the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Modelling river-sea continuum: the case of the Danube Delta

Christian Ferrarin

Debora Bellafiore

Alejandro Paladio Hernandez

Irina Dinu

Adrian Stanica

Understanding water transport and circulation in coastal seas and transitional environments is a key focus of oceanographic and climate research, particularly in recognizing the role of the land-sea interface. The Danube Delta serves as a natural laboratory for river-sea hydrodynamic modelling due to its complex morphology, composed of multiple river branches, channels, and lagoons. Moreover, this coastal environment is subjected to various natural and anthropogenic stressors, and numerical modelling can provide a scientific basis for assessing the impact of human activities. In this work, the SHYFEM finite element hydrodynamic model was applied to the entire river-sea continuum of the Danube Delta region to describe the transport and mixing processes within and between the interconnected water bodies forming the delta. The model was run for the period 2015-2019 and enabled the characterization of: (1) water discharge distribution among the river branches; (2) general hydrodynamic characteristics of the coastal region of freshwater influence; (3) transport time scale of the Razelm Sinoie Lagoon System. Finally, the Danube Delta modelling tool was used to evaluate the potential effects of hydrological reconnection (restoration) measures in the Razelm Sinoie Lagoon System aimed at improving connectivity and water renewal.

- Article

(15627 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Coastal environments at the river-sea interface, like estuaries and deltas, are critical components of coastal ecosystems due to their importance in supporting biodiversity and providing ecosystem services such as nutrient cycling, carbon sequestration, and habitat for marine life (Newton et al., 2023, and references therein). However, these regions are highly sensitive to both natural events (e.g., storms, sea-level rise, droughts) and anthropogenic pressures (e.g., damming, land reclamation, pollution). As such, modelling these environments is essential for understanding their dynamics, predicting their responses to environmental change, and guiding sustainable management practices.

Modelling estuaries and deltas is challenging due to their complex morphology made of different components such as river network, coastal lakes, lagoons, creeks, marshes. These different water compartments are generally interconnected and thus influencing each other. Accurately capturing the exchange of water and energy in complex coastal systems requires a comprehensive description of both the general coastal circulation and the fine-scale hydrodynamic processes occurring at river mouth and inlets. Particular attention must be paid to describing narrow channels, secondary river branches, and areas subject to periodic wetting and drying, such as tidal marshes and river floodplains.

To meet this constraint and limit computation time, unstructured or flexible mesh models with variable element resolution are preferable to structured mesh models (rectangular grids). Unstructured ocean models, like SCHISM (Zhang et al., 2016), SHYFEM (Umgiesser et al., 2022), FESOM-C (Androsov et al., 2019), Delft3D (Deltares, 2023), TELEMAC (Telemac-Mascaret, 2022), ADCIRC (Zhang and Yu, 2025), FVCOM (Chen et al., 2003), SLIM (Vallaeys et al., 2018) have proven to be powerful tools for simulating complex hydrodynamics in estuarine and deltaic environments. These models help assess the effects of climate change (Ferrarin et al., 2014; Pein et al., 2023), human interventions (Ferrarin et al., 2013; Thanh et al., 2020), and natural variability on the structure and functioning of coastal systems (Maicu et al., 2018; Zhu et al., 2020; Feizabadi et al., 2024).

The numerical representation of the land-sea continuum requires a numerical domain that extends upstream into the river network and offshore into the open sea. While a vertically integrated barotropic model is generally sufficient for reproducing the circulation along the river course and in shallow coastal environments, a 3D approach must be adopted in coastal environments influenced by freshwater (Horner-Devine et al., 2015). Such an approach has been widely adopted to model processes in several deltas and estuaries. Some model applications are saltwater intrusion in the Pearl River Delta (China) (Shen et al., 2018; Payo-Payo et al., 2022), hydrodynamics and saltwater intrusion in the Po Delta and adjacent coastal area (Italy) (Maicu et al., 2018; Bellafiore et al., 2021), river plume dynamics in the Columbia River (USA) (Vallaeys et al., 2018), flooding in the Mekong Delta (Vietnam) (Thanh et al., 2020), hydrological connectivity in the Wax Lake Delta (USA) (Feizabadi et al., 2024), tidal intrusion in the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna mega delta (Bangladesh) (Bricheno et al., 2016), among others. Models used in estuarine and delta research often integrate hydrodynamics, sediment transport, water quality, and ecological processes. However, the greater the complexity of the processes to be investigated, the higher is the amount of data needed for the model implementation and testing.

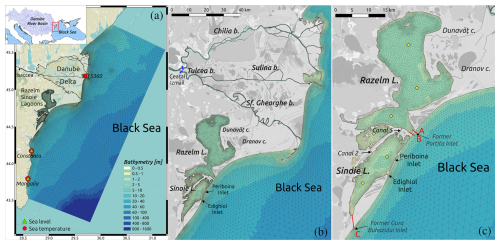

This research aims to numerically investigate the hydrodynamic processes driving the water exchange and connectivity among the various interconnected water compartments – river branches, channels, lagoons, and the coastal sea – that together form the Danube Delta river-sea continuum. The SHYFEM model (System of HydrodYnamic Finite Element Modules; Umgiesser et al., 2022) is used to quantify the distribution of water discharge among river branches, assess the influence of multiple river plumes on coastal dynamics, and analyze the water exchange and renewal capacity of the Razelm Sinoie Lagoon System. Moreover, the numerical tool is used to assess the potential impacts of different hypothetical lagoon-sea reconnection solutions (what-if scenarios) on the processes regulating the exchanges between the river, lagoon, and sea. To achieve this, we implemented the SHYFEM model across the entire Danube Delta, encompassing approximately 500 km of the river network, the Razelm Sinoie Lagoon System, and part of the prodelta coastal sea (Fig. 1).

1.1 The Danube Delta

The Danube Delta is the final part of the Danube River's journey of almost 2900 km, crossing 10 countries and draining a hydrographic basin of over 800 000 km2 from 19 states towards its connection with the Black Sea (e.g., Panin, 1998). The Danube Delta plain begins at the first bifurcation of the Danube, called Ceatal Izmail (Fig. 1). Here, the Danube River divides into two distributaries: the northern one, Chilia, and the southern one, Tulcea. The Chilia distributary creates a natural border between Romania and Ukraine. The Tulcea distributary divides again at Ceatal, 17 km farther downstream, into two other branches, Sulina and Sf. Gheorghe. The fluvial delta plain covers 4000 km2 and the marine one covers 1800 km2. Floodplains play a critical role in the Danube Delta by providing flood control, water purification, groundwater replenishment, and habitat for diverse species like fish and birds (Frank et al., 2025).

The Romanian section of the Danube Delta, including the Razelm-Sinoie Lagoon System (hereinafter RSLS), was designated a Biosphere Reserve in 1991 under UNESCO's “Man and the Biosphere” Programme and has remained a Nature Reserve ever since. RSLS extends for about 1000 km2 and is located in the southern part of the Danube Delta Biosphere Reserve. RSLS is a semiclosed shallow water body (the average depth is 1.8 m) receiving Danube freshwater from the Dunavǎţ and Dranov canals and exchanging waters with the Black Sea via the Edighiol and Periboina inlets. The lagoon system is suffering from poor water renewal and stagnation (Dinu et al., 2015) and has been significantly affected by human interventions since the end of the 19th century (Panin, 1996, 1998, 1999; Giosan et al., 2006; Vespremeanu-Stroe et al., 2013; Constantinescu et al., 2023). Dredging works to connect the Razelm lagoon to the Sf. Gheorghe arm of the Danube via the Dunavǎţ and Dranov canals were finalized at the beginning of the 20th century. As a result, more fresh water is discharged into the lagoon system. During the 1950s, management plans were made to decrease the salinity in the lagoon system, with the purpose to increase the freshwater fish culture productivity. Between 1960 and 1990, the lagoon has been used mainly for irrigations and, secondly, for fish breeding. In 1973, the Portiţa Inlet of the Razelm Lagoon was completely closed by a system of breakwaters and groins. Following the closure of the Portiţa inlet, the Razelm Lagoon was transformed into a freshwater lake, receiving Danube water via Dranov and Dunavǎţ Canals. The inlet of Gura Buhazului in the southern part of the Sinoie Lagoon was clogged more than 3 decades ago (late 1980s–early 1990s). The permanent circulation between the Sinoie Lagoon and the Black Sea has been restored by the beginning of the 2000s, being controlled by the Periboina and Edighiol inlets. The Periboina inlet has become clogged around 2017, with an intermittent connection with the sea during spring and autumn months up to the year 2021. As part of the master plan for the protection of the Romanian Littoral against erosion, a major hydraulic engineering project is currently implemented, to ensure a permanent water exchange through the Periboina Inlet.

The Danube River before the delta has an average water discharge of 6500 m3 s−1, with values ranging from 1300 to 16 000 m3 s−1 (Pekárová et al., 2021). The two major wind regimes characterizing the study area are from north-east, being the most intense, and south-south-west, that can drive alongshore water and sediment transport (Dan et al., 2009).

2.1 The modelling system

In this study, we used the SHYFEM model (System of HydrodYnamic Finite Element Modules, Umgiesser et al., 2022) to simulate the three-dimensional (3D) hydrodynamics of the river-sea continuum across the entire Danube Delta region. SHYFEM is an open-source, unstructured ocean model designed to simulate hydrodynamics and transport processes at very high resolution. It solves the primitive equations using an unstructured finite element method in the horizontal and a z coordinate system in the vertical. Vertical viscosity and diffusivity are calculated by the k−e turbulence closure module of the General Ocean Turbulence Model (Burchard and Petersen, 1999). The model has previously been applied to simulate hydrodynamics in the Mediterranean Sea (Ferrarin et al., 2018), the Adriatic Sea (Bellafiore et al., 2018; Ferrarin et al., 2019), the Black Sea (Bajo et al., 2014), and several coastal systems (Ferrarin et al., 2021; Umgiesser et al., 2022).

SHYFEM was applied to model the river network of the Danube Delta from Isaccea (100 km upstream from the river mouths, in the vicinity of the delta apex at Ceatal Izmail) to the sea (from north to south the Chilia, Sulina and Sf. Gheorghe branches), the Razelm Sinoie Lagoon System, the nearby prodelta and shelf area (290×100 km) and the narrow canals and inlets connecting the different water compartments (Dunavǎţ, Dranov, Canal 2, Canal 5, Edighiol and Periboina) (Fig. 1). The numerical grid does not include the delta floodplain system – comprising channels, wetlands, lakes, and marshes – as simulating flood dynamics over these areas is beyond the scope of this study.

The application of a triangular unstructured grid in the hydrodynamic model has the advantage of describing accurately complicated bathymetry and irregular boundaries in the river and shallow water areas. It can also solve the combined offshore-coastal interactions and small-scale river-sea dynamics in the same discrete domain by subdividing the basin into triangles varying in form and size. The unstructured mesh is generated using the mesh-generation software GMSH (Geuzaine and Remacle, 2009). The numerical domain is composed of about 48 000 triangular elements having horizontal resolution varying from about 4 km in the open sea to a few metres in the river branches and the connecting channels. Vertically, the model runs in z layer configuration, with 68 layers of increasing thickness, from 1 m in the topmost layers, to 50 m in the deepest ones (below 500 m).

Figure 1(a) Unstructured numerical grid and bathymetry of the hydrodynamic model of the Danube Delta and Black Sea shelf with the red dots and the green triangles marking the sea temperature and sea level monitoring stations, respectively; (b) zoom of the grid over the Danube Delta with the blue bars near Ceatal Izmail indicating the river discharge monitoring stations; (c) zoom of the grid over the Razelm Sinoie Lagoon Systems with the red bars illustrating the considered reconnection solutions and the yellow diamonds marking the satellite SST control points. Background: © OpenStreetMap contributors 2024. Distributed under the Open Data Commons Open Database License (ODbL) v1.0.

The model bathymetry is derived by bilinearly interpolating the following datasets (all referred to the Marea Neagra Sulina vertical datum) onto the model’s numerical grid.

-

The 2022 European Marine Observation and Data Network dataset (EMODnet Bathymetry Consortium, 2022) for the shelf sea on a regular grid of arcmin, ca. 115 m grid.

-

The 2024 dataset for the Razelm Sinoie Lagoon System acquired on (mostly West-East-oriented) transects spaced 450 m apart on average and covering the whole system. The distance between two points within each transect is ∼1 m.

-

Three separate multibeam datasets (provided at a ∼1 m resolution) for the main river branches: the 2023 dataset for Chilia; the 2019 dataset for Sulina; the 2016–2017 dataset for Sf. Gheorghe. Available sparse data was used for some secondary branches and small channels.

The drag coefficient for the momentum transfer of wind has been set to a constant value of . The friction in the model is parameterized by a quadratic bottom friction expression following the Strickler formulation (Umgiesser et al., 2004, 2022). Due to the lack of data on bottom sediment characteristics, no spatial variation in bottom friction was applied, and the Strickler coefficient was uniformly set to 32 m s−1.

To investigate how the different forcing and processes influence the water mixing and renewal in the semiclosed Razelm Sinoie Lagoon System, the numerical model has been used to estimate two transport time scales: the water flushing time (WFT) and the water renewal time (WRT) (Umgiesser et al., 2014). The basin-wide WFT is defined as the theoretical time necessary to replace the complete volume of the water body with new water, assuming a hypothetical fully mixed basin, and is computed by dividing the basin volume by the volumetric water flux flowing out of the system. WRT is computed by simulating the transport and diffusion of a Eulerian conservative tracer released uniformly throughout the entire lagoon system with a concentration corresponding to 1, while a concentration of zero was imposed on the seaward and freshwater boundaries. The local WRT is considered as the time required for each cell of the RSLS to replace the mass of the conservative tracer, originally released, with new water. The ratio between the basin wide WFT and WRT can be interpreted as an index of the mixing behaviour of the basin. The reader may refer to Cucco et al. (2009) and Umgiesser et al. (2022) for a more comprehensive description of the transport time scales.

2.2 Numerical experiments

The main purpose of the model application is to reproduce the seasonal and interannual variability of the Danube Delta hydrodynamics under the influence of river discharge, heat and momentum fluxes at the water surface, salinity and sea temperature gradients and open sea forcing (sea level oscillations and currents). Moreover, the concurrence of intense atmospheric forcing, direct morphological interventions within the delta territory and freshwater inflows results in the Danube Delta being characterized by a wide range of transport phenomena. The main simulation (hereinafter referred to as the reference simulation, or REF) covers the period from 1 January 2014 to 31 December 2019, with the year 2014 considered as model spin-up time. The results are analyzed over the period 2015–2019.

The simulation was forced by 3-hourly wind, mean sea level pressure, air temperature, relative humidity, incident solar radiation, total precipitation and cloud cover fields from Copernicus European Regional ReAnalysis (CERRA; Schimanke et al., 2021) made available via the Copernicus Climate Change Service (https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.622a565a). CERRA has a horizontal resolution of 5.5 km and is forced by the global ERA5 reanalysis (Hersbach et al., 2020). The SHYFEM hydrodynamic model was forced at the lateral boundary of the Black Sea with daily sea level, current velocity, sea temperature and salinity fields from the Black Sea Physics Reanalysis made available via the E.U. Copernicus Marine Service Information (Lima et al., 2020, https://doi.org/10.25423/CMCC/BLKSEA_MULTIYEAR_ PHY_007_004, accessed on 14 June 2024). Daily observed water river discharges at Isaccea were provided by the National Institute of Hydrology and Water Management of Romania and imposed as a boundary condition for the Danube River. Water temperature at the Danube River boundary was taken from the daily results of the wflow catchment model implemented over the Danube River basin (van Gils et al., 2025).

The maximum allowable time step in the simulation was set to 60 s, and the model adopts automatic sub-stepping over time to enforce numerical stability with respect to advection and diffusion. Model outputs are saved at a daily frequency. This choice was made to limit the volume of model outputs and is justified by the fact that shorter time-scale processes are not relevant in the study area. Indeed, tides along the northwestern Black Sea coast are negligible; therefore, coastal dynamics are primarily influenced by open sea conditions, river discharge, and atmospheric disturbances with typical time scales of 1 to 10 d. Additionally, the model is forced at the boundaries of the Black Sea and the Danube River using daily datasets.

Additional what-if numerical experiments were conducted to investigate the potential effects on the lagoons' water renewal and salinisation of different reconnection solutions designed in collaboration with local stakeholders to enhance the river-lagoon-sea exchange. In the past, the lagoons were connected to the sea via several inlets, while nowadays only the Periboina and Edighiol connections remain open. The dredging of a new inlet is under consideration by local communities and authorities, as part of the activities developed under the framework of the Horizon Europe Project DANUBE4all (https://www.danube4allproject.eu/, last access: 20 October 2025). The three what-if scenarios considered in this study consisted of opening one 1.5 m depth and 70 m wide channel to connect the either the Razelm Lagoon (solutions A and B in Fig. 1c) or the Sinoie Lagoon (solution C in Fig. 1c) with the Black Sea. These reconnection solutions are located in the vicinity of previous inlets, now either closed by humans (Portiţa) or clogged (Gura Buhazului inlet, active till the beginning of the 1990s). The period, parametrization, forcing and boundary conditions considered in these what-if numerical experiments are the same as those adopted in the reference run.

2.3 Model validation

The reference simulation was validated by comparing various variables to assess the skill of the SHYFEM model in reproducing the hydrodynamics of the different water compartments within the delta. Limited spatial and temporal coverage of existing monitoring networks, along with restricted availability of freely accessible data, are critical issues in the Danube Delta. Consequently, model validation was constrained by the availability of observations during the 2015–2019 period. The available validation datasets are grouped into the following four categories:

-

In-situ river discharge: daily values are provided by the National Institute of Hydrology and Water Management of Romania for two river sections near Ceatal Izmail where the Danube River splits into the Chilia and Tulcea branches (blue bars in Fig. 1b). The Tulcea branch downstream splits into the Sulina and Sf. Gheorghe arms, but no observations were available for these branches.

-

In-situ sea level: hourly values were retrieved from the in-situ ocean thematic centre of the Copernicus Marine Service (https://marineinsitu.eu/dashboard/, last access: 10 September 2025) for stations Constanta and Mangalia (green triangles in Fig. 1a).

-

In-situ sea temperature: daily values were retrieved from the in-situ ocean thematic centre of the Copernicus Marine Service (https://marineinsitu.eu/dashboard/, last access: 10 September 2025) for BS_TS_MO stations 15360, 15480 (Constanta) and 15499 (Mangalia) (red dots in Fig. 1a).

-

Satellite Sea Surface Temperature (SST): Level 2 data derived from the Landsat-8 Thermal Infrared Sensor (TIRS) extracted over six locations within the Razelm Sinoie Lagoon to cover the spatial variability in the lagoons (yellow diamonds in Fig. 1c). The SST data are generated through the application of an atmospheric correction algorithm to the Top-Of-Atmosphere thermal radiance values from the TIRS bands (B10 and B11). This algorithm accounts for atmospheric effects such as water vapor and aerosol interference and applies a split-window technique to estimate surface temperatures with high accuracy (Barsi et al., 2003). The data, provided by the United States Geological Survey (USGS), were accessed via the Google Earth Engine platform using the LANDSAT/LC08/C02/T1_L2 dataset. To ensure data quality and reliability, scenes with cloud cover below 1 % were selected, effectively minimizing the impact of atmospheric interference. For each location, SST values were extracted at midnight using a 1×1 pixel window, corresponding to the nearest pixel to the specified coordinates. A total of 31 time frames providing 135 valid SST observations were selected in the period from 2015 to 2019.

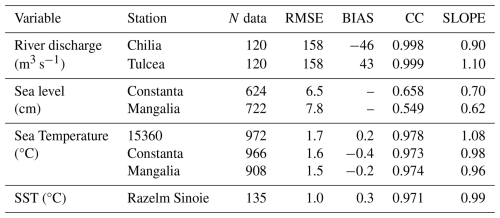

In this work, we consider the root mean square error (RMSE), the difference between the mean of simulation results and observations (BIAS), the Pearson correlation coefficient between model results and observations (CC) and the slope of the linear regression best-fit line (SLOPE) as the metrics for measuring the accuracy of the numerical results of the reference simulation. The results of the statistical analysis of river discharge, sea level and sea temperature are reported in Table 1.

Table 1Statistical analysis of simulated river discharge, sea level, sea temperature and sea surface temperature.

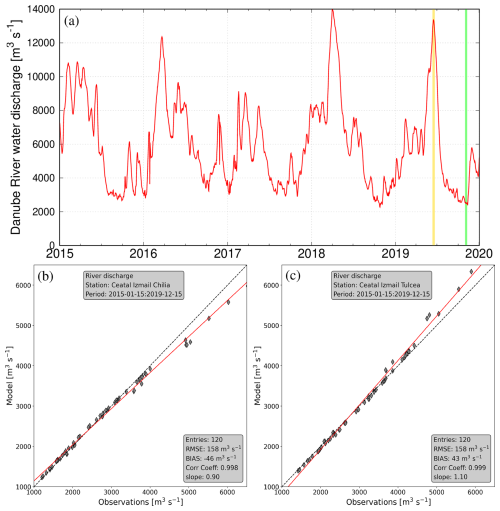

As shown in Fig. 2a, the Danube River discharge at Isaccea (the upstream river boundary in the model domain) in the period 2015–2019 varies from 2000 to 14 000 m3 s−1 with an average value of about 6000 m3 s−1. Figure 2b and c represent the scatter plots of observed and simulated river discharge through the Chilia and Tulcea river branches at Ceatal Izmail. The model well represents the total water discharge distribution in the Chilia and Tulcea branches, with a RMSE of 158 m3 s−1 and CC of 1.00 in both distributaries (Table 1). It is worth noting that the model tends to underestimate peak discharge values in Chilia and overestimate them in the Tulcea, as indicated by the slopes of the linear regression best-fit lines: 0.90 for Chilia and 1.10 for Tulcea. The underestimation at Chilia coincides with situations of overestimation at Tulcea. The inconsistency during flood events is likely attributable to the model's inability to correctly reproduce the river overflow into the surrounding floodplains.

Figure 2Danube River water discharge timeseries (a) and scatter plots of observed and modelled river discharge in the Chilia (b) and Tulcea (c) river branches. The gold and green bars in panel (a) indicate the flood and drought conditions considered in Fig. 5b and c. The gray diamonds and the red lines in panels (b) and (c) represent the scatter data and the line of best fit, respectively.

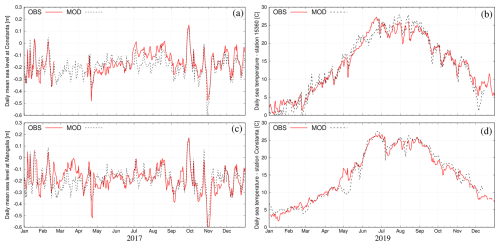

We report in Fig. 3 the daily averaged time series of modelled and observed sea levels for year 2017 at the coastal stations Constanta and Mangalia located along the Romanian coast (green triangles in Fig. 1a). Due to an unknown reference datum, the sea level time series were de-biased prior to analysis. The model can reproduce the variability of the daily mean sea level in the year 2017 including major sea level events associated with stormy periods of typically 1–10 d. The model is slightly underestimating sea levels in some periods (e.g., Constanta in July–August and Mangalia in March). The statistical analysis revealed that RMSE and CC in Constanta and Mangalia are 6.5 cm and 0.66, and 7.8 cm and 0.55, respectively (Table 1). It must be noted that the performance of the coastal model in reproducing sea levels is strongly determined by the open boundary conditions, therefore any discrepancy in the sea level simulated by the Black Sea Physics Reanalysis is propagated to the coast.

Figure 3Observed (red line) and simulated (black dashed line) sea levels at Constanta (a) and Mangalia (c), and sea temperature at station 15360 (b) and Constanta (d).

As presented in the right panels of Fig. 3 (illustrated for the year 2019 at stations 15360 and Constanta), the numerical model captures correctly the seasonal variability as well as the short-term fluctuations of the sea temperature in the investigated area. The statistical analysis of the simulated sea temperatures revealed that RMSE is between 1.5 and 1.7 °C and the CC is always above 0.97 (Table 1).

Satellite derived data demonstrate that sea surface temperature in RSLS varies strongly over the 2015–2019 period with values ranging from 0 °C in winter to 28 °C in summer. Spatially SST in the lagoons has a small spatial variability with difference among stations less than 1.5 °C. To assess the model's performance, we extracted water temperature values from the simulation results in the surface layer at the location and time corresponding to the satellite SST data. The statistical comparison between model results and observations reported in Table 1 (RMSE = 1 °C, BIAS = 0.3 °C, CC = 0.97, slope = 0.99) demonstrated that SHYFEM can represent well both the spatial and temporal variability revealed by satellite data.

The validation analysis demonstrates that our SHYFEM model application correctly reproduces hydrodynamics in the different water compartments of the Danube Delta. The model validation could be further enhanced with the availability of additional future observations, particularly river discharge and salinity data. In light of these limitations, there is a clear need for an transnational integrated observation system that combines all available monitoring networks managed by academic and research institutions, national and regional environmental protection agencies and local communities. In this context, the pan-European Research Infrastructure DANUBIUS-RI (the International Centre for Advanced Studies on River-Sea Systems, http://www.danubius-ri.eu/, last access: 25 October 2025) is building integrated infrastructures – made of observational networks, modelling and forecasting systems, and living laboratories – on ten of the major European river-sea systems, one of which is the Danube Delta (De Pascalis et al., 2025).

The modelling results are presented and analyzed separately for the main water compartments forming the delta: the river network (Sect. 3.1), the coastal sea (Sect. 3.2) and the lagoons (Sect. 3.3). The assessment of the impact of the different lagoon-sea reconnection interventions is included in Sect. 3.3.1.

3.1 Water division in the river network of the delta

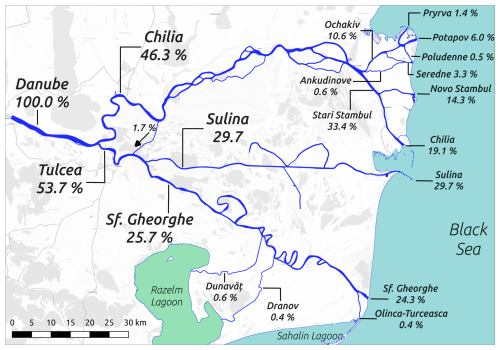

The Danube Delta's river network comprises a highly complex system of hundreds of natural and artificial channels, streams, marshes, and lakes, whose morphological complexity exceeds the resolution capabilities of the current model implementation. The model was configured to represent only the most hydraulically significant watercourses, enabling the estimation of water discharge distribution among the principal river branches. Here, the water fluxes were extracted for several river sections and averaged over the simulation period (2015-2019) to estimate the relative runoff (in %) of each branch with respect to the average Danube River discharge imposed at the open boundary of Isaccea (6000 m3 s−1). The average water division values are reported in Fig. 4. Unless otherwise specified, the reported values refer to averages over the whole 2015–2019 simulation period.

Figure 4Modelled average water diversion within the Lower Danube River downstream of Isaccea. Background: © OpenStreetMap contributors 2024. Distributed under the Open Data Commons Open Database License (ODbL) v1.0.

The Danube discharge firstly subdivides into the Chilia and Tulcea branches, which have an average fraction of 46.3 % and 53.7 %, respectively, this well reproducing the observed distribution. The Chilia branch in the northern part of the delta is characterized by a complex network of secondary arms that depart and rejoin to the main channel. 20 km from the sea, Chilia bifurcates into the Ochakiv (also known as Ochakov) channel (10.6 %), that downstream originates four mouths, and the Stari Stambul Vechi (33.4 %) channel, which splits into Novo Stambul (14.3 %) and Chilia (19.1 %) outflows. The 18 km long Tulcea distributary bifurcates into the Sulina branch, carrying almost 29.7 % of the Danube waters to the sea, and the Sf. Gheorghe (25.7 %) branch flowing through the southern part of the delta. A small fraction of the Sf. Gheorghe discharge is captured by the Dunavǎţ (0.6 %) and Dranov (0.4 %) canals that flow down into the Razelm Lagoon. Just before flowing into the Black Sea, the Sf. Gheorghe branch separates in the Olinca-Turceasca channel (0.4 %), flowing into the Sahalin Lagoon (0.4 %), and the main mouth (24.3 %).

We point out that the model estimate of the water division into the multiple branches of the delta is very sensitive to the accuracy of the morphological and bathymetric datasets used to create the numerical grid, which – due to lack of observations as mentioned in Sect. 2.3 – has been validated only for the upper part of the delta river network. However, the simulated distribution of the Danube's mean discharge between the Chilia, Sulina and Sf. Gheorghe (46.3 %, 29.7 % and 25.7 %, respectively) is similar to the results reported by Nichersu et al. (2025) (45 %, 34 % and 21 %, respectively). It is worth noting that the river discharge division among the main branches has been altered by human interventions (Constantinescu et al., 2023; Bloesch et al., 2025).

3.2 Spatial and temporal variability of coastal dynamics

The dynamics in coastal areas at the river-sea interface is generally determined by the mixing processes induced by the interaction of river outflow and coastal currents, mainly driven by the open sea circulation and wind (Garvine, 1995; Fong and Geyer, 2002; Bellafiore et al., 2019). Along the coast, these processes create distinct hydrodynamic patterns, the so-called river plumes, having thermohaline characteristics and buoyancy that allow to distinguish them from seawater. The river plume extension delineate the coastal Region Of Freshwater Influence (ROFI; Simpson et al., 1993).

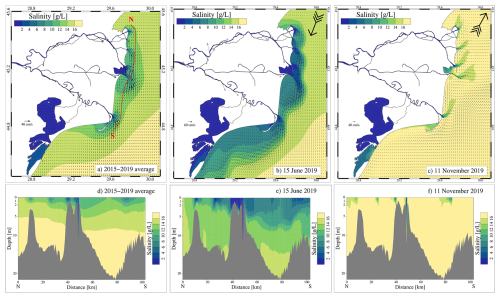

Off the coast of the Danube Delta, the overall coastal circulation – averaged over the entire period of 5 years – reveals distinct freshwater plumes formed by the various branches of the multi-mouth delta. The shape and size of these plumes are influenced by both the volume of water discharged from each river branch and the specific features of the coastline (Fig. 5a). Indeed, the largest plume is found south of the Sulina mouth, where the 8 km long artificial jetty enhances the offshore spread of riverine waters and creates a well-defined recirculation structure. It has to be noted that this plume is reinforced by the freshwater discharged from the nearby Chilia mouth. Well-defined plumes can be also recognized out of the Sf. Gheorghe, Novo Stambul and Potapov mouths. On average, the ROFI associated with the Danube River extends for about 15 km offshore the river mouths. As illustrated in Fig. 5d, the freshwater inputs determine a stratified water column along the coast, with Black Sea waters (defined here as having salinity higher than 16 g L−1) located on average below 5 to 10 m from the surface. A low-intensity (<0.1 m s−1) southward current characterize the shelf area which is also influenced by the long-shore dynamics induced by the rivers flowing along the northwestern Black Sea coast (Southern Bug, Dniestr and Dniepr; Miladinova et al., 2020). The lagoon system is on average characterized by very weak currents (in the order of a few cm s−1) and salinity ranging from 1 to 4 g L−1, with the Sinoie Lagoon being saltier than the Razelm lagoon due to the inflow of marine waters through the Edighiol and Periboina inlets.

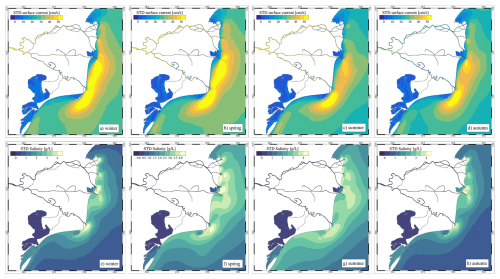

Figure 5Surface salinity and current velocity maps, and N-S salinity transects: (a, d) average values over the 2015–2019 period; (b, e) instant values on 15 June 2019; (c, f) instant values on 11 November 2019. The arrows in the top right corner of panels b and c indicate the wind direction.

The hydrodynamics of the whole area is strongly variable in time and space depending on Danube River discharge and other forcing (e.g., wind, heat fluxes, long-shore currents). As examples of a such a strong variability, we analysed the dynamics in the investigated area during two events having different hydro-meteo-marine conditions: (1) a summer event (15 June 2019) with peak river discharge (13 000 m3 s−1) and northerly wind (Fig. 5b and e), and (2) an autumn event (11 November 2019) with low river discharge (2400 m3 s−1) and southerly wind (Fig. 5c and f). The high freshwater input during peak Danube River discharge extends ROFI far offshore and to the south, determining a reduction in salinity over a large portion of the coastal area and the enhancement of the southward surface coastal currents up to 0.6 m s−1 (Fig. 5b). During peak river discharge and northerly wind conditions, vertical mixing processes near the coast occupy the whole water column (Fig. 5e). On the contrary, during low river discharge, the surface coastal dynamic is mainly driven by the wind. The autumn event presented in Fig. 5c is characterized by a general northward surface transport of saline waters with the ROFI limited to river plumes extending north-eastward for a few km from the river mouths. During such an event, the water column in front of the delta is well mixed except for a 2 m surface layer (Fig. 5f).

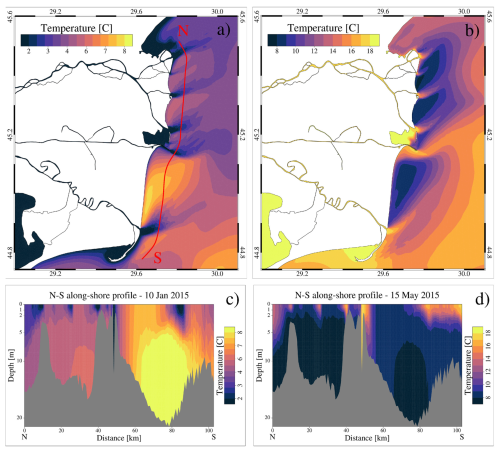

Figure 6Maps of sea surface temperature and north-to-south alongshore transects of sea temperature under southerly wind conditions during winter (10 January 2015; panels a and c) and spring (15 May 2015; panels b and d). The transect location is indicated with a red line in panel (a).

The analysis of the sea temperature results during events of southerly wind revealed the presence of small scale near-shore patterns located between the river mouths and having thermo-haline characteristics different from the surrounding areas (Fig. 6). The vertical alongshore sea temperature transect presented in Fig. 6c and d indicate an upwelling-driven transport of offshore marine waters from deeper layers to the coastal zone, enhancing mixing between open sea and riverine waters. The presented analysis indicates that these particular features are generated by upwelling processes induced by the action of southerly winds blowing along the coastline and interacting with the river outflow.

To analyze the temporal variability of coastal dynamics, the model results were processed to compute the seasonal standard deviation (hereinafter STD) using all daily values from the corresponding season (winter = DJF, spring = MAM, summer = JJA, autumn = SON) during the period 2015–2019. The surface current variability is higher in winter (Fig. 7a) and spring (Fig. 7b) with STD values above 0.5 m s−1 in a coastal strip extending from the Sulina mouth down to the end of the Sahalin spit. During summer (Fig. 7c) and autumn (Fig. 7d) the highest current velocity variability is found south of the Sf. Gheorghe mouth. The highest variability in the surface salinity is found during spring (Fig. 7f) and summer (Fig. 7g) months with STD values above 3 g L−1 characterizing large areas in front of each river mouth and a large coastal band south of the delta. The freshwater discharged by the different branches determine a similar salinity standard deviation pattern in winter (Fig. 7e) and autumn (Fig. 7h). These findings reflect the seasonal variability in the strength of the main drivers: (i) the Danube River discharge, which usually peaks in spring or early summer, while drought conditions are generally observed in autumn (Fig. 2a); and (ii) wind forcing (both northerly and southerly), which tends to be stronger in winter and autumn (Bajo et al., 2014).

3.3 Lagoons' water exchange, mixing and renewal capacity

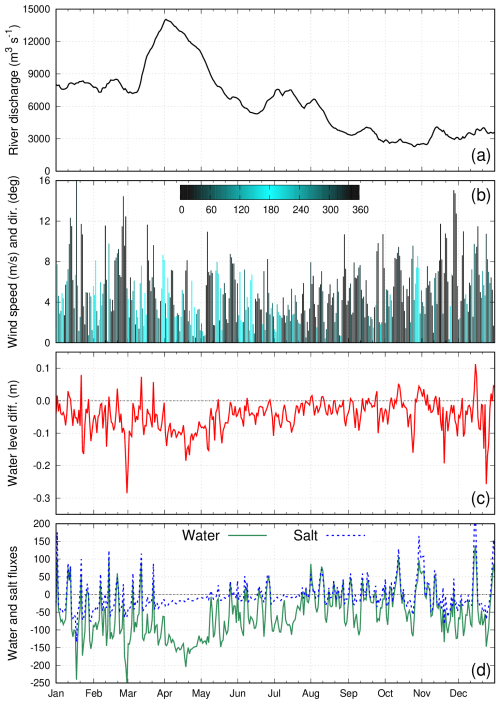

The Razelm Sinoie Lagoon System is a transitional coastal environment connected to the Danube River and the Black Sea. The lagoon's circulation is influenced by the freshwater inflow, the coastal sea level and the wind action over the system. Such dynamics are well illustrated in Fig. 8, which presents daily values from 2018 for Danube River discharge, wind speed and direction in the RSLS, sea-lagoon (Sinoie) water level differences, and total water and salt fluxes through the Edighiol and Periboina inlets.

Figure 8(a) Daily values for the year 2018 of Danube River discharge, (b) wind speed and direction (0° means a northerly wind and 180° indicates a southerly wind) in the RSLS, (c) simulated sea-lagoon (Sinoie) water level difference, (d) simulated sea-lagoon water (in m3 s−1) and salt (in 10−1 kg s−1) fluxes. Positive values of water and salt fluxes indicate inflow into the lagoons, while negative values indicate outflow from the lagoon to the sea. Model results are from the reference simulation.

The water level in the Sinoie Lagoon is generally higher than in the coastal area particularly during high river discharge conditions (e.g., from March to May 2018). However, the model results show high temporal variability induced by the wind action over the lagoons and the coastal sea. It must be noted that the water flux is not linearly dependent on the water level gradients confirming that the flow between the lagoon and the sea is limited by the transport capacity of the Edighiol and Periboina inlets (as occurring at the end of February 2018; Fig. 8c and d). A two-layers flow in the Edighiol inlet may occur when the lagoon-sea water level gradient is small (in the order of a few of cm).

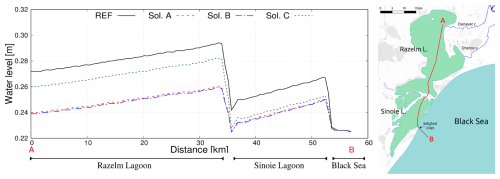

The freshwater inflow from the Dunavǎţ and Dranov canals creates, on average, a persistent water level gradient from Razelm Lagoon to Sinoie Lagoon and the adjacent coastal sea (black line in Fig. 9). The water level jumps between the two lagoons and between the Sinoie Lagoon and the open sea indicate that the water exchange between the different water bodies is limited by the transport capacity of the narrow and shallow connecting canals (Canal 2, Canal 5, Edighiol and Periboina inlets). The internal average north-to south sea level gradient found into both lagoons is determined by the dominant winds from north-easterly direction.

Figure 9Average (over 2015–2019 period) water levels along the AB transect crossing the Razelm Sinoie Lagoon Systems indicated with a red line in the right panel. Background: © OpenStreetMap contributors 2024. Distributed under the Open Data Commons Open Database License (ODbL) v1.0.

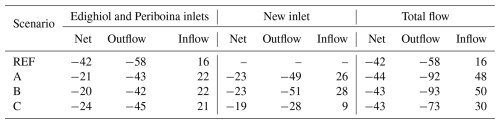

The RSLS has an average water volume of about 1300 million m3 and receives 40 and 22 m3 s−1 of freshwater from the Dunavǎţ and Dranov canals, respectively. This excess water entering the lagoons is primarily discharged into the Black Sea via the Edighiol and Periboina inlets, resulting in a average seaward flow of 58 m3 s−1. The average inflow of marine water into the RSLS amounts to 16 m3 s−1. Evaporation over the lagoon system exceeds precipitation resulting in a net loss of 20 m3 s−1. The lagoons receive a total water flux of 78 m3 s−1 from the sea and the river. The average fluxes are reported in Table 2.

Table 2Average water fluxes (in m3 s−1) between the lagoons and the sea via the Edighiol and Periboina inlets and the new inlets (positive values indicate inflow into the lagoons, while negative values indicate outflow from the lagoon to the sea).

The basin-wide WFT is 193 d. The flushing time estimate was used to determine the duration of the water renewal time simulations. In this work, we performed five one-year-long replicas of WRT starting the simulations at the beginning of each year. The dispersion and dilution of the tracer initially released into the lagoons (see Sect. 2.1) are determined by the inflow of new water and internal mixing processes that in the shallow lagoon system are mainly induced by the wind. The average (over the five replicas) basin-wide WRT is 241 d (minimum = 181 d in 2018; maximum = 333 d in 2017; standard deviation = 63 d) for the RSLS, thus revealing a mixing efficiency (determined as the ratio between WFT and WRT) of 0.8.

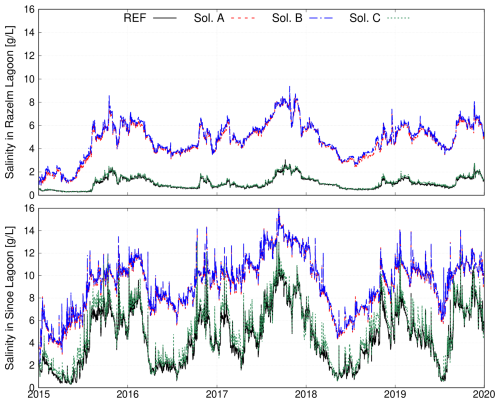

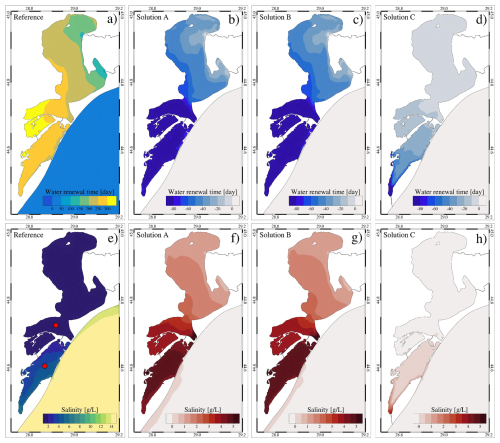

The spatial and temporal variability of river, ocean and meteorological conditions affects the river-lagoon-sea fluxes as well as the internal mixing in the lagoons, and consequently the WRT computation. Indeed, the difference in WRT across the different years primarily reflects the freshwater input into the lagoons that mainly drives the river-lagoon-sea fluxes and therefore the flushing of the lagoon waters. Indeed, the minimum (181 d) and maximum (333 d) basin-wide WRT values are found in the flood (2018) and drought (2017) years, respectively (Fig. 2). A secondary, but not negligible, role is played by the wind which in 2018 was characterized by frequent and intense Northerlies that enhanced internal mixing and favored the outflow from the lagoon towards the sea. Spatially, a marked east-to-west WRT gradient (from 50 to more than 300 d) is evident in the RSLS, with the Razelm Lagoon having lower values than the Sinoie Lagoon (Fig. 10a). This is because the new (fresh) waters enter the Razelm Lagoon from the Dunavǎţ and Dranov canals and are subsequently mixed and transported to the Sinoie Lagoon. The input of marine waters through the Edighiol and Periboina inlets has a limited effect on the local WRT. Salinity shows limited variability across the RSLS, with values ranging from 1 to 8 g L−1. The highest values are observed in the area of Sinoie Lagoon, near the Edighiol and Periboina inlets (Fig. 10e).

Figure 10Average water renewal time and salinity over the Razelm Sinoie Lagoon System for the reference simulation (as absolute values) and the reconnection scenarios A, B and C (as difference with respect to the reference run). The red dots in panel (e) indicate the location of the two control points where the salinity timeseries were extracted (Fig. 11).

3.3.1 Assessment of the potential impact of what-if lagoon-sea reconnection scenarios

As illustrated in previous section, the RSLS is a large and shallow water body separated from the sea by narrow sandy barriers and with limited renewal capacity. In this study, we use the modelling setup for the period 2015–2019 to evaluate the effects of several reconnection solutions (Fig. 1c) on the river-lagoon-sea exchange, water renewal time and salinization. The numerical model results of the different simulations were processed to estimate the lagoon-sea water exchange through the inlets (the two existing and the newly designed) and the values are reported in Table 2. The reference run presented in previous sections is used as a basis for comparison for the what-if scenarios.

Opening a new inlet has a significant effect on the lagoon hydrodynamics altering the water budget of the basin and the fluxes through the existing Edighiol and Periboina inlets, which generally resulted to be enhanced inflow into the lagoon and reduced outflow out of the lagoon (Table 2). The net flow between the lagoons and the sea is not significantly altered (about 40 m3 s−1), being mostly determined by the river inflow into the lagoon. However, opening a new inlet increases up to four times the total inflow of marine waters into the lagoon with the respect of the reference simulation, with the solutions planned for the Razelm Lagoon (A and B) having a higher effect on the fluxes than the ones designed in the Sinoie Lagoon (C).

Connecting the Razelm Lagoon with the Black Sea with solutions A and B does not only allow the inflow of marine waters but also changes the water level of the two basins (red and blue lines in Fig. 9) decreasing the water exchange between the two lagoons and the outflow via the existing inlets (Table 2). On the contrary, solution C (green line in Fig. 9) affects water levels mostly in the Sinoie Lagoon and the fluxes with the Black Sea but has a limited impact on the Razelm basin.

Because of these changes in the water level and fluxes, the water renewal capacity and the salinity increase (shorter water renewal time values). The average WRTs decrease to 191, 190 and 230 d in scenarios A, B and C, respectively. The spatial distributions of WRT illustrated in Fig. 10 clearly reflect the changes in the lagoon-sea fluxes. Therefore, solutions A (Fig. 10b) and B (Fig. 10c), are the ones determining a more significant decrease in the water renewal times, especially in the southern part of the Razelm Lagoon and in the Sinoie Lagoon where the WRT values decrease by up to 80 d with respect to the REF simulation. Solution C (Fig. 10d) has a moderate effect on WRTs, which is anyway limited to the southern past of the Sinoie Lagoon.

The augmented inflow of marine waters through the existing and the new inlets determines a general increase in salinity in the southern part of the lagoons. The highest salinity changes with respect to the REF simulation (Fig. 10e) are found in scenarios A (Fig. 10f) and B (Fig. 10g) in the Sinoie Lagoon where the average salinity increases to more than 5 g L−1. As for the water renewal times, solution C (Fig. 10h) has a limited effect on salinity.

To investigate more details of the opening effects on the salinity, we extracted from the simulation results the timeseries in two control stations in the Razelm and Sinoie lagoons identified with red dots in Fig. 10e (Fig. 11). Solutions A and B have very similar effects on salinity which fluctuates between 2 and 8 g L−1, and between 6 and 16 g L−1 in the Razelm and Sinoie lagoons, respectively. Lastly, solution C has an almost negligible (<1 g L−1) effect on salinity in both lagoons.

The Danube Delta, like many other coastal systems at the river-sea interface, is composed of several interconnected water bodies (river branches, coastal lakes, lagoons, shelf sea) having different physicochemical characteristics and influencing each other (Passalacqua, 2017). The exchanges of water between the different interconnected water compartments of the delta are regulated by barotropic and baroclinic processes driven by the forcing acting on the area: upstream river discharge, wind stress, heat fluxes, open sea conditions. Here we interpret how cross-scale processes and water mass exchanges between river branches, lagoons, and the coastal sea shape hydrodynamics in the Danube Delta, and we assess how these findings generalize to other river-sea systems. Finally we review the implication of the reconnection solutions on the connectivity between the different water bodies.

The water flow in the river is predominantly governed by advection, and the redistribution of water over the distributaries is mainly determined by the branch geometry and hydraulic roughness. Nevertheless, the distribution of water discharge can vary considerably under different flow regimes (Maicu et al., 2018; Constantinescu et al., 2023). Our simulation results indicate that the standard deviation of the relative discharge among the Danube Delta branches remains below 0.7 %. Such a low temporal variability can be partially attributed to the exclusion of the delta floodplain system from the computational domain.

An accurate representation of water distribution within the delta's river network, along with its temporal variability, is crucial for correctly reconstructing the freshwater input into the Black Sea, and consequently, the river plumes and coastal dynamics. Indeed, in the coastal area in front of the Danube Delta, the presence of multiple freshwater outlets generates multiple buoyant fluxes that interact laterally modulating coastal mixing (Fig. 5). This type of coastal dynamics is common among many of the world's major river deltas – such as the Mississippi and the Nile (Horner-Devine et al., 2015) – as well as in coastal regions where multiple river mouths are located in close proximity (Warrick and Farnsworth, 2017). The interaction between stratified waters belonging to river plumes and the wind force determines complex coastal dynamics. During northerly wind conditions, the freshwater plumes are constrained close to the coast and advected to the south. Southerly winds that promote coastal upwelling cause the plumes to thin and be advected offshore due to Ekman transport (Fong and Geyer, 2001). During these events, upwelling – rather than horizontal advection – generates small-scale nearshore patterns between the river mouths, characterized by surface temperatures that are either warmer or colder than offshore waters, depending on the season (Fig. 6). Similar patterns were found by Bellafiore et al. (2019) in front of the Po River Delta.

In addition to the river influence on the coastal dynamics, during drought periods marine waters can intrude the lower part of the river course, altering the water's physicochemical properties. Such a phenomenon, known as saltwater intrusion, is driven by a three-dimensional estuarine dynamics that determines freshwater flowing on the surface layers and the salt wedge intruding along the riverbed (Valle-Levinson, 2010). According to the reference simulation results, marine waters enter up to 20 km upstream from the mouth in the Chilia and Sulina branches, and up to 7 km upstream from the Sf. Gheorghe mouth. While saltwater intrusion poses a serious threat to several coastal areas compromising freshwater supplies for agriculture and human use (Li et al., 2025), it has not yet been reported as a major issue in the Danube Delta. The situation is predicted to worsen in the near future due to sea level rise (van de Wal et al., 2024) and decreasing summer runoff (Probst and Mauser, 2023; Stolz et al., 2025).

Capturing the spatial and temporal variability of water distribution in the delta's river network is essential for accurately modelling the amount of freshwater entering the Razelm Lagoon via the Dunavǎţ and Dranov canals. This surplus of water drives the long-term net water transport in the RSLS, which is mainly barotropic and flows from the Danube River to the Razelm Lagoon, then to the Sinoie Lagoon (via canals 2 and 5), and finally to the open sea (via the Edighiol and Periboina inlets). While the water flow from the river to the lagoons is unidirectional, a bidirectional flow characterizes the water exchange between the lagoons and the Black Sea. Marine waters flow into the lagoon when sea level exceeds the lagoon's water level. This inflow tipically occurs during autumn and winter, especially under drought and windy conditions. As a result, salinization events of the lagoon environments are sporadic and have a general duration of a few days. The salt content entering the Edighiol and Periboina inlets is advected and diluted in the Sinoie Lagoon and sporadically reaches the Razelm basin (Fig. 8a). Even though river and marine waters enter the lagoon systems, the water masses in the RSLS, as in many shallow coastal water systems (Umgiesser et al., 2014), are generally vertically well mixed due to the wind action.

The water exchanges with the river and the sea regulate the renewal capacity of the lagoons, while wind stress modulates internal mixing. Due to the limited degree of water exchange, the Razelm-Sinoie lagoons can be classified as a choked water body, according to Kjerfve (1986). Wind stress actively promotes water circulation within the lagoons, making the RSLS a well-mixed water body, according to Umgiesser et al. (2014).

The Danube Delta, as many other coastal transitional systems (Maselli and Trincardi, 2013), has been heavily affected by human interventions (Nichersu et al., 2025, and references therein). Among river-sea systems, lagoons are highly productive areas that support numerous industrial, commercial, and recreational activities (Pérez-Ruzafa et al., 2019). Similarly, the RSLS is subject to economic interests related to fisheries, agriculture, and water-based tourism. Numerical models have been widely used to evaluate the impact of anthropogenic interventions on coastal environments throughout the simulation of what-if scenarios (Ferrarin et al., 2013; Umgiesser, 2020; Hariharan et al., 2023; Kolb et al., 2022, among others). In the RSLS, efforts to enhance ecological status and improve water circulation have prompted exploration into the potential impacts of creating a new inlet to strengthen the lagoon's connection with the sea. The findings presented in Sect. 3.3.1 suggest that even a localized morphological modification can significantly influence the overall hydrodynamics of the lagoon system. Introducing a new inlet in the Razelm Lagoon (scenarios A and B) leads to a 20 % reduction in the RSLS renewal time, which helps mitigate stagnation and enhances ecological conditions. However, it also results in elevated salinity levels up to 9 and 16 g L−1 in the Razelm and Sinoie lagoons, respectively. While fisheries and tourist activities would benefit from this intervention, the increased salinization of the lagoon's waters poses a considerable risk to agricultural freshwater resources. In contrast, the impact of solution C on WRT and salinity is limited to the southern part of the Sinoie Lagoon. To help local authorities and communities manage these issues, the model will be used to explore lagoon-sea reconnection solutions with flow regulation based on seasonal and meteo-marine conditions.

This work presents the first cross-scale hydrodynamic model implementation covering the entire Danube Delta to investigate the river-sea continuum. To study the hydrodynamic processes driving water exchange and connectivity among the various interconnected water compartments of the delta, the 3D unstructured hydrodynamic SHYFEM model was applied to a domain representing the delta river network, the Razelm Sinoie Lagoon System, and part of the western Black Sea shelf. The variable model resolution is of fundamental importance for reproducing the complex morphology of the Danube Delta and achieving a seamless transition across spatial scales, from river branches to the coastal sea. Compared to standalone hydrological and ocean models, the river-sea continuum approach is essential to accurately represent the non-linear and bidirectional interactions among the various water compartments of the delta. In particular, cross-scale modelling is essential in the coastal sea near the river mouths to accurately capture plume dynamics. By contrast, most regional models of the Black Sea (e.g., Lima et al., 2020; Miladinova et al., 2020) employ coarse resolutions (greater than 2 km) and simplified representations of river inputs, which are inadequate for describing the complex coastal circulation patterns revealed in this study.

A multi-year (2015–2019) hindcast simulation was performed using observational data and reanalysis fields as forcings. The simulation results enabled the quantification of riverine discharge distribution among the major branches (Chilia: 46.3 %, Sulina: 29.7 %, and Sf. Gheorghe: 25.7 %) and the distributaries of the delta river network, thereby characterizing the relative significance of the nine river mouths. Such a detailed description of the freshwater outflow into the Black Sea enabled the investigation of spatial and temporal variability in the main oceanographic processes occurring offshore of the Danube Delta. River inputs create a stratified water column along the coast, with Black Sea waters typically found at depths greater than 5 to 10 meters below the surface. The region of freshwater influence is shaped by the multiple buoyant fluxes forming coalescing river plumes, and alongshore winds. The predominant northerly wind regime sustains a southward coastal current that enhances the southward propagation of the freshwater plumes. Southerly wind conditions favour coastal upwelling, which enhances the offshore propagation of river plumes and creates entrapped marine water regions between them.

On average, approximately 2000 million m3 of water per year flows from the Danube River into the Razelm Lagoon via the Dunavǎţ Dranov canals. This input of freshwater creates a north-to-south water level gradient in the Razelm Sinoie Lagoon System, which determines a barotropic flow from the Razelm Lagoon to the Sinoie Lagoon and ultimately to the Black Sea. The inflow of marine waters into the Sinoie Lagoon occurs sporadically during southerly wind events that induce a positive sea-to-lagoon water level gradient. Water exchanges with the Danube River and the Black Sea determine the flushing capacity of the RSLS, while wind is the primary driver of horizontal and vertical mixing of the lagoon waters. These processes are accounted for in the simulation of a passive Eulerian tracer, which allowed the estimation of the water renewal time in this interconnected coastal environment. The average water renewal time of the RSLS is 241 d, with marked interannual variability mainly driven by freshwater input into the lagoons and the wind conditions.

Lastly, the numerical model was used to assess the potential impacts of opening a new inlet (with three different configurations) designed to improve the river-sea-lagoon connectivity. Opening a third connection to the Black Sea would enhance water exchange between the RSLS and the sea, thereby increasing water flushing and reducing the water renewal time to as little as 190 d (solutions B). At the same time, the augmented inflow of marine waters significantly raised salinity in the southern and central parts of the RSLS by up to 5 g L−1 compared to the reference situation. We demonstrated that this modelling system is a powerful tool for efficiently evaluating the effects of human interventions in the coastal environment.

The applied numerical model and implementation approach are easily exportable to other river-sea environments and can be further developed to support decision-making. An operational version of the Danube Delta model is currently under implementation to provide forecasts that enhance awareness and preparedness for weather-related risks. The simulated what-if scenarios and forecasting system will form the core of a digital twin of the Danube Delta.

The community SHYFEM hydrodynamic model is open source (GNU General Public License as published by the Free Software Foundation) and freely available through GitHub at https://github.com/georgu/shyfemcm-ismar (last access: 10 September 2025) and https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17721804 (Umgiesser et al., 2025).

This study has been conducted using the following public available datasets: the Black Sea Physics Reanalysis (https://doi.org/10.25423/CMCC/BLKSEA_MULTIYEAR_PHY_ 007_004; Lima et al., 2020); the Copernicus European Regional ReAnalysis (https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.622a565a; Schimanke et al., 2021); the 2022 European Marine Observation and Data Network bathymetry (https://doi.org/10.12770/ff3aff8a-cff1-44a3-a2c8-1910bf109f85; EMODnet Bathymetry Consortium, 2022); in situ sea level and sea temperature data (https://marineinsitu.eu/dashboard/, last access: 25 October 2025); the Danube River temperature data generated by the Black Sea Catchment model developed by Deltares in the EU project DOORS (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15675190; van Gils et al., 2025); The following datasets are not public available and can be requested to the mentioned authorities: the National Institute of Hydrology and Water Management of Romania for the Danube River discharge data; the University of Stirling (UK) for satellite sea surface temperature data; GeoEcoMar (RO) for the 2024 Razelm Sinoie Lagoons, the 2019 Sulina branch and the 2016–2017 Sf. Gheorghe branch bathymetric datasets.

CF conceived the idea of the study with the support of AS. ID and CF collected the bathymetric and validation data sets. AS designed the reconnection solution to improve river-lagoon-sea hydrological connectivity. CF and APH performed the numerical simulations and analysed the results. All authors discussed, reviewed and edited the manuscript.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

The authors wish to thank the National Institute of Hydrology and Water Management of Romania for providing river discharge data at Ceatal Izmail; the European Union's Horizon 2020 DOORS project, grant agreement number 101000518, in particular Jos Van Gils, Hélène Boisgontier and Sibren Loos (Deltares, NL) for providing Danube River temperature data (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15675190; van Gils et al., 2025); Nagendra Jaiganesh Sankara Narayanan, Andrew Tyler and Evangelos Spyrakos from the University of Stirling (UK) for providing satellite sea surface temperature data; the Lower Danube River Administration for providing 2023 bathymetric data for Chilia Branch; and Albert Scrieciu from GeoEcoMar (Romania) for providing bathymetry and river discharge data. The bathymetry of the Razelm Sinoie was updated during 2024 activities in the Romanian UESFISCDI “DANUBE4all Support” project (77PHE/ 2024). This study was conducted as part of the DANUBE4all (Restoration of the Danube River Basin for ecosystems and people from mountains to coast; ID 101093985; https://www.danube4allproject.eu/, last access: 25 October 2025) and iNNO SED (iNNOvative SEDiment management in the Danube River Basin; ID 101157360; https://innosed.eu/, last access: 25 October 2025) projects funded by the European Union under EU Mission “Restore our Ocean and Waters”. This work is part of the activities of the scientific community that is building the pan-European Research Infrastructure DANUBIUS-RI – The International Centre for Advanced Studies on River-Sea Systems (http://www.danubius-ri.eu/, last access: 25 October 2025).

This research has been supported by the EU HORIZON EUROPE European Research Council (grant nos. DANUBE4all, 101093985 and iNNO SED, 101157360).

This paper was edited by John M. Huthnance and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Androsov, A., Fofonova, V., Kuznetsov, I., Danilov, S., Rakowsky, N., Harig, S., Brix, H., and Wiltshire, K. H.: FESOM-C v.2: coastal dynamics on hybrid unstructured meshes, Geosci. Model Dev., 12, 1009–1028, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-12-1009-2019, 2019. a

Bajo, M., Ferrarin, C., Dinu, I., Stanica, A., and Umgiesser, G.: The circulation near the Romanian coast and the Danube Delta modelled with finite elements, Cont. Shelf Res., 78, 62–74, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csr.2014.02.006, 2014. a, b

Barsi, J., Barker, J., and Schott, J.: An atmospheric correction parameter calculator for a single thermal band earth-sensing instrument IGARSS 2003, in: Proceedings of the 2003 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IEEE Cat. No. 03CH37477), 5, 3014–3016, 2003. a

Bellafiore, D., Mc Kiver, W., Ferrarin, C., and Umgiesser, G.: The importance of modeling nonhydrostatic processes for dense water reproduction in the southern Adriatic Sea, Ocean Model., 125, 22–28, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocemod.2018.03.001, 2018. a

Bellafiore, D., Ferrarin, C., Braga, F., Zaggia, L., Maicu, F., Lorenzetti, G., Manfè, G., Brando, V., and De Pascalis, F.: Coastal mixing in multiple-mouth deltas: a case study in the Po Delta, Italy, Estuarine Coastal Shelf Sci., 226, 106254, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2019.106254, 2019. a, b

Bellafiore, D., Ferrarin, C., Maicu, F., Manfé, G., Lorenzetti, G., Umgiesser, G., Zaggia, L., and Valle-Levinson, A.: Saltwater intrusion in a Mediterranean delta under a changing climate, J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans, 126, e2020JC016437, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020JC016437, 2021. a

Bloesch, J., Lenhardt, M., and Ionescu, C.: Chapter 8 – Hydromorphological alterations and overexploitation of aquatic resources, in: The Danube River and The Western Black Sea Coast, edited by: Bloesch, J., Cyffka, B., Hein, T., Sandu, C., and Sommerwerk, N., Ecohydrology from Catchment to Coast, 147–164, Elsevier, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-443-18686-8.00001-9, 2025. a

Bricheno, L. M., Wolf, J., and Islam, S.: Tidal intrusion within a mega delta: An unstructured grid modelling approach, Estuarine Coastal Shelf Sci., 182, 12–26, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2016.09.014, 2016. a

Burchard, H. and Petersen, O.: Models of turbulence in the marine environment – a comparative study of two equation turbulence models, J. Mar. Syst., 21, 29–53, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-7963(99)00004-4, 1999. a

Chen, C., Liu, H., and Beardsley, R.: An unstructured grid, finite-volume, three-dimensional, primitive equations ocean model: application to coastal ocean and estuaries, J. Atmos. Ocean. Tech., 20, 159–186, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0426(2003)020<0159:AUGFVT>2.0.CO;2, 2003. a

Constantinescu, A. M., Tyler, A. N., Stanica, A., Spyrakos, E., Hunter, P. D., Catianis, I., and Panin, N.: A century of human interventions on sediment flux variations in the Danube-Black Sea transition zone, Front. Mar. Sci., 10, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2023.1068065, 2023. a, b, c

Cucco, A., Umgiesser, G., Ferrarin, C., Perilli, A., Melaku Canu, D., and Solidoro, C.: Eulerian and lagrangian transport time scales of a tidal active coastal basin, Ecol. Model., 220, 913–922, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2009.01.008, 2009. a

Deltares: Delft3D Flexible Mesh Suite, Deltares, Tech. rep., Deltares, https://www.deltares.nl/en/software-and-data/products/delft3d-flexible-mesh-suite (last access: 25 October 2025), 2023. a

Dan, S., Stive, M., Walstra, D.-J. R., and Panin, N.: Wave climate, coastal sediment budget and shoreline changes for the Danube Delta, Mar. Geol., 262, 39–49, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2009.03.003, 2009. a

De Pascalis, F., Urbinati, E., Aalifar, A., Alcazar, L. A., Arpaia, L., Bajo, M., Barbanti, A., Barbariol, F., Bastianini, M., Bellafiore, D., Bellati, F., Benetazzo, A., Bologna, G., Bonaldo, D., Bongiorni, L., Braga, F., Brando, V. E., Brunetti, F., Caccavale, M., Camatti, E., Campostrini, P., Cantoni, C., Canu, D., Capotondi, L., Cassin, D., Castelli, G., Celussi, M., Correggiari, A., Cozzi, S., Dabalà, C., Davison, S., Fadini, A., Falcieri, F. M., Falcini, F., Ferrarin, C., Foglini, F., Gissi, E., Ghezzo, M., Grande, V., Guarneri, I., Lanzoni, A., Laurent, C., Lorenzetti, G., Madricardo, F., Manfè, G., Mc Kiver, W., Menegon, S., Moschino, V., Nesto, N., Petrizzo, A., Pomaro, A., Ravaioli, M., Remia, A., Riminucci, F., Rosina, A., Rosati, G., Santoleri, R., Scarpa, G., Scroccaro, I., Stanghellini, G., Solidoro, C., and Umgiesser, G.: The DANUBIUS-RI Supersite of Po Delta and North Adriatic Lagoons: a living lab on transitional environments in the Adriatic Sea, Estuarine Coastal Shelf Sci., 324, 109453, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2025.109453, 2025. a

Dinu, I., Umgiesser, G., Bajo, M., De Pascalis, F., Stanica, A., Pop, C., Dimitriu, R., Nichersu, I., and Constantinescu, A.: Modelling of the response of the Razelm Sinoie lagoon system to physical forcing, GeoEcoMarina, Zenodo, 21, 5–18, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.45064, 2015. a

EMODnet Bathymetry Consortium: EMODnet Digital Bathymetry (DTM 2022), EMODnet Bathymetry Consortium [data set], https://doi.org/10.12770/ff3aff8a-cff1-44a3-a2c8-1910bf109f85, 2022. a, b

Feizabadi, S., Li, C., and Hiatt, M.: Response of river delta hydrological connectivity to changes in river discharge and atmospheric frontal passage, Front. Mar. Sci., 11, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2024.1387180, 2024. a, b

Ferrarin, C., Ghezzo, M., Umgiesser, G., Tagliapietra, D., Camatti, E., Zaggia, L., and Sarretta, A.: Assessing hydrological effects of human interventions on coastal systems: numerical applications to the Venice Lagoon, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 17, 1733–1748, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-17-1733-2013, 2013. a, b

Ferrarin, C., Bajo, M., Bellafiore, D., Cucco, A., De Pascalis, F., Ghezzo, M., and Umgiesser, G.: Toward homogenization of Mediterranean lagoons and their loss of hydrodiversity, Geophys. Res. Lett., 41, 5935–5941, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014GL060843, 2014. a

Ferrarin, C., Bellafiore, D., Sannino, G., Bajo, M., and Umgiesser, G.: Tidal dynamics in the inter-connected Mediterranean, Marmara, Black and Azov seas, Prog. Oceanogr., 161, 102–115, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pocean.2018.02.006, 2018. a

Ferrarin, C., Davolio, S., Bellafiore, D., Ghezzo, M., Maicu, F., Drofa, O., Umgiesser, G., Bajo, M., De Pascalis, F., Malguzzi, P., Zaggia, L., Lorenzetti, G., Manfè, G., and Mc Kiver, W.: Cross-scale operational oceanography in the Adriatic Sea, J. Oper. Oceanogr., 12, 86–103, https://doi.org/10.1080/1755876X.2019.1576275, 2019. a

Ferrarin, C., Penna, P., Penna, A., Špada, V., Ricci, F., Bilić, J., Krzelj, M., Ordulj, M., Sikoronja, M., Duračić, I., Iagnemma, L., Bućan, M., Baldrighi, E., Grilli, F., Moro, F., Casabianca, S., Bolognini, L., and Marini, M.: Modelling the quality of bathing waters in the Adriatic Sea, Water, 13, 1525, https://doi.org/10.3390/w13111525, 2021. a

Fong, D. A. and Geyer, W. R.: Response of a river plume during an upwelling favorable wind event, J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans, 106, 1067–1084, https://doi.org/10.1029/2000JC900134, 2001. a

Fong, D. A. and Geyer, W. R.: The alongshore transport of freshwater in a surface-trapped river plume, J. Phys. Oceanogr., 32, 957–972, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0485(2002)032<0957:TATOFI>2.0.CO;2, 2002. a

Frank, G., Funk, A., Becker, I., Schneider, E., and Egger, G.: Chapter 16 – The key role of floodplains in nature conservation: How to improve the current status of biodiversity?, in: The Danube River and The Western Black Sea Coast, edited by Bloesch, J., Cyffka, B., Hein, T., Sandu, C., and Sommerwerk, N., Ecohydrology from Catchment to Coast, 335–364, Elsevier, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-443-18686-8.00008-1, 2025. a

Garvine, R. W.: A dynamical system for classifying buoyant coastal discharges, Cont. Shelf Res., 15, 1585–1596, https://doi.org/10.1016/0278-4343(94)00065-U, 1995. a

Geuzaine, C. and Remacle, J.-F.: Gmsh: A 3-D finite element mesh generator with built-in pre- and post-processing facilities, Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng., 79, 1309–1331, https://doi.org/10.1002/nme.2579, 2009. a

Giosan, L., Donnelly, J. P., Constantinescu, S., Filip, F., Ovejanu, I., Vespremeanu-Stroe, A., Vespremeanu, E., and Duller, G. A.: Young Danube delta documents stable Black Sea level since the middle Holocene: Morphodynamic, paleogeographic, and archaeological implications, Geology, 34, 757–760, https://doi.org/10.1130/G22587.1, 2006. a

Hariharan, J., Wright, K., Moodie, A., Tull, N., and Passalacqua, P.: Impacts of human modifications on material transport in deltas, Earth Surf. Dynam., 11, 405–427, https://doi.org/10.5194/esurf-11-405-2023, 2023. a

Hersbach, H., Bell, B., Berrisford, P., Hirahara, S., Horànyi, A., Munoz-Sabater, J., Nicolas, J., Peubey, C., Radu, R., Schepers, D., Simmons, A., Soci, C., Abdalla, S., Abellan, X., Balsamo, G., Bechtold, P., Biavati, G., Bidlot, J., Bonavita, M., De Chiara, G., Dahlgren, P., Dee, D., Diamantakis, M., Dragani, R., Flemming, J., Forbes, R., Fuentes, M., Geer, A., Haimberger, L., Healy, S., Hogan, R. J., Hólm, E., Janisková, M., Keeley, S., Laloyaux, P., Lopez, P., Lupu, C., Radnoti, G., de Rosnay, P., Rozum, I., Vamborg, F., Villaume, S., and Thépaut, J.-N.: The ERA5 global reanalysis, Q. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 146, 1999–2049, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.3803, 2020. a

Horner-Devine, A. R., Hetland, R. D., and MacDonald, D. G.: Mixing and Transport in Coastal River Plumes, Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech., 47, 569–594, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-fluid-010313-141408, 2015. a, b

Kjerfve, B.: Comparative oceanography of coastal lagoons, in: Estuarine Variability, edited by D. A. Wolfe, 63–81, Academic Press, New York, USA, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-761890-6.50009-5, 1986. a

Kolb, P., Zorndt, A., Burchard, H., Gräwe, U., and Kösters, F.: Modelling the impact of anthropogenic measures on saltwater intrusion in the Weser estuary, Ocean Sci., 18, 1725–1739, https://doi.org/10.5194/os-18-1725-2022, 2022. a

Li, M., Najjar, R. G., Kaushal, S., Mejia, A., Chant, R. J., Ralston, D. K., Burchard, H., Hadjimichael, A., Lassiter, A., and Wang, X.: The emerging global threat of salt contamination of water supplies in tidal rivers, Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett., 12, 881–892, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.estlett.5c00505, 2025. a

Lima, L., Aydogdu, A., Escudier, R., Masina, S., Ciliberti, S. A., Azevedo, D., Peneva, E. L., Causio, S., Cipollone, A., Clementi, E., Cretí, S., Stefanizzi, L., Lecci, R., Palermo, F., Coppini, G., Pinardi, N., and Palazov, A.: Black Sea Physical Reanalysis (CMEMS BLK-Physics, E3R1 system) (Version 1), Copernicus Monitoring Environment Marine Service (CMEMS) [data set], https://doi.org/10.25423/CMCC/BLKSEA_MULTIYEAR_PHY_ 007_004, 2020. a, b, c

Maicu, F., De Pascalis, F., Ferrarin, C., and Umgiesser, G.: Hydrodynamics of the Po River-Delta-Sea system, J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans, 123, 6349–6372, https://doi.org/10.1029/2017JC013601, 2018. a, b, c

Maselli, V. and Trincardi, F.: Man made deltas, Sci. Rep., 3, 1926, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01926, 2013. a

Miladinova, S., Stips, A., Macias Moy, D., and Garcia-Gorriz, E.: Pathways and mixing of the north western river waters in the Black Sea, Estuarine Coastal Shelf Sci., 236, 106630, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2020.106630, 2020. a, b

Newton, A., Mistri, M., Pérez-Ruzafa, A., and Reizopoulou, S.: Editorial: Ecosystem services, biodiversity, and water quality in transitional ecosystems, Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 11, https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2023.1136750, 2023. a

Nichersu, I., Livanov, O., Mierlǎ, M., Trifanov, C., Simionov, M., Lupu, G., Ibram, O., Burada, A., Despina, C., Covaliov, S., Doroftei, M., Doroşencu, A., Bolboacǎ, L., Nǎstase, A., Ene, L., and Balaican, D.: Chapter 6 – The Danube Delta – The link between the Danube River and the Black Sea, in: The Danube River and The Western Black Sea Coast, edited by Bloesch, J., Cyffka, B., Hein, T., Sandu, C., and Sommerwerk, N., Ecohydrology from Catchment to Coast, 107–122, Elsevier, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-443-18686-8.00002-0, 2025. a, b

Panin, N.: Impact of global changes on geo-environmental and coastal zone state of the Black Sea, GeoEcoMarina, 1, 7–23, 1996. a

Panin, N.: Danube Delta: Geology, Sedimentology, Evolution, Association des Sédimentologistes Français, 1998. a, b

Panin, N.: Global changes, sea level rise and the Danube Delta: risks and responses, GeoEcoMarina, 4, 19–29, 1999. a

Passalacqua, P.: The Delta Connectome: A network-based framework for studying connectivity in river deltas, Geomorphology, 277, 50–62, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2016.04.001, 2017. a

Payo-Payo, M., Bricheno, L. M., Dijkstra, Y. M., Cheng, W., Gong, W., and Amoudry, L. O.: Multiscale temporal response of salt intrusion to transient river and ocean forcing, J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans, 127, e2021JC017523, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021JC017523, 2022. a

Pein, J., Staneva, J., Mayer, B., Palmer, M., and Schrum, C.: A framework for estuarine future sea-level scenarios: Response of the industrialised Elbe estuary to projected mean sea level rise and internal variability, Frontiers in Marine Science, 10, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2023.1102485, 2023. a

Pekárová, P., Mèszáros, J., Miklánek, P., Pekár, J., Prohaska, S., and Ilić, A.: Long-term runoff variability analysis of rivers in the Danube basin, Acta Horticulturae et Regiotecturae, 24, 37–44, https://doi.org/10.2478/ahr-2021-0008, 2021. a

Pérez-Ruzafa, A., Pérez-Ruzafa, I. M., Newton, A., and Marcos, C.: Chapter 15 – Coastal Lagoons: Environmental Variability, Ecosystem Complexity, and Goods and Services Uniformity, in: Coasts and Estuaries, edited by Wolanski, E., Day, J. W., Elliott, M., and Ramachandran, R., 253–276, Elsevier, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-814003-1.00015-0, 2019. a

Probst, E. and Mauser, W.: Climate Change Impacts on Water Resources in the Danube River Basin: A Hydrological Modelling Study Using EURO-CORDEX Climate Scenarios, Water, 15, https://doi.org/10.3390/w15010008, 2023. a

Schimanke, S., Ridal, M., Le Moigne, P., Berggren, L., Undén, P., Randriamampianina, R., Andrea, U., Bazile, E., Bertelsen, A., Brousseau, P., Dahlgren, P., Edvinsson, L., El Said, A., Glinton, M., Hopsch, S., Isaksson, L., Mladek, R., Olsson, E., Verrelle, A., and Wang, Z. Q.: CERRA sub-daily regional reanalysis data for Europe on single levels from 1984 to present, Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS) [data set], https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.622a565a, 2021. a, b

Shen, Y., Jia, H., Li, C., and Tang, J.: Numerical simulation of saltwater intrusion and storm surge effects of reclamation in Pearl River Estuary, China, Applied Ocean Research, 79, 101–112, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apor.2018.07.013, 2018. a

Simpson, J. H., Bos, W., Schirmer, F., Souza, A., Rippeth, T., Jones, S., and Hydes, D.: Periodic stratification in the Rhine ROFI in the North Sea, Oceanologica Acta, 16, 23–32, 1993. a