the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Diel variability affects the inorganic carbon system in the sea-surface microlayer and influences air-sea CO2 flux estimates

Ander López-Puertas

Oliver Wurl

Sanja Frka

Mariana Ribas-Ribas

The ocean plays a crucial role in the global carbon cycle by absorbing and storing about one-third of anthropogenic carbon dioxide (CO2). It is estimated that the ocean has sequestered approximately 26 % of CO2 emissions over the last decade, resulting in significant changes in the marine carbon system and impacting the marine environment. The sea-surface microlayer (SML) plays a crucial role in these processes, facilitating the transfer of matter and energy between the ocean and the atmosphere. However, most studies on the carbon cycle in the SML have primarily addressed daily variability and overlooked nocturnal processes, which may lead to inaccurate global carbon estimates. We analysed temperature, salinity, pHT25, and pCO2 using data collected over three complete diel cycles during an oceanographic campaign along the Croatian coast near Šibenik in the Middle Adriatic. Our analysis revealed statistically significant differences (p<0.05) between daytime and nighttime measurements of temperature, salinity, and pHT25. Diel differences in pCO2, were also observed, with patterns largely driven by temperature effects and short-term mixing. These differences may be related to the occurrence of buoyancy fluxes, which are typically more pronounced during the day and could enhance CO2 fluxes, as observed with values of 1.98 ± 2.52 mmol cm−2 h−1 during the day, while at night, they dropped to 0.01 ± 0.02 mmol cm−2 h−1. These findings emphasise the importance of considering complete diurnal cycles to accurately capture the variability in thermohaline features and carbon exchange processes, thereby improving our understanding of the ocean's role in climate change.

- Article

(3822 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(682 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

The ocean is a crucial climate regulator that mitigates the effects of anthropogenic emissions (Gattuso et al., 2015). It absorbs more than 90 % of the Earth's excess heat (Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2014; Pörtner et al., 2019) and captures approximately one-third of anthropogenic carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions (Pörtner et al., 2019; Wong et al., 2014). It is well known that CO2 has a significant impact on seawater chemistry (Doney et al., 2009; Gattuso et al., 2015). It is estimated that the ocean has sequestered approximately 26 % of global CO2 emissions over the last decade (Friedlingstein et al., 2025). Consequently, changes in the ocean environment have exceeded the magnitude and rate of natural variation due to anthropogenic carbon perturbation over the last millennia (Gattuso et al., 2015). In this context, the marine carbon system undergoes substantial modifications, resulting in various effects on the marine environment, including a decrease in pH levels (Doney et al., 2009; IPCC, 2023; Orr et al., 2005). Therefore, understanding the evolving state of marine biogeochemistry in the context of climate change is crucial, with a primary focus on the upper layers of the water column, which are closely linked to ocean-atmosphere interactions.

In the ocean-atmosphere system, the sea-surface microlayer (SML) plays a vital role in transferring materials and energy, such as heat, gases, and particles (Wurl et al., 2019), which must pass through it (Frka et al., 2009; Stolle et al., 2020). The SML is a distinctive and complex marine environment that represents the interfacial boundary layer between the ocean and the atmosphere (Cunliffe et al., 2013; Stolle et al., 2020; Wurl et al., 2011). Its thickness typically does not exceed 1000 µm, and it exhibits distinct biological and physicochemical properties compared with the underlying water masses (Cunliffe et al., 2013; Stolle et al., 2020; Wurl et al., 2011). Thus, the SML experiences instantaneous meteorological forcing, such as solar radiation, wind, and atmospheric inputs (Gassen et al., 2023; Wurl et al., 2019), which impacts the development of physical and biogeochemical processes occurring in the underlying water (Engel et al., 2017; Stolle et al., 2020; Wurl et al., 2017). These characteristics of the SML overlap with the growing interest in oceanographic research to study the spatiotemporal variability of the marine carbon system (Cantoni et al., 2016), as this layer is essential for understanding global marine biogeochemistry. However, to gain a comprehensive spatiotemporal perspective on marine carbon chemistry processes, focusing on underexplored fields, such as the role of nocturnal processes within the diel cycle, is crucial.

Daily variations force cyclic changes in chemistry (De Montety et al., 2011), which are influenced by processes such as photosynthesis, air-sea gas exchange, and various environmental conditions (e.g., light, temperature, and nutrient availability) (Poulson and Sullivan, 2010). These processes directly affect the seawater pH by adding or removing CO2 from seawater (Poulson and Sullivan, 2010; Takahashi et al., 2002). It is well known that photosynthesis consumes CO2 during the day, thereby reducing pCO2 levels and consequently causing an increase in pH (Cantoni et al., 2012; Takahashi et al., 2002). At night, the CO2 produced by respiration tends to be more constant and accumulates in the water column, leading to an increase in pCO2 and a decrease in pH (Cantoni et al., 2012; del Giorgio and Williams, 2005; Gattuso et al., 1999; Shaw et al., 2012). Although these processes are significant for seawater chemistry, research has predominantly focused on diurnal processes. As a result, the roles of respiration and other nocturnal processes in the SML remain largely unexplored (Yates et al., 2007).

Within this framework, the Mediterranean Sea presents a unique research opportunity to investigate the spatiotemporal variability of the marine carbon system. It is often referred to as a “laboratory basin” (Bergamasco and Malanotte-Rizzoli, 2010; Robinson and Golnaraghi, 1994) because it enables us to approximate processes occurring on a global scale within a shorter timeframe and smaller space (Álvarez et al., 2014). Despite representing 0.8 % of the global ocean surface (Álvarez-Rodríguez, 2012), the Mediterranean Sea is considered an important anthropogenic carbon storage (Álvarez et al., 2014), as it absorbs a disproportionally larger amount of anthropogenic carbon compared to the global ocean (Hassoun et al., 2015; Schneider et al., 2010). Higher acidification ranges (−0.001 to −0.009 pH unit yr−1) (Hassoun et al., 2022) were measured and exceeded those measured in the Atlantic Ocean (−0.001 to −0.0026 pH unit yr−1) (Takahashi et al., 2014), in line with regional coastal studies showing strong acidification trends in the Mediterranean (Kapsenberg et al., 2017). However, as explored in this study, the dynamics of biogeochemical processes in coastal regions are more complex than those in the open ocean (Borges, 2005). When examining oceanic regions, it is essential to recognise that daily variability has a profound impact on marine carbon chemistry.

This study emphasises the role of diel variability in thermohaline features and dynamics of the marine inorganic carbon cycle in the coastal region of the Mediterranean Sea (Šibenik, Croatia), thereby providing a comprehensive understanding of the processes that influence the complete diurnal cycle. Therefore, it is essential to incorporate nocturnal processes into global estimates of marine carbon cycle dynamics. We present high-resolution data to understand biogeochemical processes and their variability in the water column, which complicates predictions of variations in the coastal marine carbon system (Cantoni et al., 2012). We have focused on understanding the nocturnal processes that affect the inorganic carbon system, thereby helping to clarify the uncertainties associated with this system. This study contributes to the identification of anthropogenic influences on the marine environment in the context of climate change.

2.1 Sampling Strategy and Seawater Analyses

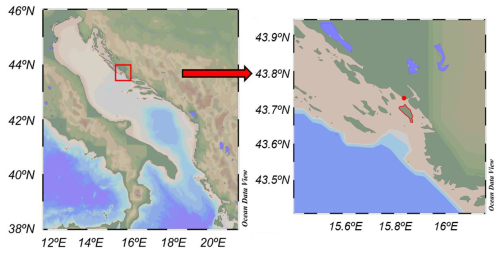

Sampling was conducted in the lower estuary of the Krka River (central-eastern Adriatic), offshore in the St. Anthony Channel, near Šibenik (Fig. 1). The estuary is highly stratified and exhibits microtidality, extending approximately 23 km inland, with depths increasing from less than 2 m at the head to around 42 m at the mouth (Cukrov et al., 2024a; Prohić and Juračić, 1989). Similar to other Mediterranean estuaries, tidal ranges are small (0.2–0.5 m), resulting in minimal currents and stable vertical stratification, with freshwater or brackish water flowing over a lower marine layer (Cukrov et al., 2024a). Average annual river discharge is ∼ 50 m3 s−1, varying seasonally from ∼ 5 to 480 m s−1 (Bužančić et al., 2016; Cukrov et al., 2024b; Marcinek et al., 2020). Previous studies in the area have reported that water residence times range from a few days in winter to several weeks in summer, depending on the hydrodynamics of the freshwater or marine layers (Cetinić et al., 2006; Zutic and Legovic, 1987). During the sampling period (10–15 August 2020), precipitation was very low, averaging 1.4 mm d−1 during the days preceding the campaign (Croatian Meteorological and Hydrological Service, 2020), consistent with the dry summer conditions typical for the region. This environment provided ideal stable conditions for assessing the daily variability of SML and ULW parameters with minimal interference from tides or precipitation.

Figure 1Map of the sampling area in the Middle Adriatic Sea, created using Ocean Data View (Schlitzer, 2022). The red dot indicates the sampling area, whereas Zlarin Island, where the meteorological station is situated, is outlined in red.

Temperature, conductivity, and pH data from the SML were collected using sensors integrated in a flow-through system on the “Sea Surface Scanner (S3)” (Ribas-Ribas et al., 2017). The S3 is a 4.5 m long and 2.2 m wide uncrewed catamaran, remotely piloted by radio control from a small support vessel (a Zodiac). As specified in Ribas-Ribas et al. (2017), the system features rotating glass discs on which the SML water adheres via surface tension. A set of scraping mechanisms on the immersed side collects the adhering water and transfers it to a closed, continuous-flow system, minimising atmospheric contact. Underlaying water (ULW) was continuously collected at a depth of 1 m through a rigid inlet pipe. Both SML and ULW water were pumped directly to two independent packages of onboard sensors (Table 1) and sampler systems, each equipped with its own temperature, conductivity/salinity, and pH sensors, allowing simultaneous measurements to be taken in both layers. In addition, the S3 carried an automated water collector (Table 1) with twenty-four 1 L polypropylene bottles, which could be filled remotely with SML or ULW water, allowing discrete samples to be collected during transects. Discrete samples for inorganic carbon parameters (DIC and TA) were collected in bottles (250 mL) directly from the S3 outlets at each sampling event, with one sample per parameter and depth, approached by the catamaran with the support vessel, and immediately sealed to prevent atmospheric contamination.

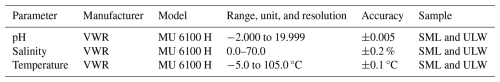

Table 1Manufacturers, models, and specifications of the sensors employed to measure pH, salinity, and temperature in the sea-surface microlayer (SML) and underlying water (ULW). Adapted from Ribas-Ribas et al. (2017).

Sensors recorded temperature, conductivity, and pH from both SML and ULW at 30 s intervals. Specifically, the pH was measured using the integrated sensor of the S3 flow-through system (Ribas-Ribas et al., 2017) and is reported on the total scale. The uncertainties of the measured temperature, conductivity and pH were estimated based on sensor specifications (Table 1). Solar radiance and wind data were collected from a meteorological station (Davis Instruments, Vantage Pro2 Plus) located on Zlarin Island. Furthermore, subsamples from the SML and ULW water collected by the S3 system were stored in high-density polyethylene (HDPE) bottles to determine the phosphate (PO) and silicate [Si(OH)4] concentrations. To preserve the samples, mercury chloride (HgCl2) was added. The preserved samples were stored at +4 °C until further analysis in the laboratory. Nutrient concentrations were measured using a sequential automatic analyser (SAA, SYSTEA EASYCHEM) according to the standard protocols described by Laskov et al. (2007) and Fanning and Pilson (1973). These nutrient data were subsequently used as inputs for calculating partial pressure of CO2 (pCO2) with the CO2Sys program (Version v3.2.0, MATLAB) (Sharp et al., 2020; Van Heuven et al., 2011).

Field deployments of the S3 were conducted six times per diel cycle between 10 and 15 August 2020, with each deployment lasting 30–45 min. Although the catamaran moved along short transects within the sampling area, for analytical purposes, the sampling location was treated as a single point. The catamaran remained within a small area (maximum horizontal displacement ∼ 90 m based on GPS positions), and consequently, no significant horizontal gradients were expected at this spatial scale, since spatial variations within the region were minimal. For the analysis, a total of three diurnal cycles were sampled. In each cycle, four deployments were conducted during daytime conditions (diurnal data), and two deployments were performed at night (nocturnal data). Environmental conditions during the campaign were typical for the region, with no significant rainfall events. This deployment strategy enabled representative sampling of the study area while minimising the potential influence of microtidal variations (Fig. S1 in the Supplement) on the SML and ULW measurements.

2.2 Marine Carbon System Determination

DIC samples (20 mL) were analysed by coulometric titration (CM 5014, UIC, USA) with an excess of 10 % phosphoric acid. Total Alkalinity (TA) samples (100 mL) were measured via potentiometric titration (916 Ti-Touch, Metrohm, Switzerland) and calculated using a modified Gran plot approach implemented in Calkulate (version 1.8.0) (Humphreys et al., 2022). Calibration was performed with certified reference material (Batch 187) obtained from A. G. Dickson at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. The 1σ measurement precision was ±3 µmol kg−1 for DIC and ±2 µmol kg−1 for TA.

To eliminate the effects of temperature variation on the results, the pH values measured in the seawater samples were adjusted to the average temperature value of 25.43 °C, hereafter referred to as pHT25. The normalisation utilised an adjustment factor of 0.018 pH units per °C, which is widely accepted for the range of pH and TA conditions typical of seawater (Eq. 1) (Dickson et al., 2007; Dickson and Millero, 1987; Zeebe and Wolf-Gladrow, 2001):

To evaluate the marine carbon system, pCO2 was calculated with the CO2SYS program (Version v3.2.0, MATLAB) (Sharp et al., 2020; Van Heuven et al., 2011) using as input parameters: DIC; TA, PO, and Si(OH)4; salinity (S); temperature (T), and pressure. The respective dissociation constants were used for carbon (Mehrbach et al., 1973), sulfate (KSO4) (Dickson and Millero, 1987), fluorine (KF) (Perez and Fraga, 1987), and the borate-salinity ratio (Lee et al., 2010). Missing pCO2 values were due to erroneous DIC and/or TA measurements. Consequently, standard deviations could not be calculated when the number of reliable data points was less than three. Once the pCO2 values were calculated, the CO2 flux through the ocean-atmosphere interface in the monitoring area was estimated using the following equation:

where F is the CO2 flux (mmol m−2 d−1), ΔpCO2 is equal to the difference in the partial pressures of the gas between the surface water and the atmosphere, k is the gas transfer coefficient (cm h−1) from Wanninkhof, (2014), and α is the solubility of CO2 in seawater (mol L−1 atm−1). To calculate the partial pressure gradient of CO2, atmospheric pCO2 data were obtained as the monthly mean for August 2020 from the ICOS Lampedusa atmospheric station, which provides quality-controlled dry-air CO2 measurements representative of the Mediterranean region (Pecci et al., 2023). To quantify the bias introduced when nocturnal fluxes were ignored, we compared daily means including all valid data from each cycle with means based only on daytime measurements. The percentage error was defined as , with both means calculated as arithmetic averages of available fluxes. This approach explicitly evaluates the uncertainty in daily estimates when nocturnal processes are excluded (Garbe et al., 2014).

2.3 Salinity and density correction

To ensure high-quality data, a correction factor (CF) was applied to the continuous salinity and pHT25 data. Discrete salinity values obtained from laboratory analyses served as reference points and were compared to the average continuous values recorded by the S3 (Ribas-Ribas et al., 2017). This process resulted in the derivation of distinct CFs, which were applied at each depth and during each time interval of the S3 measurements (Ribas-Ribas et al., 2017). Once the salinity values were corrected, the pH was calculated using the CO2Sys program (Version v3.2.0, MATLAB) (Sharp et al., 2020; Van Heuven et al., 2011). These calculated pHT25 values were then utilised as reference points for comparison with the average continuous values obtained from the S3 measurements (Ribas-Ribas et al., 2017). After correcting for salinity, the density (ρ) was calculated using the TEOS-10 (https://www.teos-10.org/index.htm, last access: 12 February 2025) equation of state in RStudio (RStudio Team, 2023) based on the observed temperature and salinity values. From this calculation, sigma-t was defined as the density at a given temperature and salinity minus 1000 kg m−3. The propagated uncertainties for sigma-t and pCO2 were constrained by the measurement precisions of temperature (±0.1 °C), salinity (±0.2 %), pH (±0.005), together with the analytical reproducibility of DIC, and TA. These estimates provide a quantitative basis for evaluating the reliability of calculated variables in subsequent analyses.

2.4 Evaporation rate calculation

The evaporation rate (E) was estimated using the following formula, which relates the latent heat flux (QE) (Brutsaert, 2013), the latent heat of vaporisation (Lv) (Kittel and Kroemer, 1980), and the calculated density of seawater (ρ):

2.5 Statistical Analysis

Since the assumptions of normality and homoscedasticity were not met for the collected data, the Kruskal–Wallis test was chosen as a nonparametric alternative to ANOVA. This test revealed significant differences between the data collected during the day and night, as well as between the SML and ULW, and among the medians of the cycles studied. A significance level (α) of 0.05 was established to determine whether the groups differed significantly. All statistical analyses were performed using RStudio (RStudio Team, 2023). In addition, to carry out a complete analysis of the variability of the marine carbon system during the study period, anomalies in temperature, salinity, pHT25, and pCO2 data were calculated using the following expression: Δ(SML – ULW). These differences were calculated for diurnal and nocturnal data for each cycle.

The primary objective of this study was to understand the typical patterns of diurnal variability and depth-related differences in marine biogeochemistry during the observed cycles. Data on temperature, salinity, pHT25, and pCO2 were used to perform a statistical analysis of the similarity between the data collected during the diel cycle and to calculate the differences between the values measured in the SML and ULW. Additionally, we examined the temporal distribution using box-and-whisker plots and calculated the air-sea CO2 exchange across the SML.

3.1 Meteorological conditions

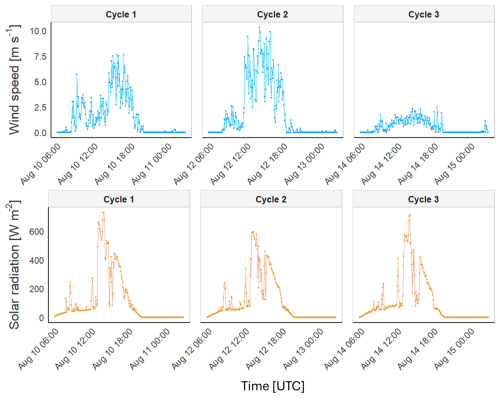

To study the potential variance in the meteorological forcing observed during the observations, time-series graphs were plotted for solar radiation and wind speed (Fig. 2). A consistent pattern of solar radiation was observed during all three cycles, with peaks of 525, 404, and 420 W m−2 observed at 14:00 UTC. Relatively low wind speeds were recorded during the day in all three cycles, averaging 1.26 ± 1.46 m s−1. Maximum wind speeds were observed at 14:00 and 18:00 UTC, higher for Cycles 1 and 2 (2.14 and 5.22 m s−1) than during Cycle 3 (0.95 m s−1). Additionally, a decrease in wind speed was observed throughout the night, approaching near-zero values, except during Cycle 3, when the wind speed remained consistently close to zero.

3.2 Daily trends

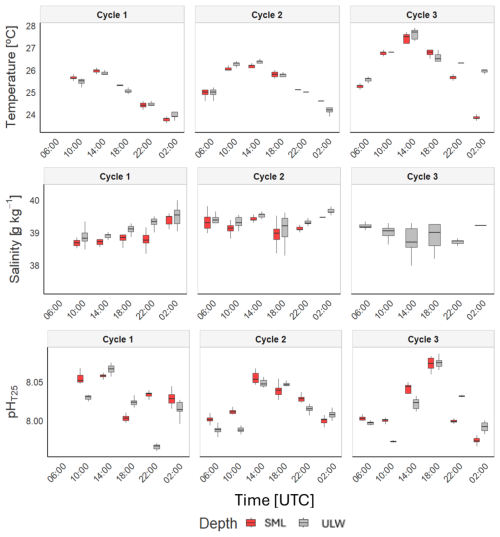

To investigate the overall distribution of physicochemical parameters throughout the daily sampling period at the SML and ULW, we show box-and-whisker plots for temperature, salinity, and pHT25 across different time intervals (Fig. 3). We also performed the Kruskal-Wallis test to determine statistically significant differences (see Sect. 2.5, Materials and Methods) between the SML and ULW (Table S1). The analysis revealed no significant temperature differences between the two depths during Cycle 1 (SML: 25.00 ± 0.85 °C; ULW: 24.90 ± 0.72 °C) and Cycle 2 (SML: 25.40 ± 0.62 °C; ULW: 25.40 ± 0.83 °C). However, in Cycle 3, ULW was slightly warmer, with a mean temperature of 26.60 ± 0.72 °C compared to 26.20 ± 1.20 °C in the SML. For salinity, significant differences were detected between SML and ULW during Cycles 1 and 2, with ULW exhibiting higher salinity levels in Cycle 1 (SML: 38.90 ± 0.32 g kg−1; ULW: 39.10 ± 0.32 g kg−1) and in Cycle 2 (SML: 39.2 ± 0.27 g kg−1; ULW: 39.4 ± 0.29 g kg−1). Notably, the salinity data showed greater variability, especially in Cycle 2, in the SML, whereas the ULW remained relatively constant. The pHT25 data collected over the three cycles displayed considerable variability, with fluctuations observed throughout the day. The SML and ULW data showed significant differences during the first two cycles, with slightly higher values in the SML for Cycle 1 (SML: 8.030 ± 0.020; ULW: 8.020 ± 0.033) and for Cycle 2 (SML: 8.020 ± 0.020; ULW: 8.010 ± 0.024). No significant differences were observed in Cycle 3 (SML: 8.020 ± 0.032; ULW: 8.020 ± 0.032).

Figure 3Box-and-whisker plots for the different time steps at which measurements were obtained at both the SML and ULW for temperature, salinity, and pHT25. Each boxplot represents all measurements obtained during a single 30–45 min deployment (data collected at 30 s intervals), with four daytime and two nighttime deployments per cycle. The horizontal line within each box denotes the mean of the data, whereas the vertical line associated with each box represents the 25th and 75th percentiles (Q1 and Q3) of the data.

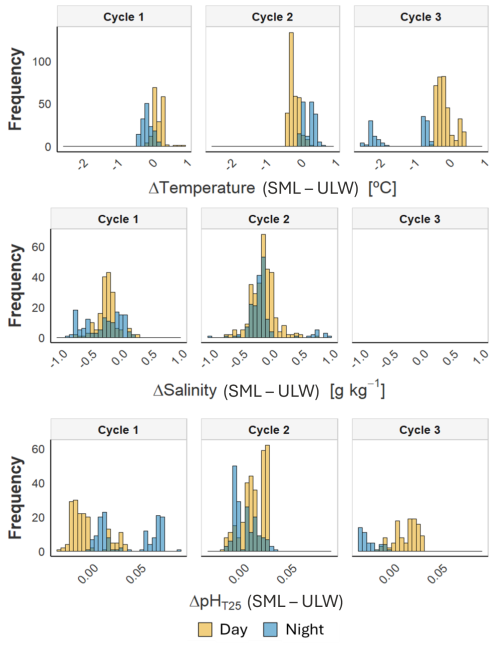

3.3 Diel variability and depth-related anomalies

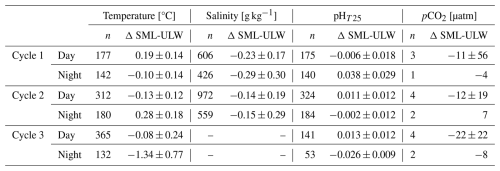

To assess diel variability in the marine carbon system, we statistically compared the thermohaline and key carbon cycle variables, pHT25 and pCO2, between day and night in the SML and ULW (Fig. 4, Table 2). Additionally, we calculated ΔSML-ULW to evaluate the magnitude of vertical anomalies during diurnal and nocturnal conditions. The analysis of thermohaline variables indicated significant differences between diurnal and nocturnal data at the two depths across the three cycles (Table S2). However, the salinity data recorded from ULW during Cycle 3 did not exhibit significant differences. The observed anomalies between the SML and ULW varied across the three cycles for temperature. In Cycle 1, the SML experienced positive diurnal and negative nocturnal temperature anomalies on average (0.19 ± 0.14; −0.10 ± 0.14 °C). During Cycle 2, negative diurnal SML anomalies and positive nocturnal anomalies were observed (−0.13 ± 0.12; 0.28 ± 0.18 °C). In Cycle 3, diurnal and nocturnal SML negative anomalies were detected at −0.08 ± 0.24 and −1.34 ± 0.77 °C, respectively. Likewise, it was noted that salinity anomalies in SML were negative in Cycles 1 and 2, both for diurnal (-0.23 ± 0.17; −0.14 ± 0.19 g kg−1) and nocturnal data (−0.29 ± 0.30; −0.15 ± 0.29 g kg−1). These results suggest that external factors may influence thermohaline variables, affecting the pronounced temporal distribution of the diel cycle.

Figure 4Frequency distribution of the anomaly of temperature, salinity, and pHT25 between SML and ULW observed during the day (orange) and at night (blue) across the three cycles studied.

When comparing the diurnal and nocturnal data for the variables associated with the marine carbon system at each depth, we found significant differences in pHT25, except for the ULW data during Cycle 3 (Table S2). However, no significant differences were observed in the pCO2 data. The pHT25 deltas (Table 2) revealed that during Cycle 1, lower pHT25 values were recorded in the SML for diurnal data and higher for nocturnal data (−0.006 ± 0.018; 0.038 ± 0.029). During Cycle 2, the SML showed higher diurnal (0.011 ± 0.012) and lower nocturnal (−0.002 ± 0.012) pHT25 values. Meanwhile, for Cycle 3, the SML indicated higher pHT25 values for the diurnal data (0.013 ± 0.012) and lower values for the nocturnal data (0.026 ± 0.009) (Table 2). For the pCO2 data during Cycles 1 and 3, lower pCO2 values were recorded in the SML during both diurnal (−11 ± 56 and −22 ± 22 µatm, respectively) and nocturnal periods (−4 and −8 µatm, respectively) (Table 2). In Cycle 2, lower diurnal and higher nocturnal values were observed in the SML, with values of −12 ± 19 and 7 µatm, respectively. The large variability between the nighttime and daytime data distributions at both depths reflects the influence of several environmental drivers acting on short timescales.

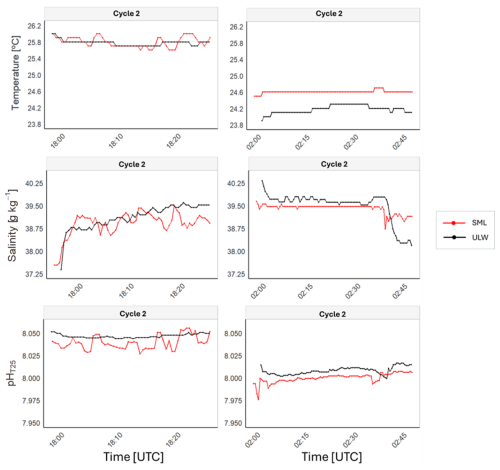

3.4 High-resolution variability of physicochemical parameters across diel cycles

To assess the variability of biogeochemical processes during the diel cycle, we present time series of temperature, salinity, and pHT25 (Fig. 5). In the time series, large fluctuations were primarily observed in the SML, particularly during the day. This increased variability is consistent with the patterns described in the previous section, although the standard deviations between SML and ULW are similar overall (Table S2). The changes during the day occurred rapidly, with increases and decreases spanning 3–5 min intervals for the three parameters. More specifically, during sampling at 18:00 UTC of Cycle 2, we recorded variations over brief intervals, specifically showing changes of approximately 0.28 °C in temperature, 0.30 g kg−1 in salinity, and 0.016 units in pHT25. During the night, fluctuations were less frequent and of smaller magnitude, except for a sudden change at the end of the sampling conducted at 02:00 UTC in Cycle 2. At that point, there was a slight increase in pHT25 at both SML and ULW, along with a decrease in salinity at both depths. This observation suggests that daytime surface heating, evaporation, and production processes likely result in changes in temperature, salinity, and pHT25, which are less pronounced at night.

Figure 5Time series data of temperature, salinity, and pHT25 collected during Cycle 2: Diurnal (18:00 UTC, 12 August) and Nocturnal (02:00 UTC, 13 August) measurements.

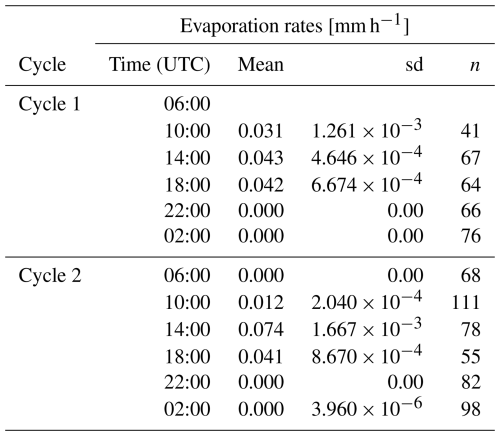

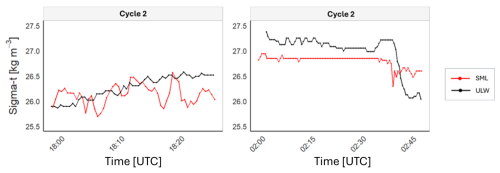

To assess the variability observed in the SML, the sigma-t time series for Cycle 2 at 18:00 and 02:00 UTC was plotted (Fig. 6), and evaporation rates within the SML were calculated for Cycles 1 and 2 (Table 3), as salinity data required for calculations in Cycle 3 were not available. The sigma-t time series throughout the day exhibits greater variability in the SML compared to nocturnal data, when density fluctuations decrease. However, this trend of variability was not observed in the ULW. The observed patterns of temperature, salinity, pHT25, and sigma-t align with the calculated evaporation rates. In Cycles 1 and 2, the evaporation rates peaked at 14:00 UTC (0.043 and 0.074 mm h−1, respectively). They remained high during the late afternoon at 18:00 UTC (0.042 and 0.041 mm h−1, respectively), coinciding with the periods of highest solar radiation and wind speed (Fig. 2). In contrast, the evaporation rate was close to zero at night. This behaviour highlights the influence of meteorological forcing on the SML during the day, underscoring the connection between evaporation and the observed variability.

Figure 6Time series during Cycle 2 for diurnal (18:00 UTC on 12 August) and nocturnal (02:00 UTC on 13 August) sigma-t data. Sigma-t is defined as the density at a given temperature and salinity minus 1000 kg m−3.

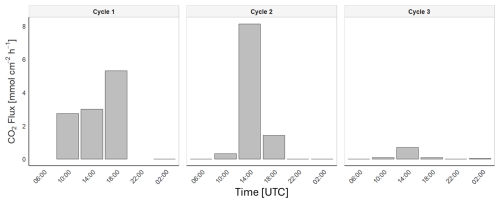

To study the gas exchange between the atmosphere and the ocean, we calculated the CO2 fluxes and k values using a wind-based parameterisation (Wanninkhof, 2014) for all three cycles and during both day and night (Fig. 7). In Cycle 1, despite the limited data, a flux of 3.64 ± 1.15 mmol cm−2 h−1 was detected during the day, while the flux was close to zero at night. A similar pattern appeared in Cycles 2 and 3, where the fluxes peaked at approximately 14:00 UTC and declined to near zero thereafter. However, the mean flux was higher in Cycle 2 (2.04 ± 3.18 mmol cm−2 h−1 ) than in Cycle 3 (0.21 ± 0.28 mmol cm−2 h−1), consistent with stronger winds. The average wind speeds during the day were 1.5, 1.9, and 0.4 m s−1 for each cycle, respectively, while at night, winds dropped to nearly 0 m s−1 in the three cycles. The k values during the day were 1.12 ± 0.15, 2.22 ± 3.31, and 0.09 ± 0.11 cm h−1, whereas at night, they were close to 0 cm h−1. In this context, excluding nocturnal fluxes in the daily average calculations introduced local percentage errors of 33 %, 50 %, and 43 % for Cycles 1, 2, and 3, respectively. The increased daytime wind speeds enhanced CO2 fluxes, whereas calm nighttime conditions were associated with reduced or nearly zero gas transfer velocities, consistent with the observed diel SML and ULW pCO2 variability (Fig. S2).

This study revealed high variability in the SML and ULW during the diel cycle, with significant differences (p<0.05) in temperature, salinity, and pHT25 when comparing diurnal and nocturnal data at both depths (Table S1). These results highlight the differences between the meteorological forces that influence the physicochemical properties of seawater during the day and night. During the day, the combined forcing of solar radiation and increased wind speed enhances evaporation rates (Table 3), leading to cooling the SML (Gassen et al., 2023), and driving short-term changes in temperature, salinity and pHT25 (Fig. 4). Although temperature strongly influences in situ carbonate chemistry (Zeebe and Wolf-Gladrow, 2001), pHT25 variations observed here do not result from a direct effect on carbonate speciation, but from temperature driven physical processes such as evaporation, which tends to increase salinity, alkalinity and thus pHT25, and vertical mixing, which can dilute this signal by introducing water with lower pHT25 and higher pCO2. These patterns reflect the stronger influence of surface forcing on the SML compared to the ULW. This means that the SML is subjected to short-term fluctuations that coincide with changes in wind speed. These fluctuations influence thermohaline features, CO2 system parameters (Acuña et al., 2008), and the kinetics of the metabolic processes occurring in the marine environment (Nimick et al., 2011). Accordingly, in response to the solar photocycle, many marine biogeochemical processes operate on a 24 h cycle (Nimick et al., 2011), with daily variations comparable in magnitude to the annual variations associated with the amount of solar radiation reaching the ocean surface at different times of the year (Herring et al., 1990; Nimick et al., 2011).

Regarding the variability observed during the day and night, we detected differences in the diurnal temperature data, reaching up to +1.89 °C in the SML and +1.36 °C in the ULW. Across the three cycles, the mean SML and ULW temperatures (Table S1) fall within the range expected for the Middle Adriatic Surface Water mass. Previous studies have reported mean summertime temperatures in the SML of 25.1 °C (Frka et al., 2009) and 27.4 ± 2.9 °C (Milinković et al., 2022). Interestingly, the negative diurnal SML anomalies in Cycles 2 and 3 differ from the typical low-wind patterns (Wurl et al., 2019), suggesting that localised mixing or evaporative cooling may have offset surface warming. In our study, strong stratification combined with weak winds likely promoted localised evaporative cooling and convection, offsetting the expected surface warming, as described in previous studies of near-surface instabilities (Cronin and Sprintall, 2001; Soloviev and Lukas, 2013). Similarly, the observed negative salinity anomaly in the SML could also be linked to these processes. While evaporation driven by intense solar radiation tends to increase salinity in the SML (Frka et al., 2009; Wurl et al., 2019), the consistently negative salinity anomalies observed in Cycles 1 and 2 (Table 2) suggest active vertical mixing, most likely associated with convective processes. This explains the daily variability in salinity distribution between the SML and ULW, with mean values of 39.09 ± 0.33 and 39.15 ± 0.34 g kg−1, respectively.

In this context, the contribution of external forcing factors, such as river discharge, precipitation, and tides, to the observed diurnal variability appears to be minimal. The Krka River has the highest outflow rates in the region, but it typically experiences lower discharge in the summer. This seasonal decrease in freshwater input contributes to the higher salinity values observed in both the SML and ULW compared to periods of stronger river discharge (Frka et al., 2009; Marcinek et al., 2020). Submarine groundwater discharge is also minor, between 0.19–0.31 m3 s−1 during dry periods (Liu et al., 2019), compared to its annual mean of 52.9 m3 s−1 (Bužančić et al., 2016; Marcinek et al., 2020). In addition, precipitation during the first half of August 2020 was very low, averaging 1.4 mm (Croatian Meteorological and Hydrological Service, 2020), further limiting freshwater input and variability in river flow. Similarly, tidal effects at this location are minimal, characterised by a microtidal range of 0.2 to 0.5 m (Cukrov et al., 2024a). Given the stable stratification of the estuary, such small tidal amplitudes are insufficient to generate significant tidally driven vertical mixing. Instead, the observed variability can be explained by localised near-surface mixing linked to evaporation, density instabilities, and short-term turbulence at the air–sea interface. Furthermore, the observed variability follows a diurnal (24 h) cycle rather than a semi-diurnal (12 h) cycle, reinforcing the interpretation that the patterns are primarily driven by surface warming and evaporation rather than tidal forcing (Wurl et al., 2019). This contrasts with mesotidal environments (e.g., Stolle et al., 2020), where tidal mixing complicates the detection of diurnal variability, highlighting the advantage of studying these processes in microtidal settings such as the Adriatic.

The interaction between biological processes and the physicochemical properties of seawater is complex (Álvarez et al., 2014; Cantoni et al., 2012) and has a delicate balance in the marine environment (Cantoni et al., 2012; Takahashi et al., 2002). This interaction directly influences biogeochemical processes typically regulated by production and respiration (Poulson and Sullivan, 2010). These processes significantly affect the pH of seawater through the uptake or removal of CO2. During the day, photosynthesis lowers pCO2 levels and increases pH by consuming CO2, whereas at night, CO2 from respiration accumulates, increasing pCO2 and decreasing pH (Ragazzola et al., 2021) . However, as we can see in Cycle 3 (Table S2), the observed increase in pCO2 (525 ± 47 µatm) and pHT25 (8.042 ± 0.020) values during the day compared to those measured at night (465 µatm; 7.993 ± 0.026) is largely consistent with the temperature dependence of CO2 solubility, as daytime warming naturally elevates pCO2 in surface waters (Takahashi et al., 1993; Weiss, 1974). This pattern likely reflects both the thermal effect and biological processes that can contribute to the diurnal increase in pCO2: enhanced respiration and CO2 accumulation in the upper layers of the water due to limited mixing may offset the anticipated photosynthetic uptake (Takahashi et al., 2002), while photoinhibition under solar radiation (Feng et al., 2008) could reduce photosynthesis efficiency. Taken together, these temperature-driven and metabolic processes provide a plausible explanation for the unexpected daytime increase in pCO2 despite favourable light conditions (Takahashi et al., 2002).

The complexity of the coupled thermohaline and pH dynamics in seawater is highlighted in the time-series results (Fig. 5). The observed fluctuations in the SML for temperature, salinity, and pHT25 may be due to buoyancy fluxes. Wind, thermohaline fluctuations, precipitation, and evaporation have a significant influence on surface turbulence (Cronin and Sprintall, 2001). The SML absorbs heat from sunlight and cools through radiation and heat loss, leading to changes in temperature and salinity that disrupt buoyancy, cause convective overturning, entrain deeper water from the ULW, and eventually promote mixing (Cronin and Sprintall, 2001). Wind can also enhance this process by creating tangential stress that acts as a vertical momentum flux. Temperature and salinity changes in the SML led to stratification or convection, with mixing, depending on oceanic and atmospheric forcing (Fig. 5). This process has already been observed in the SML (Wurl et al., 2019) and was found to regulate buoyancy fluxes through evaporative salinisation, playing a crucial role in the exchange of climate-relevant gases and heat between the ocean and the atmosphere.

In this context, the existence of these buoyancy fluxes only during the day could also explain the diel difference in CO2 exchange between the atmosphere and the ocean. As observed in this study, the CO2 fluxes exhibited differences between daytime (1.94 ± 2.45 mmol cm−2 h−1) and nighttime (0.01 ± 0.01 mmol cm−2 h−1) conditions. This pattern is consistent with the strong dependence of the gas transfer velocity (k) on wind forcing (Wanninkhof, 2014), confirming that wind is the dominant driver of diel variability. In addition, daytime buoyancy fluxes, enhanced by wind-driven evaporation and density instabilities, may further facilitate CO2 exchange during the day, amplifying the effect of wind. Additionally, the absence of wind at night reduced the calculated flux to nearly zero. This observation is consistent with previous suggestions that gas transfer velocity parameterisations without an intercept may underestimate conditions in very calm waters (Ribas-Ribas et al., 2019). Other processes, such as small-scale convection or vertical pCO2 gradients in the upper water column (Liss and Merlivat, 1986; Stolle et al., 2020), may also modulate short-term variability, but their contribution in our dataset appears minor compared to wind forcing. At the same time, SML properties themselves may contribute: slightly lower temperature and salinity enhance CO2 solubility, while reduced turbulence at the boundary layer further limits exchange.

Consistent with this, the SML pCO2 shows a considerable diel variability with a clear day–night shift in Cycle 1 (∼ 53 µatm), but smaller in Cycles 2 and 3 despite larger short-term amplitudes. Although these processes influence pCO2, their impact on CO2 fluxes remains small compared to the effect of k. This explains why flux differences are primarily driven by wind forcing. These patterns indicate that changes in solubility caused by temperature and the buoyancy-induced mixing determine most of the observed variability, rather than biologically driven changes. As a result, using only daytime pCO2 values leads to a slight overestimation of daily mean ΔpCO2 (e.g., +13 µatm in Cycle 1), but this effect is small compared to the much larger bias caused by neglecting nighttime fluxes. Temperature effects alone can account for a substantial fraction of diel pCO2 variability, given the well-established ∼ 4 % °C−1 sensitivity of seawater pCO2 to temperature (Takahashi et al., 2002; Zeebe and Wolf-Gladrow, 2001).The main implication of our results is that neglecting nocturnal fluxes leads to a systematic bias: the three diel cycles were overestimated by 33 %, 50 %, and 44 %, respectively. Thus, while wind remains the principal driver, accounting for variability in both k and pCO2 is essential to avoid biased daily estimates.

This study observed a clear diel variability in the distribution of thermohaline features and variables describing the marine inorganic carbon cycle, including temperature, salinity, pHT25, and pCO2. The SML experiences pronounced fluctuations in these parameters throughout the day, influenced by daily changes that alter near-surface stratification and mixing, mainly through evaporation-driven buoyancy fluxes and wind-induced turbulence. In addition, higher CO2 fluxes were observed during the day, coinciding with increased wind speeds and buoyancy fluxes that enhanced the exchange of CO2 between the two compartments. Although diel differences in pCO2 were detectable, our results suggest that this variability is largely consistent with temperature-dependent CO2 solubility and buoyancy-induced mixing, while a persistent biological day–night signal is not evident in this dataset. Thus, by emphasising the study of diel cycles, it has been observed that the daily variability of biogeochemical processes is in a delicate balance, making it challenging to obtain a comprehensive global understanding of marine chemistry.

To enhance understanding of these findings, implementing a comprehensive 24 h observational period is essential for accurately capturing the short-term variability that influences near-surface biogeochemistry. In recent decades, there have been technological advances in sampling equipment designed for short temporal and spatial scales. However, such progress has not been extended to nighttime observations, which remain significantly more challenging due to the greater logistical complexity and heightened safety considerations associated with operating aboard oceanographic vessels at night. In this context, it is essential to study complete diel cycles, which are crucial for understanding the global carbon budget and its associated uncertainties. Thus, generating a network of diurnal cycle data will identify the drivers of changes in marine chemistry, allowing for the assessment of the responses of marine ecosystems in the context of climate change.

The database supporting the findings of this study are available at PANGAEA. The complete set of collected data can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.984017 (Ribas-Ribas et al., 2025), which includes diel variability data, meteorological data, discrete bottle samples, and high-frequency measurements.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/os-21-3471-2025-supplement.

AL-P: Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing. OW: Funding Acquisition, Resources, Formal Analysis, Writing – Review & Editing. SF: Funding Acquisition, Resources, Formal Analysis, Writing – Review & Editing. MR-R: Conceptualisation, Formal Analysis, Visualization, Funding Acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

This article is part of the special issue “Biogeochemical processes and Air–sea exchange in the Sea-Surface microlayer (BG/OS inter-journal SI)”. It is not associated with a conference.

The author gratefully acknowledges the support from the Erasmus+ KA 131 SMP OUT program (2022–2023) for funding a research internship at the Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg – Institut für Chemie und Biologie des Meeres (ICBM). The authors thank Carola Lehners, Brandy T. Robinson, and Lisa Gassen for operating the sea surface scanner and conducting SML sampling, Carmen Cohr for initial S3 data treatment, and Leonie Jaeger for assistance with the evaporation rate calculations.

This research has been supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant no. 427614800), the Ministry of Science and Technology, Croatia (grant no. IP-2018-01-3105: Biochemical Responses of Oligotrophic Adriatic Surface Ecosystems to Atmospheric Deposition Inputs (BiREADI)), and the Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (Diurnal Dynamics at the Sea-Atmosphere Interface (INSIST) (grant no. 57513644)).

This paper was edited by Damian Leonardo Arévalo-Martínez and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Acuña, V., Wolf, A., Uehlinger, U., and Tockner, K.: Temperature dependence of stream benthic respiration in an alpine river network under global warming, Freshw. Biol., 53, 2076–2088, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2427.2008.02028.x, 2008.

Álvarez, M., Sanleón-Bartolomé, H., Tanhua, T., Mintrop, L., Luchetta, A., Cantoni, C., Schroeder, K., and Civitarese, G.: The CO2 system in the Mediterranean Sea: a basin wide perspective, Ocean Sci., 10, 69–92, https://doi.org/10.5194/os-10-69-2014, 2014.

Álvarez-Rodríguez, M.: The CO2 system observations in the Mediterranean Sea: past, present and future, in: Designing Med-SHIP: a program for repeated oceanographic surveys, CIESM Workshop Monographs, No. 43, edited by: Briand, F., CIESM, Monaco, 41–50, https://ciesm.org/catalog/index.php?article=1043 (last access: 14 January 2025), 2012.

Bergamasco, A. and Malanotte-Rizzoli, P.: The circulation of the Mediterranean Sea: a historical review of experimental investigations, Adv. Oceanogr. Limnol., 1, 11–28, https://doi.org/10.1080/19475721.2010.491656, 2010.

Borges, A. V.: Do we have enough pieces of the jigsaw to integrate CO2 fluxes in the coastal ocean?, Estuaries, 28, 3–27, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02732750, 2005.

Brutsaert, W.: Evaporation into the Atmosphere: Theory, History and Applications, Environmental Fluid Mechanics, Springer, Dordrecht, Netherlands, 302 pp., https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-1497-6, 2013.

Bužančić, M., Gladan, Ž. N., Marasović, I., Kušpilić, G., and Grbec, B.: Eutrophication influence on phytoplankton community composition in three bays on the eastern Adriatic coast, Oceanologia, 58, 302–316, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceano.2016.05.003, 2016.

Cantoni, C., Luchetta, A., Celio, M., Cozzi, S., Raicich, F., and Catalano, G.: Carbonate system variability in the Gulf of Trieste (North Adriatic Sea), Estuarine, Coastal Shelf Sci., 115, 51–62, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2012.07.006, 2012.

Cantoni, C., Luchetta, A., Chiggiato, J., Cozzi, S., Schroeder, K., and Langone, L.: Dense water flow and carbonate system in the southern Adriatic: A focus on the 2012 event, Mar. Geol., 375, 15–27, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2015.08.013, 2016.

Cetinić, I., Viličić, D., Burić, Z., and Olujić, G.: Phytoplankton seasonality in a highly stratified karstic estuary (Krka, Adriatic Sea), Hydrobiologia, 555, 31–40, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-005-1107-6, 2006.

Croatian Meteorological and Hydrological Service: Precipitation data for August 2020, https://meteo.hr (last access: 19 September 2025), 2020.

Cronin, M. F. and Sprintall, J.: Wind-and buoyancy-forced upper ocean, in: Elements of Physical Oceanography: A Derivative of the Encyclopedia of Ocean Sciences, 237–245, https://doi.org/10.1006/rwos.2001.0157, 2001.

Cukrov, N., Cindrić, A.-M., Omanović, D., and Cukrov, N.: Spatial distribution, ecological risk assessment, and source identification of metals in sediments of the Krka River Estuary (Croatia), Sustainability, 16, 1800, https://doi.org/10.3390/su16051800, 2024a.

Cukrov, N., Cukrov, N., and Omanović, D.: Early diagenetic processes in the sediments of the Krka River Estuary, J. Mar. Sci. Eng., 12, 466, https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse12030466, 2024b.

Cunliffe, M., Engel, A., Frka, S., Gašparović, B., Guitart, C., Murrell, J. C., Salter, M., Stolle, C., Upstill-Goddard, R., and Wurl, O.: Sea surface microlayers: A unified physicochemical and biological perspective of the air–ocean interface, Prog. Oceanogr., 109, 104–116, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pocean.2012.08.004, 2013.

De Montety, V., Martin, J. B., Cohen, M. J., Foster, C., and Kurz, M. J.: Influence of diel biogeochemical cycles on carbonate equilibrium in a karst river, Chem. Geol., 283, 31–43, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2010.12.025, 2011.

del Giorgio, P. and Williams, P. (Eds.): Respiration in Aquatic Ecosystems, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 320 pp., ISBN 9780198527084, 2005.

Dickson, A. G. and Millero, F. J.: A comparison of the equilibrium constants for the dissociation of carbonic acid in seawater media, Deep Sea Res. Part A, 34, 1733–1743, https://doi.org/10.1016/0198-0149(87)90021-5, 1987.

Dickson, A. G., Sabine, C. L., and Christian, J. R.: Guide to best practices for ocean CO2 measurements, PICES Special Publication 3, North Pacific Marine Science Organization, 191 pp., ISBN 1-897176-07-4, 2007.

Doney, S. C., Fabry, V. J., Feely, R. A., and Kleypas, J. A.: Ocean Acidification: The Other CO2 Problem, Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci., 1, 169–192, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.marine.010908.163834, 2009.

Engel, A., Bange, H. W., Cunliffe, M., Burrows, S. M., Friedrichs, G., Galgani, L., Herrmann, H., Hertkorn, N., Johnson, M., Liss, P. S., Quinn, P. K., Schartau, M., Soloviev, A., Stolle, C., Upstill-Goddard, R. C., Van Pinxteren, M., and Zäncker, B.: The ocean's vital skin: toward an integrated understanding of the sea surface microlayer, Front. Mar. Sci., 4, 165, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2017.00165, 2017.

Fanning, K. A. and Pilson, M.: On the Spectrophotometric determination of dissolved silica in natural waters, Anal. Chem., 45, 136–140, https://doi.org/10.1021/ac60323a021, 1973.

Feng, Y., Warner, M. E., Zhang, Y., Sun, J., Fu, F.-X., Rose, J. M., and Hutchins, D. A.: Interactive effects of increased pCO2, temperature and irradiance on the marine coccolithophore Emiliania huxleyi (Prymnesiophyceae), Eur. J. Phycol., 43, 87–98, https://doi.org/10.1080/09670260701664674, 2008.

Friedlingstein, P., O'Sullivan, M., Jones, M. W., Andrew, R. M., Hauck, J., Landschützer, P., Le Quéré, C., Li, H., Luijkx, I. T., Olsen, A., Peters, G. P., Peters, W., Pongratz, J., Schwingshackl, C., Sitch, S., Canadell, J. G., Ciais, P., Jackson, R. B., Alin, S. R., Arneth, A., Arora, V., Bates, N. R., Becker, M., Bellouin, N., Berghoff, C. F., Bittig, H. C., Bopp, L., Cadule, P., Campbell, K., Chamberlain, M. A., Chandra, N., Chevallier, F., Chini, L. P., Colligan, T., Decayeux, J., Djeutchouang, L. M., Dou, X., Duran Rojas, C., Enyo, K., Evans, W., Fay, A. R., Feely, R. A., Ford, D. J., Foster, A., Gasser, T., Gehlen, M., Gkritzalis, T., Grassi, G., Gregor, L., Gruber, N., Gürses, Ö., Harris, I., Hefner, M., Heinke, J., Hurtt, G. C., Iida, Y., Ilyina, T., Jacobson, A. R., Jain, A. K., Jarníková, T., Jersild, A., Jiang, F., Jin, Z., Kato, E., Keeling, R. F., Klein Goldewijk, K., Knauer, J., Korsbakken, J. I., Lan, X., Lauvset, S. K., Lefèvre, N., Liu, Z., Liu, J., Ma, L., Maksyutov, S., Marland, G., Mayot, N., McGuire, P. C., Metzl, N., Monacci, N. M., Morgan, E. J., Nakaoka, S.-I., Neill, C., Niwa, Y., Nützel, T., Olivier, L., Ono, T., Palmer, P. I., Pierrot, D., Qin, Z., Resplandy, L., Roobaert, A., Rosan, T. M., Rödenbeck, C., Schwinger, J., Smallman, T. L., Smith, S. M., Sospedra-Alfonso, R., Steinhoff, T., Sun, Q., Sutton, A. J., Séférian, R., Takao, S., Tatebe, H., Tian, H., Tilbrook, B., Torres, O., Tourigny, E., Tsujino, H., Tubiello, F., van der Werf, G., Wanninkhof, R., Wang, X., Yang, D., Yang, X., Yu, Z., Yuan, W., Yue, X., Zaehle, S., Zeng, N., and Zeng, J.: Global Carbon Budget 2024, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 17, 965–1039, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-17-965-2025, 2025.

Frka, S., Kozarac, Z., and Ćosović, B.: Characterization and seasonal variations of surface active substances in the natural sea surface micro-layers of the coastal Middle Adriatic stations, Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci., 85, 555–564, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2009.09.023, 2009.

Garbe, C. S., Rutgersson, A., Boutin, J., De Leeuw, G., Delille, B., Fairall, C. W., Gruber, N., Hare, J., Ho, D. T., Johnson, M. T., Nightingale, P. D., Pettersson, H., Piskozub, J., Sahlée, E., Tsai, W., Ward, B., Woolf, D. K., and Zappa, C. J.: Transfer across the air–sea interface, in: Ocean–Atmosphere Interactions of Gases and Particles, edited by: Liss, P. S. and Johnson, M. T., Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany, 55–112, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-25643-1_2, 2014.

Gassen, L., Badewien, T. H., Ewald, J., Ribas-Ribas, M., and Wurl, O.: Temperature and Salinity Anomalies in the Sea Surface Microlayer of the South Pacific during Precipitation Events, J. Geophys. Res. Oceans, e2023JC019638, https://doi.org/10.1029/2023JC019638, 2023.

Gattuso, J.-P., Allemand, D., and Frankignoulle, M.: Photosynthesis and calcification at cellular, organismal and community levels in coral reefs: a review on interactions and control by carbonate chemistry, Am. Zool., 39, 160–183, https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/39.1.160, 1999.

Gattuso, J.-P., Magnan, A., Billé, R., Cheung, W. W. L., Howes, E. L., Joos, F., Allemand, D., Bopp, L., Cooley, S. R., Eakin, C. M., Hoegh-Guldberg, O., Kelly, R. P., Pörtner, H.-O., Rogers, A. D., Baxter, J. M., Laffoley, D., Osborn, D., Rankovic, A., Rochette, J., Sumaila, U. R., Treyer, S., and Turley, C.: Contrasting futures for ocean and society from different anthropogenic CO2 emissions scenarios, Science, 349, aac4722, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aac4722, 2015.

Hassoun, A. E. R., Gemayel, E., Krasakopoulou, E., Goyet, C., Abboud-Abi Saab, M., Guglielmi, V., Touratier, F., and Falco, C.: Acidification of the Mediterranean Sea from anthropogenic carbon penetration, Deep Sea Res. Part I, 102, 1–15, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr.2015.04.005, 2015.

Hassoun, A. E. R., Bantelman, A., Canu, D., Comeau, S., Galdies, C., Gattuso, J.-P., Giani, M., Grelaud, M., Hendriks, I. E., Ibello, V., Idrissi, M., Krasakopoulou, E., Shaltout, N., Solidoro, C., Swarzenski, P. W., and Ziveri, P.: Ocean acidification research in the Mediterranean Sea: Status, trends and next steps, Front. Mar. Sci., 9, 892670, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2022.892670, 2022.

Herring, P. J., Campbell, A. K., Whitfeld, M., and Maddock, L. (Eds.): Light and Life in the Sea, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 366 pp., ISBN 978-0521392075, 1990.

Hoegh-Guldberg, O., Cai, R., Poloczanska, E. S., Brewer, P. G., Sundby, S., Hilmi, K., Fabry, V. J., Jung, S., Skirving, W., and Stone, D. A.: The ocean, in: Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part B: Regional Aspects, edited by: Barros, V. R., Field, C. B., Dokken, D. J., Mastrandrea, M. D., Mach, K. J., Bilir, T. E., Chatterjee, M., Ebi, K. L., Estrada, Y. O., Genova, R. C., Girma, B., Kissel, E. S., Levy, A. N., MacCracken, S., Mastrandrea, P. R., and White, L. L., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 1655–1731, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415386.010, 2014.

Humphreys, M. P., Lewis, E. R., Sharp, J. D., and Pierrot, D.: PyCO2SYS v1.8: marine carbonate system calculations in Python, Geosci. Model Dev., 15, 15–43, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-15-15-2022, 2022.

IPCC: Climate Change 2021 – The Physical Science Basis, Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896, 2023.

Kapsenberg, L., Alliouane, S., Gazeau, F., Mousseau, L., and Gattuso, J.-P.: Coastal ocean acidification and increasing total alkalinity in the northwestern Mediterranean Sea, Ocean Sci., 13, 411–426, https://doi.org/10.5194/os-13-411-2017, 2017.

Kittel, C. and Kroemer, H.: Thermal Physics, Macmillan, ISBN 978-0716710882, 1980.

Laskov, C., Herzog, C., Lewandowski, J., and Hupfer, M.: Miniaturized photometrical methods for the rapid analysis of phosphate, ammonium, ferrous iron, and sulfate in pore water of freshwater sediments, Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods, 5, 63–71, https://doi.org/10.4319/lom.2007.5.63, 2007.

Lee, K., Kim, T.-W., Byrne, R. H., Millero, F. J., Feely, R. A., and Liu, Y.-M.: The universal ratio of boron to chlorinity for the North Pacific and North Atlantic oceans, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 74, 1801–1811, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2009.12.027, 2010.

Liss, P. S. and Merlivat, L.: Air–sea gas exchange rates: introduction and synthesis, in: The Role of Air–Sea Exchange in Geochemical Cycling, edited by: Buat-Ménard, P., Springer, Dordrecht, Netherlands, 113–127, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-4738-2_5, 1986.

Liu, J., Hrustić, E., Du, J., Gašparović, B., Čanković, M., Cukrov, N., Zhu, Z., and Zhang, R.: Net submarine groundwater-derived dissolved inorganic nutrients and carbon input to the oligotrophic stratified karstic estuary of the Krka River (Adriatic Sea, Croatia), J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans, 124, 4334–4349, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JC014814, 2019.

Marcinek, S., Santinelli, C., Cindrić, A.-M., Evangelista, V., Gonnelli, M., Layglon, N., Mounier, S., Lenoble, V., and Omanović, D.: Dissolved organic matter dynamics in the pristine Krka River estuary (Croatia), Mar. Chem., 225, 103848, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marchem.2020.103848, 2020.

Mehrbach, C., Culberson, C. H., Hawley, J. E., and Pytkowicx, R. M.: Measurement of the apparent dissociation constants of carbonic acid in seawater at atmospheric pressure 1, Limnol. Oceanogr., 18, 897–907, https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.1973.18.6.0897, 1973.

Milinković, A., Penezić, A., Kušan, A. C., Gluščić, V., Žužul, S., Skejić, S., Šantić, D., Godec, R., Pehnec, G., Omanović, D., Engel, A., and Frka, S.: Variabilities of biochemical properties of the sea surface microlayer: Insights to the atmospheric deposition impacts, Sci. Total Environ., 838, 156440, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.156440, 2022.

Nimick, D. A., Gammons, C. H., and Parker, S. R.: Diel biogeochemical processes and their effect on the aqueous chemistry of streams: A review, Chem. Geol., 283, 3–17, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2010.08.017, 2011.

Orr, J. C., Fabry, V. J., Aumont, O., Bopp, L., Doney, S. C., Feely, R. A., Gnanadesikan, A., Gruber, N., Ishida, A., Joos, F., Key, R. M., Lindsay, K., Maier-Reimer, E., Matear, R., Monfray, P., Mouchet, A., Najjar, R. G., Plattner, G.-K., Rodgers, K. B., Sabine, C. L., Sarmiento, J. L., Schlitzer, R., Slater, R. D., Totterdell, I. J., Weirig, M.-F., Yamanaka, Y., and Yool, A.: Anthropogenic ocean acidification over the twenty-first century and its impact on calcifying organisms, Nature, 437, 681–686, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04095, 2005.

Pecci, M., di Sarra, A., Sferlazzo, D., Anello, F., Di Iorio, T., Colella, S., Iaccarino, A., Marullo, S., Meloni, D., Monteleone, F., Pace, G., and Piacentino, S.: Ocean–atmosphere CO2 flux at the Lampedusa Oceanographic Observatory, https://www.lampedusa.enea.it/dataaccess/ocean_co2fluxes (last access: 19 August 2025), 2023.

Perez, F. F. and Fraga, F.: Association constant of fluoride and hydrogen ions in seawater, Mar. Chem., 21, 161–168, https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4203(87)90036-3, 1987.

Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D. C., Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E., and Weyer, N. M.: The ocean and cryosphere in a changing climate, IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate, 1155 pp., https://www.ipcc.ch/srocc/ (last access: 19 January 2025), 2019.

Poulson, S. R. and Sullivan, A. B.: Assessment of diel chemical and isotopic techniques to investigate biogeochemical cycles in the upper Klamath River, Oregon, USA, Chem. Geol., 269, 3–11, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2009.05.016, 2010.

Prohić, E. and Juračić, M.: Heavy metals in sediments – problems concerning determination of the anthropogenic influence: study in the Krka River estuary, eastern Adriatic coast, Yugoslavia, Environ. Geol. Water Sci., 13, 145–151, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01664699, 1989.

Ragazzola, F., Kolzenburg, R., Adani, M., Bordone, A., Cantoni, C., Cerrati, G., Ciuffardi, T., Cocito, S., Luchetta, A., Montagna, P., Nannini, M., Page, D. C., Peirano, A., Raiteri, G., and Lombardi, C.: Carbonate chemistry and temperature dynamics in an alga dominated habitat, Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci., 44, 101770, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rsma.2021.101770, 2021.

Ribas-Ribas, M., Battaglia, G., Humphreys, M. P., and Wurl, O.: Impact of nonzero intercept gas transfer velocity parameterizations on global and regional ocean–atmosphere CO2 fluxes, Geosciences, 9, 230, https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences9050230, 2019.

Ribas-Ribas, M., Hamizah Mustaffa, N. I., Rahlff, J., Stolle, C., and Wurl, O.: Sea Surface Scanner (S3): A catamaran for high-resolution measurements of biogeochemical properties of the sea surface microlayer, J. Atmos. Oceanic Technol., 34, 1433–1448, https://doi.org/10.1175/JTECH-D-17-0017.1, 2017.

Ribas-Ribas, M., López-Puertas, A., Wurl, O., and Frka, S.: Diel variability of thermohaline and carbon system parameters in the sea-surface microlayer and underlying water of a Mediterranean coastal site (Šibenik, Croatia), PANGAEA, [data set], https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.984017, 2025.

Robinson, A. R. and Golnaraghi, M.: The Physical and Dynamical Oceanography of the Mediterranean Sea, in: Ocean Processes in Climate Dynamics: Global and Mediterranean Examples, edited by: Malanotte-Rizzoli, P. and Robinson, A. R., Springer Netherlands, 255–306, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-0870-6_12, 1994.

RStudio Team: RStudio: integrated development environment for R, Posit Software, Boston, MA, USA, posit [code], https://posit.co/ (last access: 25 March 2025), 2023.

Schlitzer, R.: Ocean Data View, Alfred-Wegener-Institut [software], https://epic.awi.de/id/eprint/56921/ (last access: 10 December 2025), 2022.

Schneider, A., Tanhua, T., Körtzinger, A., and Wallace, D. W. R.: High anthropogenic carbon content in the eastern Mediterranean, J. Geophys. Res. Oceans, 115, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010JC006171, 2010.

Sharp, J. D., Pierrot, D., Humphreys, M. P., Epitalon, J.-M., Orr, J. C., Lewis, E. R., and Wallace, D. W. R.: CO2SYSv3 for MATLAB (v3.1), Zenodo [code], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4023039, 2020

Shaw, E. C., McNeil, B. I., and Tilbrook, B.: Impacts of ocean acidification in naturally variable coral reef flat ecosystems, J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans, 117, C03038, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011JC007655, 2012.

Soloviev, A. and Lukas, R.: The Near-Surface Layer of the Ocean: Structure, Dynamics and Applications, 2nd edn., Springer, Dordrecht, the Netherlands, 572 pp., ISBN 94-007-7621-7, 2013.

Stolle, C., Ribas-Ribas, M., Badewien, T. H., Barnes, J., Carpenter, L. J., Chance, R., Damgaard, L. R., Durán Quesada, A. M., Engel, A., Frka, S., Galgani, L., Gašparović, B., Gerriets, M., Hamizah Mustaffa, N. I., Herrmann, H., Kallajoki, L., Pereira, R., Radach, F., Revsbech, N. P., and Wurl, O.: The MILAN campaign: studying diel light effects on the air–sea interface, B. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 101, E146–E166, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-17-0329.1, 2020.

Takahashi, T., Olafsson, J., Goddard, J. G., Chipman, D. W., and Sutherland, S. C.: Seasonal variation of CO2 and nutrients in the high-latitude surface oceans: A comparative study, Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles, 7, 843–878, https://doi.org/10.1029/93GB02263, 1993.

Takahashi, T., Sutherland, S. C., Sweeney, C., Poisson, A., Metzl, N., Tilbrook, B., Bates, N., Wanninkhof, R., Feely, R. A., Sabine, C., Olafsson, J., and Nojiri, Y.: Global sea–air CO2 flux based on climatological surface ocean pCO2, and seasonal biological and temperature effects, Deep-Sea Res. Pt. II, 49, 1601–1622, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0967-0645(02)00003-6, 2002.

Takahashi, T., Sutherland, S. C., Chipman, D. W., Goddard, J. G., Ho, C., Newberger, T., Sweeney, C., and Munro, D. R.: Climatological distributions of pH, pCO2, total CO2, alkalinity, and CaCO3 saturation in the global surface ocean, and temporal changes at selected locations, Mar. Chem., 164, 95–125, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marchem.2014.06.004, 2014.

Van Heuven, S., Pierrot, D., Rae, J. W. B., Lewis, E., and Wallace, D. W. R.: MATLAB Program Developed for CO2 System Calculations, Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center (CDIAC), Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) [code], https://github.com/jamesorr/CO2SYS-MATLAB (last access: 10 December 2025), 2011.

Wanninkhof, R.: Relationship between wind speed and gas exchange over the ocean revisited, Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods, 12, 351–362, https://doi.org/10.4319/lom.2014.12.351, 2014.

Weiss, R. F.: Carbon dioxide in water and seawater: The solubility of a non-ideal gas, Mar. Chem., 2, 203–215, https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4203(74)90015-2, 1974.

Wong, P. P., Losada, I. J., Gattuso, J.-P., Hinkel, J., Khattabi, A., McInnes, K. L., Saito, Y., and Sallenger, A.: Coastal systems and low-lying areas, in: Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects, Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by: Field, C. B., Barros, V. R., Dokken, D. J., Mach, K. J., Mastrandrea, M. D., Bilir, T. E., Chatterjee, M., Ebi, K. L., Estrada, Y. O., Genova, R. C., Girma, B., Kissel, E. S., Levy, A. N., MacCracken, S., Mastrandrea, P. R., and White, L. L., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 361–409, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415379.010, 2014.

Wurl, O., Wurl, E., Miller, L., Johnson, K., and Vagle, S.: Formation and global distribution of sea-surface microlayers, Biogeosciences, 8, 121–135, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-8-121-2011, 2011.

Wurl, O., Ekau, W., Landing, W. M., and Zappa, C. J.: Sea surface microlayer in a changing ocean – a perspective, Elem. Sci. Anthropocene, 5, 31, https://doi.org/10.1525/elementa.228, 2017.

Wurl, O., Landing, W. M., Mustaffa, N. I. H., Ribas-Ribas, M., Witte, C. R., and Zappa, C. J.: The Ocean's Skin Layer in the Tropics, in: Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 124, 59–74, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JC014021, 2019.

Yates, K. K., Dufore, C., Smiley, N., Jackson, C., and Halley, R. B.: Diurnal variation of oxygen and carbonate system parameters in Tampa Bay and Florida Bay, Mar. Chem., 104, 110–124, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marchem.2006.12.008, 2007.

Zeebe, R. E. and Wolf-Gladrow, D. A.: CO2 in Seawater: Equilibrium, Kinetics, Isotopes, Elsevier Oceanography Series, vol. 65, Elsevier, Amsterdam, ISBN 0444509461, 2001.

Zutic, V. and Legovic, T.: A film of organic matter at the fresh-water/sea-water interface of an estuary, Nature, 328, 612–614, https://doi.org/10.1038/328612a0, 1987.