with higher pCO2,sw in September and lower in March, and the opposite behaviour for pHT,is. A clear longitudinal gradient was observed, with higher pCO2,sw and lower pHT,is toward the eastern sector, primarily driven by the thermal effect. Cooler seawater in the east, together with the influence of nutrient-rich, lower-pH Northeast African upwelled seawater (Pelegrí et al., 2005), counteract each other, increasing mean values while reducing seasonal amplitude.

Figure 4Gridded maps for pCO2,sw (left) and pHT,sw (right) predicted with bagging for the full March (Mar), June (Jun), September (Sep) and December (Dec) 2023 using pCO2,atm and satellite conditions of SST, Chl a, and MLD together with observational data available for that month (the same colour code was used). Figure produced with Ocean Data View (Schlitzer, 2021; https://odv.awi.de, last access: 10 July 2025).

Several oceanographic features are apparent. Upwelling filaments, characterised by lower temperatures, locally reduce pCO2,sw. In contrast, leeward island wake zones exhibit warmer waters, leading to increased pCO2,sw and decreased pHT,is. The African coastal upwelling signal is particularly evident in June and September, when lower pCO2,sw and higher pHT,is are observed as a result of enhanced biological activity that partially offsets the CO2-rich upwelled waters.

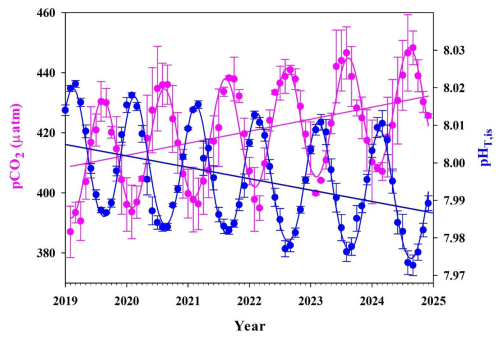

Monthly mean pCO2,sw and pHT,is for the Canary Basin, predicted using the bagging approach for the period 2019–2024, are shown in Fig. 5. Monthly means were computed by applying the bagging model to daily satellite-derived SST, Chl a, and MLD, together with pCO2,atm, and subsequently averaging the results spatially and temporally. Over these six years, mean pCO2,sw was 419.7 ± 16 µatm, with a seasonal amplitude of 55 µatm. Harmonic fitting (Eq. 4) of the predicted time series indicates an increasing trend of 3.51 ± 0.31 µatm yr−1 for 2019–2024, exceeding the contemporaneous increase in pCO2,atm (2.3 µatm yr−1).

Figure 5Monthly means of pCO2,sw (µatm) and pHT,sw predicted with bagging for 2019–2024 for the entire Canary region (27–30° N, 13–19° W). Linear fittings for the seasonally detrended data are also plotted.

Predicted pHT,is (Fig. 5) ranged from 8.015 ± 0.049 in February–March to 7.980 ± 0.058 in September–October, reflecting a seasonal decrease of ∼ 0.04 pH from winter to summer. Elevated winter values reflect lower temperatures and enhanced convective mixing, whereas lower summer values are attributed to biological activity and water-column stratification (Santana-Casiano et al., 2001, 2007). This seasonal pH decrease is partially offset by the thermal effect, which compensates for approximately 33 % of the total decline. The thermal contribution corresponds to a pH decrease of 0.06 associated with a temperature increase of 4.1 °C. This compensating effect is evident near the African coast (Fig. 5), where upwelling of deep, cold, CO2-rich waters reduces both SST and pH, generating a pronounced longitudinal gradient across the Canary region.

Figure 5 further shows that pHT,is declined throughout the study period due to increasing ocean acidity, with a rate of −0.003 ± 0.001 yr−1 derived from seasonally detrended data. The strong influence of MHW events, particularly during summer 2023 and winter 2023–2024, on the interannual trends of both variables is evident. The rise in pCO2,atm is accompanied by an increase in SST of 0.2 °C yr−1 over the six years, equivalent to a cumulative warming of 1.2 °C between 2019 and 2024. This increase is largely driven by the anomalously warm conditions in 2023, higher SST in winter 2020 compared to 2019, and elevated winter SST in 2023 and 2024 relative to 2022, when winter temperatures dropped below 18 °C and have since remained near 19 °C. These conditions have contributed to higher recent trends in pCO2,sw and ocean acidification relative to long-term estimates at ESTOC, which were 2.1 µatm yr−1 and −0.002 yr−1, respectively, for the period 1995 to early 2023 (González-Dávila and Santana-Casiano, 2023). The limited six-year time series may also contribute to the magnitude of the observed rates. Notably, winters with SST exceeding 19 °C and summers with SST above 25 °C had not been recorded at the ESTOC site before 2023.

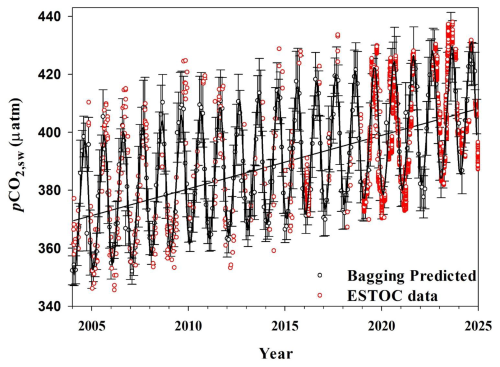

4.3 Long-term model prediction at ESTOC site

The bagging predictive model developed using data from the period 2019–2024 was applied to the ESTOC site for the period 2004–2024. Earlier years were not considered because the monthly satellite data before this period had lower spatial resolution. Satellite-derived SST, Chl a, and MLD, together with atmospheric pCO2 computed from xCO2 measurements at the Izaña (IZO) station, were used as model inputs (https://gml.noaa.gov/aftp/data/trace_gases/co2/flask/surface/txt/co2_izo_surface-flask_1_ccgg_event.txt, last access: 26 May 2025). Estimated values at 29°10′ N and 15°30′ W were compared with in situ observations from ESTOC (González-Dávila and Santana Casiano, 2023), updated to 2024, and are shown in Fig. 6. The model reproduced the ESTOC observations with mean residuals of 1.3 ± 3.1 µatm and yielded consistent trends of 1.9 ± 0.1 µatm yr−1 over the study period, as determined from both model output and the seasonally detrended observational data.

Figure 6Monthly means of pCO2,sw (µatm) predicted with bagging considering pCO2,atm, SST, Chl a, MLD for the period 2004–2024 at the location of the ESTOC site (G in Fig. 1) and measured ESTOC pCO2,sw.

When models excluding pCO2,atm were applied, residuals increased to values exceeding 2 µatm, particularly during the early part of the record (2004–2010), when residuals approached 4 µatm. This behaviour reflects the increased weighting assigned to SST in the absence of atmospheric forcing, especially during periods characterised by strong thermal anomalies such as the 2023 marine heatwave in the Canary Upwelling System. Analysis of satellite-derived SST at the ESTOC site for 2004–2024 shows minimal temperature variability during 2004–2019 (0.0012 ± 0.002 °C yr−1), followed by a marked warming trend during 2019–2024 (0.21 ± 0.01 °C yr−1), consistent with the behaviour observed at sites A–F (Fig. 1). Consequently, when models based solely on SST, Chl a and MLD were applied to earlier periods, lower pCO2,sw trends were predicted. In contrast, inclusion of pCO2,atm in the model allows both thermal and atmospheric contributions to pCO2,sw to be accounted for, ensuring that periods with weak SST trends still reflect the concurrent rise in atmospheric CO2 and its influence on surface seawater pCO2.

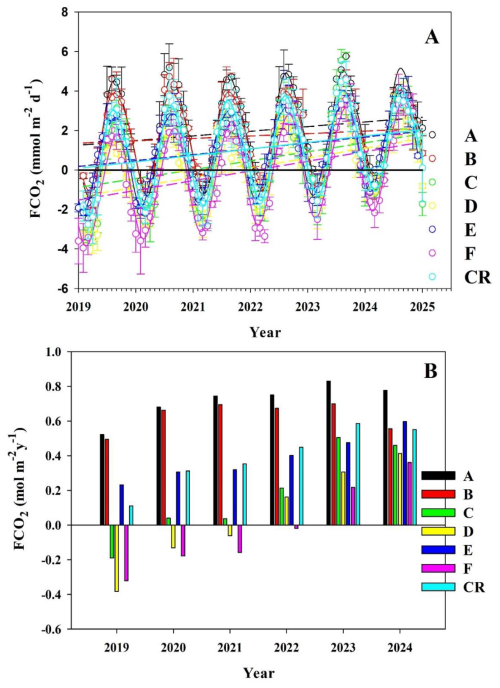

4.4 Air-sea CO2 exchange in the Canary Archipelago

The predicted pCO2,sw is highly useful for estimating FCO2 with improved spatial and temporal resolution. Figure 7 shows FCO2 calculated using the parametrisation proposed by Wanninkhof (2014) under monthly mean conditions for the period 2019–2024. The seasonal cycle of FCO2 is primarily controlled by the large seasonal variability in pCO2,sw, which governs ΔpCO2, as pCO2,atm exhibits a much smaller seasonal amplitude. In contrast, the effect of wind speed and gas solubility exhibits a smaller seasonal amplitude (Landschützer et al., 2014).

Figure 7(A) Monthly means of FCO2 (mmol m−2 d−1) in the Canary archipelagic waters predicted with bagging from 2019 to 2024 and (B) net annual FCO2 (mol m−2 yr−1). In both plots, FCO2 was represented at locations A–F and for the entire Canary Region (CR). Linear fittings for the seasonally detrended data are also plotted.

The region acts as a strong CO2 sink during winter and spring, whereas during the warm season it behaves as a source. During the warm period from late May to early September (González-Dávila et al., 2003), when the dominant trade winds impact the Canary Islands, pCO2,sw exceeds pCO2,atm. This leads to higher wind speeds and reinforces the role of CO2 supersaturation in the total flux estimation, favouring the region's role as a CO2 source.

Sites located closer to the African continent (C and D) and the coastal waters (F in the Gando Bay, also in the eastern part of the Canary Islands) are more likely to act as a CO2 sink than the westernmost region (Curbelo-Hernández et al., 2021). This behaviour is primarily associated with the thermal gradient, with temperatures more than 1 °C lower than in the western sector, as well as with higher biological productivity. However, Fig. 7B shows that, due to the increase in SST across the Canary Islands during the study period, all locations that previously acted as an annual CO2 sink shifted to behaving as a source after 2022.

For the period 2019–2024, the Canary region acted as a weak CO2 source, with a mean flux of 0.39 ± 0.17 mol m−2 yr−1. Increasing flux trends were observed across all sub-regions, ranging from 0.18 to 0.37 mmol m−2 d−1, with an average rate of 0.25 ± 0.02 mmol m−2 d−1. When considering the entire Canary region (13–19° W, 27–30° N), covering an area of 185 000 km2 after excluding the island land masses, the system transitioned from a weak source of 0.9 Tg CO2 in 2019 to a source of 4.5 Tg CO2 in 2024, with a maximum of 4.8 Tg CO2 in 2023. This peak coincided with the highest SST recorded during the study period (Fig. 2), favouring the largest increase in pCO2,sw.

These estimates are primarily based on surface water measurements, particularly those derived from satellite data. Although such datasets provide high spatial resolution and robust representation of surface trends, they do not capture subsurface processes or vertical gradients in CO2 and temperature.

This study presents the first predictive modelling framework for surface seawater pCO2,sw and pHT,is in the Canary Islands basin. The results demonstrate the value of satellite observations as a complement to in situ platforms such as voluntary observing ships and moored buoys. By combining satellite products from the Copernicus Marine Environmental Monitoring Service with in situ observations, it was possible to characterise the variability of pCO2,sw and pHT,is in the waters surrounding the Canary Islands and to quantify the regional air-sea CO2 flux.

Four modelling approaches, ranging from classical multivariate statistics to more sophisticated machine-learning techniques, were applied using atmospheric pCO2, SST, Chl a, and MLD as controlling variables. Multiple linear regression, neural network, and categorical boosting models yielded comparable results, with RMSE, MAE, and R2 values similar to those reported for oceanic-scale applications. Among all approaches, the bagging model provided the best performance, with RMSE values below 2.5 µatm (< 0.7 %) for pCO2,sw and 0.002 for pHT,is, R2 exceeding 0.99, and no significant differences relative to monthly mean observations.

Application of the bagging approach enabled a detailed description of the seasonal and longitudinal variability of pCO2,sw and pHT,is across the Canary region. After confirming agreement between in situ and satellite-derived SST within ±0.15 °C, the model was trained using measured xCO2,sw (converted to pCO2,sw) together with satellite SST, chlorophyll a and MLD, providing high-resolution spatial and temporal coverage. A persistent longitudinal SST gradient of ∼ 1 °C, driven by African coastal upwelling and offshore transport of upwelling filaments, resulted in systematically higher pCO2,sw and lower pHT,is values in the western sector (between El Hierro and Tenerife) compared with the eastern sector (between Tenerife and Lanzarote). In terms of air-sea CO2 exchange, the western region acted as a source throughout the study period, whereas the eastern region transitioned from a weak sink to a source after 2022. The increasing trend in SST across the Canary region, particularly during the anomalous warm year 2023 and during warmer winters in 2020, 2023 and 2024, is identified as the main driver of enhanced CO2 outgassing. Overall, the Canary region acted as a net CO2 source of 0.39 ± 0.17 mol m−2 yr−1 between 2019 and 2024, increasing from 0.9 Tg CO2 in 2019 to 4.5 Tg CO2 in 2024, with a maximum of 4.8 Tg CO2 in 2023. These results highlight the complexity of modelling pCO2,sw and pHT,is in coastal and island-influenced environments, where physical and biological is greater than in the open ocean. The pronounced influence of the 2023 marine heatwave, which persisted for more than one year, underscores the sensitivity of short time series to extreme events and reinforces the need for long-term observations when assessing interannual trends. Although model performance is robust, longer time series are required to better constrain long-term changes in pCO2,sw and pHT,is in the Canary Islands waters. Nevertheless, this study demonstrates that the integration of sustained observations, satellite data and machine-learning techniques provides a powerful framework for characterising regional air-sea CO2 exchange.

Underway observations from the SOOP CanOA-VOS programme in the Canary region, including buoys data for the period February 2019 to December 2024, used in this study, are openly available via Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16780085, Gonzalez-Davila and Santana-Casiano, 2025) and have been accessible since September 2023 through the ICOS Data Portal (https://www.icos-cp.eu/data-products/ocean-release, last access: 22 January 2026) under the CanOA-VOS-1 product. The model codes used to implement the different machine-learning approaches are also available in open access via Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16780313, Irene et al., 2025). All satellite datasets are available from the Copernicus Climate Data Store (https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/, last access: 22 January 2026). Atmospheric pCO2 data from the IZAÑA (IZO) station are available from the NOAA's Global Monitoring Laboratory at https://doi.org/10.15138/wkgj-f215 (Lan et al., 2025).

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/os-22-609-2026-supplement.

All authors made significant contributions to this research. MGD, JMSC, AGG and DGS installed and maintained the VOS and buoy instrumentation and led the study conceptualisation. Together with ISM and DCH, carried out data curation and formal analysis. ISM and DE developed analytical routines and applied machine-learning techniques to data processing. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript, review, editing and approved its submission.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

We thank the owner of the JONA SOPHIE, Reederei Stefan Patjens GmbH & Co. KG, as well as NISA-Marítima, the captains, and crew members for their support during this collaboration. We also thank the FRED OLSEN EXPRESS shipping company and its captains and crews for their assistance with all operations. Special thanks are extended to the technician Adrián Castro-Álamo for biweekly equipment maintenance and discrete sampling of total alkalinity aboard the vessel.

The SOOP CanOA-VOS line has been part of the Spanish contribution to the Integrated Carbon Observation System (ICOS-ERIC; https://www.icos-cp.eu/, last access: 22 January 2026) since 2021 and has been recognised as an ICOS Class 1 Ocean Station. D. C.-H. was supported by the PhD grant PIFULPGC-2020-2 ARTHUM-2. This work also received funding from the PLANCLIMAC2 project (1/MAC/2/2.4/0006) under the Interreg VI Madeira–Azores–Canarias (MAC) 2021–2027 Territorial Cooperation Programme, co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF).

This research was supported by the Canary Is20 lands Government and the Loro Parque Foundation through the CanBIO project, CanOA subproject (2019–2024), and the CARBOCAN agreement (Consejería de Transición Ecológica y Energía, Gobierno de Canarias). This work also received funding from the PLANCLIMAC2 project (1/MAC/2/2.4/0006) under the Interreg VI 25 Madeira–Azores–Canarias (MAC) 2021–2027 Territorial Cooperation Programme, co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF).

This paper was edited by Matthew P. Humphreys and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

AEMET: Centro de Investigación Atmosférica de Izaña, Medidas de CO2, https://gml.noaa.gov/aftp/data/trace_gases/co2/flask/surface/txt/co2_izo_surface-flask_1_ccgg_event.txt (last access: 26 May 2025), 2024.

Allen, R. G., Pereira, L. S., Raes, D., and Smith, M.: Crop evapotranspiration-Guidelines for computing crop water requirements-FAO Irrigation and drainage paper 56, Fao, Rome, ISBN 92-5-104219-5, 1998.

Bai, Y., Cai, W.-J., He, X., Zhai, W., Pan, D., Dai, M., and Yu, P.: A mechanistic semi- analytical method for remotely sensing sea surface pCO2 in river-dominated coastal oceans: A case study from the East China Sea, J. Geophys. Res. Ocean., 120, 2331–2349, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014JC010632, 2015.

Bange, H. W., Mongwe, P., Shutler, J. D., Arévalo-Martínez, D. L., Bianchi, D., Lauvset, S. K., Liu, C., Löscher, C. R., Martins, H., Rosentreter, J. A., Schmale, O., Steinhoff, T., Upstill-Goddard, R. C., Wanninkhof, R., Wilson, S. T., and Xie, H.: Advances in understanding of air–sea exchange and cycling of greenhouse gases in the upper ocean, Elem. Sci. Anth., 12, https://doi.org/10.1525/elementa.2023.00044, 2024.

Bates, N. R., Astor, Y. M., Church, M. J., Currie, K., Dore, J. E., González-Dávila, M., Lorenzoni, L., Muller-Karger, F., Olafsson, J., and Santana-Casiano, J. M.: A Time-Series View of Changing Surface Ocean Chemistry Due to Ocean Uptake of Anthropogenic CO2 and Ocean Acidification, Oceanography, 27, 126–141, https://doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2014.16, 2014.

Boehme, S. E., Sabine, C. L., and Reimers, C. E.: CO2 fluxes from a coastal transect: A time- series approach, Mar. Chem. 63, 49–67, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4203(98)00050-4, 1998.

Borges, A. V., Delille, B., and Frankignoulle, M.: Budgeting sinks and sources of CO2 in the coastal ocean: Diversity of ecosystem counts, Geophys. Res. Lett., 32, 1–4, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005GL023053, 2005.

Breiman, L.: Bagging predictors, Mach. Learn., 24, 123–140, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00058655, 1996.

Cai, W. J., Dai, M., and Wang, Y.: Air-sea exchange of carbon dioxide in ocean margins: A province-based synthesis, Geophys. Res. Lett., 33, 2–5, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006GL026219, 2006.

Cao, Z., Yang, W., Zhao, Y., Guo, X., Yin, Z., Du, C., Zhao, H., and Dai, M.: Diagnosis of CO2 dynamics and fluxes in global coastal oceans, Natl. Sci. Rev., 7, 786–797, https://doi.org/10.1093/nsr/nwz105, 2020.

Chen, S., Hu, C., Byrne, R. H., Robbins, L. L., and Yang, B.: Remote estimation of surface pCO2 on the West Florida Shelf, Cont. Shelf Res., 128, 10–25, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csr.2016.09.004, 2016.

Chen, S., Hu, C., Barnes, B. B., Wanninkhof, R., Cai, W. J., Barbero, L., and Pierrot, D.: A machine learning approach to estimate surface ocean pCO2 from satellite measurements, Remote Sens. Environ., 228, 203–226, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2019.04.019, 2019.

Curbelo-Hernández, D., González-Dávila, M., González, A. G., González-Santana, D., and Santana-Casiano, J. M.: CO2 fluxes in the Northeast Atlantic Ocean based on measurements from a surface ocean observation platform, Sci. Total Environ., 775, 145804, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145804, 2021.

Curbelo-Hernández, D., Santana Casiano, J. M., González González, A., González Santana, D., and González Dávila, M.: Air-Sea CO2 Exchange in the Strait of Gibraltar, Front. Mar. Sci., 8, 745304, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2021.745304, 2022.

Curbelo Hernández, D., Santana Casiano, J. M., González González, A., González Santana, D., and González Dávila, M.: Air-Sea CO2 Exchange in the Strait of Gibraltar, Front. Mar. Sc., 8, 745304, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2021.745304, 2022.

Dai, M., Su, J., Zhao, Y., Hofmann, E. E., Cao, Z., Cai, W.-J., Gan, J., Lacroix, F., Laurelle, G. G., Meng, F., Müller, J. D., Regnier, P. A. G., Wang, G., and Wang, Z.: Carbon fluxes in the coastal ocean: Synthesis, boundary processes and future trends. Annu. Rev. Earth Pl. Sci., 50, 593–626, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-earth-032320-090746, 2022.

Davenport, R., Neuer, S., Hernandez-Guerra, A., Rueda, M. J., Llinas, O., Fischer, G., and Wefer, G.: Seasonal and interannual pigment concentration in the Canary Islands region from CZCS data and comparison with observations from the ESTOC, Int. J. Remote Sens., 20, 1419–1433, https://doi.org/10.1080/014311699212803, 1999.

Dickson, A. G., Sabine, C. L., and Christian, J. R. (Eds.): Guide to best practices for ocean CO2 measurement. Sidney, British Columbia, North Pacific Marine Science Organization, PICES Special Publication 3, IOCCP Report 8, 191 pp., https://doi.org/10.25607/OBP-1342, 2007.

Doney, S. C., Fabry, V. J., Feely, R. A., and Kleypas, J. A.: Ocean acidification: The other CO2 problem, Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci., 1, 169–192, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.marine.010908.163834, 2009.

Dorogush, A. V., Ershov, V., and Gulin, A.: CatBoost: gradient boosting with categorical features support, ArXiv [preprint], https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1810.11363, 2018.

Duke, P. J., Hamme, R. C., Ianson, D., Landschützer, P., Swart, N. C., and Covert, P. A.: High-resolution neural network demonstrates strong CO2 source-sink juxtaposition in the coastal zone, J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans, 129, e2024JC021134, https://doi.org/10.1029/2024JC021134, 2024.

Fennel, K., Wilkin, J., Previdi, M., and Najjar, R.: Denitrification effects on air-sea CO2 flux in the coastal ocean: Simulations for the northwest North Atlantic, Geophys. Res. Lett., 35, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008GL036147, 2008.

Ford, D. J., Tilstone, G. H., Shutler, J. D., and Kitidis, V.: Derivation of seawater pCO2 from net community production identifies the South Atlantic Ocean as a CO2 source, Biogeosciences, 19, 93–115, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-19-93-2022, 2022.

Friedlingstein, P., O'Sullivan, M., Jones, M. W., Andrew, R. M., Hauck, J., Landschützer, P., Le Quéré, C., Li, H., Luijkx, I. T., Olsen, A., Peters, G. P., Peters, W., Pongratz, J., Schwingshackl, C., Sitch, S., Canadell, J. G., Ciais, P., Jackson, R. B., Alin, S. R., Arneth, A., Arora, V., Bates, N. R., Becker, M., Bellouin, N., Berghoff, C. F., Bittig, H. C., Bopp, L., Cadule, P., Campbell, K., Chamberlain, M. A., Chandra, N., Chevallier, F., Chini, L. P., Colligan, T., Decayeux, J., Djeutchouang, L. M., Dou, X., Duran Rojas, C., Enyo, K., Evans, W., Fay, A. R., Feely, R. A., Ford, D. J., Foster, A., Gasser, T., Gehlen, M., Gkritzalis, T., Grassi, G., Gregor, L., Gruber, N., Gürses, Ö., Harris, I., Hefner, M., Heinke, J., Hurtt, G. C., Iida, Y., Ilyina, T., Jacobson, A. R., Jain, A. K., Jarníková, T., Jersild, A., Jiang, F., Jin, Z., Kato, E., Keeling, R. F., Klein Goldewijk, K., Knauer, J., Korsbakken, J. I., Lan, X., Lauvset, S. K., Lefèvre, N., Liu, Z., Liu, J., Ma, L., Maksyutov, S., Marland, G., Mayot, N., McGuire, P. C., Metzl, N., Monacci, N. M., Morgan, E. J., Nakaoka, S.-I., Neill, C., Niwa, Y., Nützel, T., Olivier, L., Ono, T., Palmer, P. I., Pierrot, D., Qin, Z., Resplandy, L., Roobaert, A., Rosan, T. M., Rödenbeck, C., Schwinger, J., Smallman, T. L., Smith, S. M., Sospedra-Alfonso, R., Steinhoff, T., Sun, Q., Sutton, A. J., Séférian, R., Takao, S., Tatebe, H., Tian, H., Tilbrook, B., Torres, O., Tourigny, E., Tsujino, H., Tubiello, F., van der Werf, G., Wanninkhof, R., Wang, X., Yang, D., Yang, X., Yu, Z., Yuan, W., Yue, X., Zaehle, S., Zeng, N., and Zeng, J.: Global Carbon Budget 2024, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 17, 965–1039, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-17-965-2025, 2025.

Friedrich, T. and Oschlies, A.: Neural network-based estimates of North Atlantic surface pCO2 from satellite data: A methodological study, J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans, 114, https://doi.org/10.1029/2007JC004646, 2009.

Frölicher, T. L. and Laufkötter, C.: Emerging risks from marine heat waves, Nat. Commun., 9, 650, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-03163-6, 2018.

Gattuso, J. P., Frankignoulle, M., and Wollast, R.: Carbon and carbonate metabolism in coastal aquatic ecosystems, Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst., 29, 405–434, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.29.1.405, 1998.

González, A. G., Aldrich-Rodríguez, A., González-Santana, D., González-Dávila, M., and Santana-Casiano, J. M.: Seasonal variability of coastal pH and CO2 using an oceanographic buoy in the Canary Islands, Frontiers in Marine Science, 11, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2024.1337929, 2024.

González-Dávila, M. and Santana-Casiano, J. M.: Long-term trends of pH and inorganic carbon in the Eastern North Atlantic: the ESTOC site, Front. Mar. Sci., 10, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2023.1236214, 2023.

Gonzalez-Davila, M. and Santana-Casiano, J. M.: Canary Islands pCO2/pH data from 2019 to 2024 using VOS and Buoys data, Zenodo [data set], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16780085, 2025.

González-Dávila, M., Santana-Casiano, J. M., Rueda, M. J., Llinás, O., and González-Dávila, E. F.: Seasonal and interannual variability of sea-surface carbon dioxide species at the European Station for time series in the Ocean at the Canary Islands (ESTOC) between 1996 and 2000, Glob. Biogeochem. Cy., 17, https://doi.org/10.1029/2002gb001993, 2003.

González-Dávila, M., Santana-Casiano, J. M., Rueda, M. J., and Llinás, O.: The water column distribution of carbonate system variables at the ESTOC site from 1995 to 2004, Biogeosciences, 7, 3067–3081, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-7-3067-2010, 2010.

Gregor, L., Shutler, J., and Gruber, N.: High-Resolution Variability of the Ocean Carbon Sink, Glob. Biogeochem. Cy., 38, https://doi.org/10.1029/2024GB008127, 2024.

Gruber, N., Keeling, C. D., and Bates, N. R.: Interannual variability in the North Atlantic ocean carbon sink, Science, 298, 2374–2378, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1077077, 2002.

Hobday, A. J., Alexander, L. V., Perkins, S. E., Smale, D. A., Straub, S. C., Oliver, E. C., and Wernberg, T.: A hierarchical approach to defining marine heatwaves. Prog. Oceanogr., 141, 227-238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pocean.2015.12.014, 2016.

Holbrook, N. J., Scannell, H. A., Sen Gupta, A., Benthuysen, J. A., Feng, M., Oliver, E. C., and Wernberg, T.: A global assessment of marine heatwaves and their drivers, Nat. Commun., 10, 2624, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10206-z, 2019.

Ikawa, H., Faloona, I., Kochendorfer, J., Paw U, K. T., and Oechel, W. C.: Air–sea exchange of CO2 at a Northern California coastal site along the California Current upwelling system, Biogeosciences, 10, 4419–4432, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-10-4419-2013, 2013.

Irene, S.-M., Gonzalez-Davila, M., and Santana Casiano, J. M.: Models for predicting the partial pressure of CO2 in seawater (pCO2,sw) using different machine Learning approaches, Zenodo [code], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16780313, 2025.

Jo, Y.-H., Dai, M., Zhai, W., Yan, X.-H., and Shang, S.: On the variations of sea surface pCO2 in the northern South China Sea: A remote sensing based neural network approach, J. Geophys. Res., 117, C08022, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011JC007745, 2012-

Laruelle, G. G., Lauerwald, R., Pfeil, B., and Regnier, P.: Regionalized global budget of the CO2 exchange at the air-water interface in continental shelf seas, Global Biogeochem. Cy., 1199–1214, https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.13280, 2014.

Lan, X., Petron, G., Baugh, K., Crotwell, A. M., Crotwell, M. J., DeVogel, S., Madronich, M., Mauss, J., Mefford, T., Moglia, E., Morris, S., Mund, J. W., Searle, A., Thoning, K. W., Wolter, S., and Miller, J.: Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide Dry Air Mole Fractions from the NOAA GML Global Greenhouse Gas Reference Network, Version: 2025-08-15, Carbon Cycle Cooperative Global Air Sampling Network: 1967–Present [data set], https://doi.org/10.15138/wkgj-f215, 2025.

Landschützer, P., Gruber, N., Bakker, D. C. E., and Schuster, U.: Recent variability of the global ocean carbon sink, Global Biogeochem. Cy., 28, 927–949. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014GB004853, 2014.

Lefèvre, N. and Taylor, A.: Estimating pCO2 from sea surface temperatures in the Atlantic gyres, Deep-Sea Res. Pt. I, 49, 539–554, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0967-0637(01)00064-4, 2002.

Le Quéré, C., Raupach, M. R., Canadell, J. G., Marland, G., Bopp, L., Ciais, P., Conway, T. J., Doney, S. C., Feely, R. A., Foster, P., Friedlingstein, P., Gurney, K., Houghton, R. A., House, J. I., Huntingford, C., Levy, P. E., Lomas, M. R., Majkut, J., Metzl, N., Ometto, J. P., Peters, G. P., Prentice, I. C., Randerson, J. T., Running, S. W., Sarmiento, J. L., Schuster, U., Sitch, S., Takahashi, T., Viovy, N., Van Der Werf, G. R., and Woodward, F. I.: Trends in the sources and sinks of carbon dioxide, Nat. Geosci., 2, 831–836, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo689, 2009.

Lohrenz, S. E., Cai, W.-J., Chakraborty, S., Huang, W.-J., Guo, X., He, R., Xue, Z., Fennel, K., Howden, S., and Tian, H.: Satellite estimation of coastal pCO2 and air-sea flux of carbon dioxide in the northern Gulf of Mexico, Remote Sens. Environ., 207, 71–83, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2017.12.039, 2018.

Lueker, T. J., Dickson, A. G., and Keeling, C. D.: Ocean pCO2 calculated from dissolved inorganic carbon, alkalinity, and equations for K1 and K2: Validation based on laboratory measurements of CO2 in gas and seawater at equilibrium, Mar. Chem., 70, 105–119, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4203(00)00022-0, 2000.

Mintrop, L., Pérez, F. F., González-Dávila, M., Santana-Casiano, J. M., and Körtzinger, A.: Alkalinity determination by potentiometry: intercalibration using three different methods, Ciencias Mar., 26, 23–27, https://doi.org/10.7773/cm.v26i1.573, 2000.

Pelegrí, J. L., Arístegui, J., Cana, L., González-Dávila, M., Hernández-Guerra, A., Hernández-León, S., Marrero-Díaz, A., Montero, M. F., Sangrá, P., and Santana-Casiano, M.: Coupling between the open ocean and the coastal upwelling region off northwest Africa: water recirculation and offshore pumping of organic matter, J. Mar. Syst., 54 (1–4), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmarsys.2004.07.003, 2005.

Pelegrí, J. L., Csanady, G. T., and Martins, A.: The north Atlantic nutrient stream, Journal of Oceanography, 52, 275–299, 1996.

Pierrot, D., Neill, C., Sullivan, K., Castle, R., Wanninkhof, R., Lüger, H., Johannessen, T., Olsen, A., Feely, R. A., and Cosca, C. E.: Recommendations for autonomous underway pCO2 measuring systems and data-reduction routines, Deep-Sea Res. Pt. II, 56, 512–522, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2008.12.005, 2009.

Qian, L., Chen, Z., Huang, Y., and Stanford, R. J.: Employing categorical boosting (CatBoost) and meta-heuristic algorithms for predicting the urban gas consumption, Urban Climate, 51, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uclim.2023.101647, 2023.

Prokhorenkova, L., Gusev, G., Vorobev, A., Dorogush, A. V., and Gulin, A.: CatBoost: unbiased boosting with categorical features, 32nd Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2018), Montréal, Canada, https://github.com/catboost/catboost (last access: 23 January 2026), 2018.

Regnier, P., Resplandy, L., Najjar, R. G., and Ciais, P.: The land-to-ocean loops of the global carbon cycle, Nature, 603, 401–410, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04339-9, 2022.

R Core Team: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, https://www.r-project.org/ (last access: 23 January 2026), 2019.

Resplandy, L., Hogikyan, A., Müller, J. D., Najjar, R. G., Bange, H. W., Bianchi, D., Weber, T., Cia, W.-J., Doney, S. C., Fennel, K., Gehlen, M., Hauck, J., Lacroix, F., Landschützer, P., Le Quéré, C., Roobaert, A., Schwinger, J., Berthet, S., Bopp, L., Chau, T. T. T., Dai, M., Gruber, N., Ilyina, T., Kock, A., Manizza, M., Lachkar, Z., Laurelle, G. G., Liao, E., Lima, E. D., Nissen, C., Rödenbeck, C., Séférian, R., Toyama, K., Tsujino, H., and Regnier, P.: A synthesis of global coastal ocean greenhouse gas fluxes, Glob. Biogeochem. Cy., 38, e2023GB007803, https://doi.org/10.1029/2023GB007803, 2024.

Roobaert, A., Laruelle, G. G., Landschützer, P., Gruber, N., Chou, L., and Regnier, P.: The spatiotemporal dynamics of the sources and sinks of CO2 in the global coastal ocean, Global Biogeochem. Cy., 33, 1693–1714, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GB006239, 2019.

Roobaert, A., Resplandy, L., Laruelle, G. G., Liao, E., and Regnier, P.: Unraveling the physical and biological controls of the global coastal CO2 sink, Global Biogeochem. Cy., 38, e2023GB007799, https://doi.org/10.1029/2023GB007799, 2024.

Santana-Casiano, J. M., González-Dávila, M., Laglera-Baquer, L. M., and Rodríguez-Somoza, M. J.: Carbon dioxide system in the Canary region during October 1995, Sci. Mar., 65, 41–49, https://doi.org/10.3989/scimar.2001.65s141, 2001.

Santana-Casiano, J. M., González-Dávila, M., Rueda, M. J., Llinás, O., and González-Dávila, E. F.: The interannual variability of oceanic CO2 parameters in the northeast Atlantic subtropical gyre at the ESTOC site, Global Biogeochem. Cy., 21, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006GB002788, 2007.

Santana-Casiano, J. M., González-Dávila, M., Laglera-Baquer, L. M., and Rodríguez-Somoza, M. J.: Carbon dioxide system in the Canary region during October 1995, Sci. Mar., 65, 41–49, https://doi.org/10.3989/scimar.2001.65s141, 2021.

Sarmiento, J., Gruber, N., and McElroy, M.: Ocean Biogeochemical Dynamics, Phys. Today, 60, 65, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2754608, 2007.

Schlitzer, R.: Ocean data view, https://odv.awi.de (last access: 10 July 2025) 2022.

Shadwick, E. H., Thomas, H., Comeau, A., Craig, S. E., Hunt, C. W., and Salisbury, J. E.: Air-Sea CO2 fluxes on the Scotian Shelf: seasonal to multi-annual variability, Biogeosciences, 7, 3851–3867, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-7-3851-2010, 2010.

Siegenthaler, U. and Sarmiento, J. L.: Atmospheric carbon dioxide and the ocean, Nature 399, 119–125, https://doi.org/10.1038/340301a0, 1993.

Signorini, S. R., Mannino, A., Najjar Jr., R. G., Friedrichs, M. A. M., Cai, W.-J., Salisbury, J., Wang, Z. A., Thomas, H., and Shadwick, E.: Surface ocean pCO2 seasonality and sea-air CO2 flux estimates for the North American east coast, J. Geophys. Res. Ocean, 118, 5439–5460. https://doi.org/10.1002/jgrc.20369, 2013.

Sun, H., He, Y., Chen., Y., and Zhao, B.: Space-Time Sea Surface pCO2 estimation in the North Atlantic based on CatBoost, Remote Sens., 13, 2805, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs13142805, 2021.

Takahashi, T., Olafsson, J., Goddard, J. G., Chipman, D. W., and Sutherland, S. C.: Seasonal variation of CO2 and nutrients in the high-latitude surface oceans: A comparative study, Global Biogeochem. Cy., 7, 843–878, https://doi.org/10.1029/93GB02263, 1993.

Takahashi, T., Sutherland, S. C., Sweeney, C., Poisson, A., Metzl, N., Tilbrook, B., Bates, N., Wannikhof, R., Feely, R. A., Sabine, C., Olafsson, J., and Nojiri, Y.: Global air-sea flux of CO2 based on surface ocean pCO2, and seasonal biological and temperature effects, Deep. Res. II, 49, 1601–1622, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0967-0645(02)00003-6, 2002.

Takahashi, T., Sutherland, S. C., Wanninkhof, R., Sweeney, C., Feely, R. A., Chipman, D. W., Hales, B., Friederich, G., Chavez, F., Sabine, C., Watson, A., Bakker, D. C. E., Schuster, U., Metzl, N., Yoshikawa-Inoue, H., Ishii, M., Midorikawa, T., Nojiri, Y., Körtzinger, A., Steinhoff, T., Hoppema, M., Olafsson, J., Arnarson, T. S., Tilbrook, B., Johannessen, T., Olsen, A., Bellerby, R., Wong, C. S., Delille, B., Bates, N. R., and de Baar, H. J. W.: Climatological mean and decadal change in surface ocean pCO2, and net sea-air CO2 flux over the global oceans, Deep. Res. II, 56, 554–577, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2008.12.009, 2009.