the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Temperature effect on seawater fCO2 revisited: theoretical basis, uncertainty analysis and implications for parameterising carbonic acid equilibrium constants

Matthew P. Humphreys

The sensitivity of the fugacity of carbon dioxide in seawater (fCO2) to temperature (denoted υ, reported in % °C−1) is critical for the accurate fCO2 measurements needed to build global carbon budgets and for understanding the drivers of air–sea CO2 flux variability across the ocean. However, understanding and computing υ have been restricted to either using empirical functions fitted to experimental data or determining it as an emergent property of a fully resolved marine carbonate system, and these two approaches are not consistent with each other. The lack of a theoretical basis and an uncertainty estimate for υ has hindered resolving this discrepancy. Here, we develop a new approach for calculating the temperature sensitivity of fCO2 based on the equations governing the marine carbonate system and the van 't Hoff equation. This shows that, to first order, ln (fCO2) should be proportional to (where tK is temperature in kelvin), rather than to temperature, as has previously been assumed. This new approach is, to first order, consistent with calculations from a fully resolved marine carbonate system, which we have incorporated into the PyCO2SYS software. Agreement with experimental data is less convincing but remains inconclusive due to the scarcity of direct measurements of υ, particularly above 25 °C. However, the new approach is consistent with field data, performing better than any other approach for adjusting fCO2 by up to 10 °C if spatiotemporal variability in its single fitted coefficient is accounted for. The uncertainty in υ arising from only measurement uncertainty in the main experimental dataset where υ has been directly measured is in the order of 0.04 % °C−1, which corresponds to a 0.04 % uncertainty in fCO2 adjusted by +1 °C. However, spatiotemporal variability in υ is several times greater than this, so the true uncertainty due to the temperature adjustment in fCO2 adjusted by +1 °C using the most widely used constant υ value is around 0.24 %. This can be reduced to around 0.06 % using the new approach proposed here, and this could be further reduced by more measurements. The spatiotemporal variability in υ arises mostly from the equilibrium constants for CO2 solubility and carbonic acid dissociation ( and ), and its magnitude varies significantly depending on which parameterisation is used for and . Seawater fCO2 can be measured accurately enough that additional experiments should be able to detect spatiotemporal variability in υ and distinguish between different parameterisations for and . Because the most widely used constant υ was coincidentally measured from seawater with roughly global average υ, our results are unlikely to significantly affect global air–sea CO2 flux budgets, but they may have more important implications for regional budgets and studies that adjust by larger temperature differences.

- Article

(5468 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(1408 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

The surface ocean continuously exchanges carbon dioxide (CO2) with the atmosphere. The net direction of exchange varies through space and time, with some ocean areas acting as CO2 sources and others as sinks (Takahashi et al., 2009). Whether an area acts as a CO2 source or sink depends on the difference between the fugacity of CO2 (fCO2) in the sea and in the air (denoted ), with net CO2 transfer from high to low fCO2. The fugacity of CO2 is similar to its partial pressure (pCO2) but with a small correction for the non-ideal behaviour of CO2 in air; fCO2 is typically about 99.7 % of pCO2. The gas exchange rate is modulated by a set of processes that are commonly parameterised as a function of wind speed (Wanninkhof, 2014). Most of the surface ocean is either a CO2 source or sink, rather than being in equilibrium with the atmosphere, because many of the processes that modify seawater fCO2 (e.g. seasonal cycles of temperature and primary productivity) operate on faster timescales than air–sea CO2 equilibration, which takes from months to a year for the surface mixed layer (Jones et al., 2014).

On top of the natural background variability, the global ocean is a net CO2 sink due to rising atmospheric fCO2. About a quarter of the anthropogenic CO2 emitted each year, some 2.8 ± 0.4 Gt C in 2022, is taken up by the ocean, mitigating the greenhouse effect of CO2 on Earth's climate (Friedlingstein et al., 2023). Together, uptake of CO2 and warming drive changes in the marine carbonate system, altering biologically important variables like seawater pH and the saturation states with respect to carbonate minerals (Humphreys, 2017). Quantifying marine CO2 uptake requires highly accurate fCO2 measurements: it is driven by a global mean ΔfCO2 of −4.1 ± 1.6 µatm (Fay et al., 2024), which is around 2 % of mean fCO2. Consequently, small systematic biases in seawater fCO2 propagate into large errors in ΔfCO2 and, thus, the total ocean CO2 sink. The required measurement accuracy has been quantified by the Global Ocean Acidification Observing Network (GOA-ON), with the network suggesting a minimum accuracy of 0.5 % (i.e. around 2 µatm) for “climate quality” seawater fCO2 measurements that can be used to detect decadal trends or 2.5 % (∼10 µatm) for “weather quality” fCO2 data to investigate changes of greater magnitude, such as seasonal cycles (Newton et al., 2015).

The observational constraint on marine CO2 uptake is based on measurements of surface ocean fCO2 from ships, compiled into data products such as the Surface Ocean CO2 Atlas (SOCAT; Bakker et al., 2016). Surface seawater is equilibrated with an enclosed headspace, which flows through to a measuring device, and the raw measurements are passed through a series of processing steps to obtain seawater fCO2. One important processing step is the temperature adjustment. While it is being pumped from the surface ocean to the equilibration chamber, seawater may warm up or cool down. As fCO2 is highly sensitive to temperature (Weiss, 1974), each measurement must be adjusted back to its in situ temperature in order to obtain environmentally relevant values of fCO2 (Pierrot et al., 2009; Pfeil et al., 2013; Goddijn-Murphy et al., 2015). For the data in SOCAT with the most stringent quality control flags (A and B), a maximum change in temperature (Δt) of 1 °C between intake and measurement is permitted (although adjustments are usually around 0.2–0.3 °C in practice; Wanninkhof et al., 2022a), in order to minimise uncertainty in fCO2 due to the temperature adjustment. Adjustments with greater Δt are often used in other applications. Some groups measure fCO2 in discrete samples at a constant temperature, which must then be adjusted by up to 20 °C to return to in situ conditions (Wanninkhof et al., 2022a). Several studies have normalised seawater fCO2 observations to a constant temperature in order to investigate the non-thermal (i.e. chemical) drivers of fCO2 change on various timescales (e.g. Takahashi et al., 2002, 2003, 2006; Feely et al., 2006). Others have computed the temperature sensitivity in order to isolate the thermal component of observed fCO2 change and unravel the drivers of fCO2 variability (e.g. Metzl et al., 2010; Fassbender et al., 2022; Rodgers et al., 2023). Data from SOCAT have been adjusted from the intake temperature, typically measured a few metres below the sea surface, to the temperature directly at the sea surface in order to assess how the “cool skin” effect affects computed air–sea CO2 fluxes (e.g. Watson et al., 2020; Dong et al., 2022). Finally, climatological fCO2 datasets have been adjusted to match different sea surface temperature fields for specific analyses (e.g. Kettle et al., 2009; Land et al., 2013), and this functionality is part of published data processing toolkits (e.g. Shutler et al., 2016; Holding et al., 2019).

The most widely used approach to adjust fCO2 data to different temperatures (t), used in all of the examples above, is based on data from Takahashi et al. (1993), who measured the variation in fCO2 with temperature in one seawater sample from the North Atlantic Ocean (strictly speaking, they reported pCO2, but the results apply equally to fCO2). Their measurements indicated that the temperature sensitivity of fCO2 (denoted υ; Eq. 1) was essentially independent of fCO2 and temperature (i.e. temperature and ln (fCO2) have a linear relationship). This apparent near-linearity was consistent with earlier measurements by Kanwisher (1960) on a single seawater sample collected from the vicinity of Woods Hole (Massachusetts, USA) and with later measurements by Lee and Millero (1995). Takahashi et al. (1993) also claimed that the value of υ was no different for higher-salinity waters, citing unpublished preliminary data.

However, it has long been known that υ is not constant across the ocean. For example, Gordon and Jones (1973) computed υ using a finite-difference approach across a range of different temperature, salinity, alkalinity and pH values and found that the variability in υ could be approximately parameterised as a function of pCO2. Using a similar approach but with different parameterisations of the equilibrium constants in their marine carbonate system calculations, Weiss et al. (1982) and Copin-Montegut (1988) each fitted υ to functions of fCO2 and temperature. It has been noted that υ may vary with the dissolved inorganic carbon (TC) content of seawater (e.g. Takahashi et al., 2002) or, more generally, with the ratio between TC and total alkalinity (AT) (e.g. Goyet et al., 1993; Wanninkhof et al., 2022a).

There are also several lines of evidence that the relationship between temperature and ln (fCO2) is not linear (i.e. υ is not constant for a single, isochemical sample). Takahashi et al. (1993) acknowledged this possibility by fitting ln (fCO2) to a quadratic function of temperature as well as their linear function, although they did not give any reason to choose one over the other. The fits of Weiss et al. (1982), Copin-Montegut (1988) and Goyet et al. (1993) included various degrees of polynomial temperature dependence. Calculating how fCO2 changes with temperature using software tools like CO2SYS (Lewis and Wallace, 1998) also shows a non-linear relationship, but its exact form and how much it deviates from linearity both vary widely depending on which parameterisation for the equilibrium constants of carbonic acid is used (McGillis and Wanninkhof, 2006). Data compiled from multiple cruises during which fCO2 was measured at two different temperatures in an equivalent pair of samples, often with accompanying AT and TC, showed that a linear (constant υ) adjustment was insufficiently accurate for Δt greater in magnitude than about 1 °C (Wanninkhof et al., 2022a).

Wanninkhof et al. (2022a) recommended calculating υ from AT and TC in order to make accurate adjustments with greater Δt, using the carbonic acid dissociation constants of Lueker et al. (2000) and the borate-to-chlorinity ratio of Uppström (1974). However, the requirement for a second marine carbonate system parameter (other than fCO2) is a major disadvantage because, due to ships of opportunity and the variety of (semi-)autonomous sensors available, seawater fCO2 is by far the most widely measured marine carbonate system parameter in the ocean and is often the only one available at a particular observation point. A possible workaround would be to use a parameterisation to generate values for a second parameter. For example, across much of the open ocean, AT can be calculated from temperature and salinity with an uncertainty of less than 10 µmol kg−1 (Lee et al., 2006). Under typical conditions, this component alone would propagate through to a less than 0.1 µatm uncertainty in fCO2 adjusted by 10 °C (calculated with PyCO2SYS; Humphreys et al., 2022). However, this ignores the much larger contribution of uncertainties in the equilibrium constants used in the calculations. These are not well constrained, but using the set suggested by Orr et al. (2018) makes the uncertainty in the same adjusted fCO2 value several hundred times greater, at around 15 µatm. An adjustment method based on direct measurements of fCO2 and independent from a second marine carbonate system parameter, avoiding the uncertainties inherent in calculations involving equilibrium constants, is therefore highly desirable.

Given the evidence that the equations of Takahashi et al. (1993) are not sufficiently accurate for the full range of temperature adjustments of fCO2 required by ocean scientists, why do they remain so widely used? First, they are straightforward to calculate, relying only on variables that will be available with any fCO2 measurement (i.e. fCO2 itself and temperature). The more complex existing parameterisations that also fulfil this criterion (Copin-Montegut, 1988; e.g. Gordon and Jones, 1973; Weiss et al., 1982) are not based on up-to-date parameterisations of the carbonic acid dissociation constants, which can lead to differences in adjusted fCO2 values of over 30 µatm for larger Δt (McGillis and Wanninkhof, 2006). However, a more fundamental impediment is not knowing what form the relationship between temperature and ln (fCO2) should be expected to take from a theoretical perspective. Should it be (roughly) linear, with deviations from linearity thus indicating problems with the calculations used to solve the marine carbonate system, or should it be non-linear, thus indicating some deficiency with the measurements of Takahashi et al. (1993)? With respect to the latter, this then poses the follow-up question of which of the non-linear relationships obtained from the different parameterisations of the carbonic acid dissociation constants should be followed.

Here, we aim to provide this missing theoretical basis by developing a new functional form regarding how fCO2 and, thus, υ vary with temperature, derived from the equations governing the marine carbonate system and the van 't Hoff equation. We compare this new form with υ calculated from a fully resolved marine carbonate system – to which end, we have added the calculation of υ to PyCO2SYS (Humphreys et al., 2022) – and with laboratory and field data. We compute uncertainties in υ and temperature-adjusted fCO2 values due to experimental uncertainties and variability in υ through space and time. We assess the contributions of the different equilibrium constants of the marine carbonate system to υ, especially those for carbonic acid dissociation, and consider the implications for how these constants are parameterised and how these previously separate aspects can be better integrated in future studies for a more accurate and internally consistent understanding of the marine carbonate system.

2.1 Adjusting fCO2 to a different temperature

2.1.1 General theory

The temperature sensitivity of seawater fCO2 (υ, in units of % °C−1) is the first derivative of the natural logarithm of fCO2 with respect to temperature (t, in °C) under constant total alkalinity (AT) and dissolved inorganic carbon (TC) (see Humphreys et al., 2022, and references therein for more detailed definitions of AT, TC and fCO2):

We note that, here and throughout, fCO2 must be divided by the unit of fCO2 (e.g. 1 µatm if fCO2 is in µatm) before taking the logarithm, and “constant AT and TC” implies that all other parameters but temperature are also constant (e.g. salinity and total nutrient contents). We report υ in percent per degree Celsius (% °C−1; i.e. 10−2 °C−1).

To adjust an fCO2 value from one temperature (t0) to another (t1), υ must be integrated across the relevant temperature range:

where Υ denotes the integral

Equivalent to Eq. (2),

Thus, in order to adjust the temperature of an fCO2 value using Eq. (4), a function for υ that can be integrated with respect to temperature is needed.

2.1.2 Experiments to measure υ

Takahashi et al. (1993) attempted to determine υ by measuring how pCO2 varies with temperature (eight measurements at seven temperatures from 2.1 to 24.5 °C) in one seawater sample with constant AT (reported as “2270 to 2295” µmol kg−1) and TC (2074 µmol kg−1). The practical salinity was 35.380. Phosphate and silicate concentrations were reported as zero while noting the possibility of silicate contamination from the sample bottles. The sample had been part of the laboratory intercomparison exercise reported by Poisson et al. (1990).

We determined a more precise AT for the sample by finding the value that, when paired with the TC and other parameters above, returned the least-squares best fit to the reported pCO2 values. When using the Lueker et al. (2000) carbonic acid constants and the borate-to-chlorinity ratio of Uppström (1974), the AT obtained with PyCO2SYS (Humphreys et al., 2022) was 2263 ± 3 µmol kg−1, although each set of carbonic acid constants returned its own unique AT. For consistency with modern measurements and the rest of our analysis, we also converted the Takahashi et al. (1993) pCO2 values into fCO2, although this makes no meaningful difference to any of our results.

Takahashi et al. (1993) fitted their pCO2 dataset to linear (subscript l) and quadratic (subscript q) equations (here written in terms of fCO2):

where a, b and c are the fitted coefficients. Differentiating with respect to t yields the following for υ:

Finally, integrating across the relevant temperature range yields Υ, following, for example, Takahashi et al. (2009):

Takahashi et al. (1993) reported values of bl=4.23 % °C−1, °C−2 and bq=4.33 % °C−1 with a root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of 1.0 µatm in fCO2 for both fits. Reproducing these fits with their reported data gives an RMSD of 1.2 µatm for the linear fit and 0.9 µatm for the quadratic.

Lee and Millero (1995) conducted a similar set of measurements as part of a wider experimental study of the marine carbonate system. Again using only one single sample, they measured the variation in fCO2 with temperature at roughly 5 °C intervals from 5.05 to 35 °C (seven data points). The reproducibility of the fCO2 measurements was reported as ±3 µatm. The properties of the sample were reported as AT=2320.8 ± 1.6 µmol kg−1, TC=1966.8 ± 1.2 µmol kg−1 and salinity=34.95. The experimental set-up was a little different; for example, Takahashi et al. (1993) equilibrated the sample with an air headspace that was subsampled for separate measurement, whereas Lee and Millero (1995) continuously circulated the air headspace through the CO2 analyser. Lee and Millero (1995) fitted a linear equation of the form of Eq. (5) to their data, finding a best-fitting υl of 4.26 % °C−1. Refitting their dataset but minimising residuals in fCO2 rather than ln (fCO2) returns % °C−1.

2.1.3 The van 't Hoff equation approach

Takahashi et al. (1993) did not give a theoretical basis for either of the forms (linear and quadratic; Eqs. 5 and 6) that they fitted to their dataset, nor did they give any reason to choose one over the other. However, as will be discussed later, the form chosen has an important effect on adjustments, especially over greater Δt (Sect. 3.1), and on uncertainty propagation (Sect. 3.2). Here, we provide the theoretical basis for an alternative form based on the equations governing the marine carbonate system and the van 't Hoff equation, which is derived from the well-known thermodynamic equation for the Gibbs free energy of chemical reactions.

Seawater fCO2 is related to AT and TC by (e.g. Humphreys et al., 2018)

The asterisks in and show that they are stoichiometric equilibrium constants, based on the substance contents of the equilibrating species, rather than thermodynamic constants based on their activities; the prime symbol in shows that it is a hybrid equilibrium constant, based on the substance content of CO2(aq) and the fugacity of CO2(g) (Zeebe and Wolf-Gladrow, 2001). Following Humphreys et al. (2018), AT and TC can be approximated with Ax and Tx, which include only the bicarbonate () and carbonate () terms:

In typical seawater, the approximations in Eqs. (12) and (13) are more than 99 % accurate for TC and more than 97 % accurate for AT. These approximations have previously been used to understand how fCO2 responds to changes in AT and TC under constant temperature (Humphreys et al., 2018). Equations (12) and (13) can be rearranged for [] and []:

Under this approximation, both [] and [] are constant under constant Ax and Tx, so temperature affects fCO2 only through the term in Eq. (11). To relate this to υ, we need to quantify this sensitivity to temperature:

The van 't Hoff equation provides a theoretical basis for the first-order response of equilibrium constants to temperature:

where ΔrH⊖ is the standard enthalpy of the reaction, R is the ideal gas constant and tK is the temperature in kelvin. Substituting Eq. (17) into Eq. (16) gives

Equation (18) shows that, if the approximations Ax and Tx are sufficiently accurate, then (to first order) ln (fCO2) should be proportional to , rather than to t.

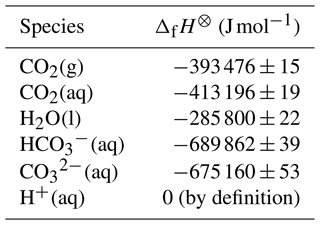

Based on reported standard enthalpies of formation at 298.15 K (Ruscic and Bross, 2023), and assuming that these are constant under the temperature range of interest, the numerator in Eq. (18) is 25 288 ± 98 J mol−1 (Appendix A). Given the approximations involved, Eq. (18) is unlikely to provide correct values for υ in seawater directly by using this value, but it does suggest a revised form that could be fitted to experimental data such as those of Takahashi et al. (1993):

Following the same steps taken in Sect. 2.1.2 for the linear and quadratic forms of Takahashi et al. (1993), we find the following:

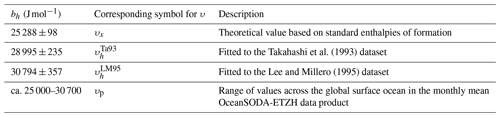

We fitted Eq. (19) to the Takahashi et al. (1993) dataset, optimising residuals in fCO2 rather than ln (fCO2) to avoid implicitly weighting the lower-fCO2 values more heavily. The least-squares best-fit bh was 28 995 ± 235 J mol−1, with an RMSD of 2.9 µatm in fCO2. Fitting Eq. (19) in the same way to the Lee and Millero (1995) dataset gave a least-squares best-fit bh of 30 794 ± 357 J mol−1, with an RMSD of 2.8 µatm. The different bh values considered here are summarised in Table 1, including the parameterisation developed later in Sect. 2.4, which gives a range of possible values.

2.2 Uncertainty in the experiment

2.2.1 Propagation equations

To quantify uncertainties in fCO2 resulting from temperature adjustments, one needs to know the uncertainty in υ and Υ for whichever form is being used. Here, we derive uncertainty propagation equations following JCGM (2008) for the linear (Eq. 5), quadratic (Eq. 6) and van 't Hoff (Eq. 19) forms.

For the linear and van 't Hoff forms, uncertainty propagation is straightforward:

where σ2 is uncertainty expressed as a variance.

For the quadratic form, covariances between the fitted coefficients must be included. In general,

where p is the parameter of interest and the uncertainty matrix for the coefficients is

The Jacobian matrices for υq and Υq are

Thus, for a single measurement, Eq. (26) gives

Finally, uncertainty in Υ can be converted into uncertainty in exp (Υ) for use in Eq. (4) with

2.2.2 Uncertainties in fitted parameters

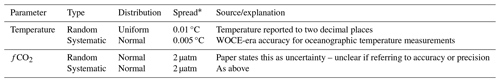

To use the equations in Sect. 2.2.1, the uncertainties in the fitted parameters from Eqs. (5), (6) and (19) must be known. We computed these by running Monte Carlo simulations of the Takahashi et al. (1993) experiment, as this dataset is the most widely used in practice.

We used the Takahashi et al. (1993) temperature and fCO2 measurements as the starting point for the simulations. For each iteration of the simulation (total iterations = 106), we generated a random number for each of temperature and fCO2, which were added uniformly across the entire dataset to represent systematic errors (trueness), and then a different random number for each temperature and fCO2 data point, to represent random errors in each measurement (precision). The distributions used for the random numbers are shown in Table 2. The simulated temperature and fCO2 values (starting point plus systematic and random errors) were then fitted to Eqs. (5), (6) and (19) separately in each iteration. All of the forms of υ and Υ were also computed based on the fit at each iteration.

Table 2Uncertainties in temperature and seawater fCO2 assumed for our Monte Carlo simulations of the Takahashi et al. (1993) experiment.

∗ Spread indicates the total range for uniform distributions or the standard deviation for normal distributions, with both distributions centred at zero.

The variances σ2(bl) and σ2(bh) and the variance–covariance matrix Uq (Eq. 27) were computed from the fitted coefficients across the full set of iterations.

2.2.3 Validation of uncertainty propagation

The uncertainty propagation equations in Sect. 2.2.1 have all been validated by two comparisons: (1) with the variances of the υ and Υ values computed across all of the simulations in Sect. 2.2.2 and (2) by computing the derivatives required for propagation using automatic differentiation (Maclaurin, 2016) rather than manually. The values from the equations agreed to within 0.01 % with those based on the simulations and to within 10−12 % with the calculations based on automatic differentiation. The former difference is greater (albeit still negligible) because of non-linearities in the forms of υ that are not accounted for in the first-order derivatives used for uncertainty propagation here. The latter difference is attributable to rounding errors at the limit of computer precision.

2.3 PyCO2SYS extension and calculations

PyCO2SYS is a free, open-source Python package that can be used to solve the marine carbonate system, i.e. to calculate the equilibrium balance of the main acid–base systems in seawater and related properties (Humphreys et al., 2022). PyCO2SYS was originally based on the MATLAB/GNU Octave program CO2SYS.m (v2.0.5; Orr et al., 2018) – itself part of a family of similar software tools beginning with the original CO2SYS for MS-DOS (Lewis and Wallace, 1998).

2.3.1 Calculating υ in PyCO2SYS

In PyCO2SYS, υ can be calculated by finite differences or by automatic differentiation (Maclaurin, 2016). The accuracy of the former depends on the size of the difference used, whereas the latter gives the exact result directly (Humphreys et al., 2022). For consistency with the chemical buffer factors in PyCO2SYS, we used automatic differentiation to calculate υ. We constructed a function that evaluates ln (fCO2) from AT, TC, t and all other relevant parameters (e.g. salinity, pressure and nutrients) and applied automatic differentiation to determine its derivative with respect to temperature. The function runs after AT and TC have been determined from whichever pair of known parameters the user provides. This was added to the set of results returned by PyCO2SYS as of v1.8.3 (Humphreys et al., 2024).

Previous versions of PyCO2SYS could already calculate using forward finite-difference derivatives as part of the uncertainty propagation tool. υ can be calculated from as follows:

We used the finite-difference and Eq. (33) to validate the values from automatic differentiation. Across 104 random combinations of AT, TC, salinity, t, pressure, nutrient contents and carbonic acid dissociation constant parameterisation, we found that the two approaches were consistent, with a mean absolute difference of less than 10−4 % °C−1 (or 0.01 %) and a maximum absolute difference of less than 0.1 % °C−1. This check has been incorporated into the PyCO2SYS test suite to ensure continued consistency in future versions.

2.3.2 Adjusting fCO2 to different temperatures

Prior to v1.8.3, PyCO2SYS could already convert fCO2 (also pCO2, [CO2(aq)] or xCO2) values from one temperature to another when no second carbonate system variable was provided, although using only Eq. (10), the quadratic fit of Takahashi et al. (1993). In v1.8.3, we have added the option to use the other methods discussed here instead, i.e. the linear fit of Takahashi et al. (1993) and the van 't Hoff form with several different options for bh, including its parameterisation in Sect. 2.4.

As in previous versions of PyCO2SYS, the same adjustment is applied if pCO2, [CO2(aq)] or xCO2 is given as the single known marine carbonate system parameter, as these can all be inter-converted with each other and with fCO2 without knowledge of a second marine carbonate system parameter (Humphreys et al., 2022).

2.3.3 Components of υ

The effect of temperature on fCO2 propagates through from all of the different equilibrium constants of the marine carbonate system. The total υ is the sum of the partial derivatives with respect to each constant:

where K is the set of equilibrium constants and other properties that are sensitive to t and involved in calculating fCO2 from AT and TC, specifically, the CO2 solubility constant , the carbonic acid dissociation constants and , the borate equilibrium constant , and the water dissociation constant . The dissociation constants for phosphoric acid, orthosilicic acid, hydrogen sulfide, ammonia, sulfate and hydrogen fluoride also play a role, but their contributions to υ are negligible, being much less than 1 % in the modern surface ocean, so we did not include them further in our analysis. (Their effects are still included in the total υ calculated with automatic differentiation, described in Sect. 2.3.1.)

We used the forward finite-difference derivatives calculated by PyCO2SYS (Humphreys et al., 2022) to evaluate and and combined these with Eq. (33) to quantify the influence of each component on υ.

2.3.4 Additional carbonic acid parameterisation

We incorporated the parameterisation of Papadimitriou et al. (2018) for the carbonic acid dissociation constants into PyCO2SYS. This parameterisation covers a range of temperature (−6 to 25 °C) and salinity (33 to 100) conditions appropriate for sea-ice brines; previously, the lowest valid temperature for any parameterisation in PyCO2SYS was −1.7 °C and the highest salinity was 50. The calculations were tested against the check values provided by Papadimitriou et al. (2018) in their Table 3, and these tests were incorporated into the PyCO2SYS automatic test suite (Humphreys et al., 2022).

2.4 Variability in υ and bh

We used the OceanSODA-ETZH data product (Gregor and Gruber, 2021; dataset version 5, downloaded 4 December 2023) to investigate spatiotemporal variability in surface ocean υ. OceanSODA-ETZH provides fields of several marine carbonate system and other hydrographic parameters gridded across the surface ocean (1°×1°) and through time (monthly from 1985 to 2018). The parameter fields were generated using an ensemble cluster–regression approach based on observations in SOCAT (Bakker et al., 2016) and GLODAP (Lauvset et al., 2016). Other similar data products exist, but the main patterns and variability in surface ocean carbonate chemistry are well enough constrained that the choice of a particular data product will not significantly affect the global-scale and time-averaged analyses conducted here.

First, at each grid point and for each month, we computed the mean across all years of temperature, salinity, AT and TC. We then computed υ from these monthly mean gridded fields using PyCO2SYS v1.8.3 (Sect. 2.3), with the carbonic acid dissociation constants of Lueker et al. (2000), the bisulfate dissociation constant of Dickson (1990a), the hydrogen fluoride dissociation constant of Dickson and Riley (1979), and the total borate-to-chlorinity ratio of Uppström (1974). OceanSODA-ETZH does not include nutrient fields, so their concentrations were set to zero, but we do not expect this to affect the results because, as noted in Sect. 2.3.2, their effects on υ are negligible.

We also used the OceanSODA-ETZH data product to parameterise bh. We calculated fCO2 at 50 evenly spaced temperatures from −1.8 to 35.83 °C (i.e. the full range in the data product) at each monthly mean grid point. This simulates running an experiment like that of Takahashi et al. (1993) at each point. Next, we fit Eq. (19) to the generated t and fCO2 data to find the best-fitting bh value at each point. Finally, we collated all of the bh values and fitted them using a function of the following form:

where s is practical salinity, f is fCO2 and u0–u9 are the fitted coefficients. The coefficients and their variance–covariance matrix are provided in the Supplement (Tables S1 and S2). Values of υ computed using Eq. (35) for bh are denoted υp.

Fitting the parameterisation to a data product has an advantage over using regular grids of the predictors in that it guarantees including all combinations of predictors that do occur in the real ocean and avoids combinations that do not. It also causes the fit to be weighted more strongly by more prevalent combinations of conditions, leading to improved performance in global applications. However, some regions are less well represented by this global fit (Fig. S1 in the Supplement), so regionally specialised fits might work better for some studies.

A difficulty with applying our parameterisation of bh is that in situ fCO2 is one of the predictors. This may not always be known (e.g. if discrete measurements were conducted at a fixed temperature in the laboratory), and using a different fCO2 will not yield an accurate bh. To mitigate this issue, if in situ fCO2 is not known before the conversion, we use the constant bh fitted to the Takahashi et al. (1993) dataset (Sect. 2.1.3) to preliminarily adjust fCO2 to the in situ temperature; we then use this preliminary fCO2 to compute bh with Eq. (35) before recalculating in situ fCO2 with the computed bh. This approach is incorporated into the PyCO2SYS implementation, with the user required to identify whether the input- or output-condition fCO2 values represent in situ conditions for this purpose.

2.5 Open-source software

All of the analysis presented here was conducted using the free and open-source Python programming language (Python Software Foundation; https://www.python.org/, last access: 23 October 2024). The main packages used, which are also free and open source, include NumPy (Harris et al., 2020), Autograd (Maclaurin, 2016) and Xarray (Hoyer and Hamman, 2017) for data manipulation and general calculations; SciPy (Virtanen et al., 2020) for curve fitting; Matplotlib (Hunter, 2007) and Cartopy (Met Office, 2010) for data visualisation; and PyCO2SYS (Humphreys et al., 2022) for marine carbonate system calculations. Geographical features on maps were drawn using data that are freely available from Natural Earth (https://www.naturalearthdata.com/, last access: 23 October 2024).

3.1 Functional form of υ

Our first goal is to determine whether the newly proposed form υh (Eq. 20) can accurately represent the temperature sensitivity of seawater fCO2. To this end, we assess the accuracy of the approximations Ax and Tx made in developing Eq. (20) by comparing υh with calculations from a fully resolved marine carbonate system (Sect. 3.1.1). Next, we examine how well the different approaches to calculating υ agree with direct measurements; we do this for (1) laboratory experiments with measurements of fCO2 at multiple temperatures for a single seawater sample (Sect. 3.1.2) and (2) across a global dataset with pairs of measurements at two different temperatures (Sect. 3.1.3).

3.1.1 Accuracy of the approximations

We made several approximations to develop Eq. (20) (Sect. 2.1.3). First, all non-carbonate components of AT (Eq. 12) and the contribution of [CO2(aq)] to TC (Eq. 13) were neglected. Second, the simple integrated van 't Hoff equation (Eq. 17) was assumed to accurately represent how the various equilibrium constants vary with temperature. Third, when calculating bh from standard enthalpies of formation (Appendix A), these were assumed to be constant across the relevant temperature range. We must therefore check whether Eq. (20) can still capture the sensitivity of fCO2 to temperature accurately enough for our purposes before applying it to oceanographic data.

The first approximation above was also used to investigate the complementary question of how fCO2 varies with AT and TC under constant temperature (Humphreys et al., 2018). There, it was observed that the gradient of isocaps (i.e. lines of constant fCO2 through AT–TC phase space) was correlated with fCO2. The approximations Ax and Tx were used as the basis for a simplified representation of the marine carbonate system from which equations were derived to explain the observed correlation. This successful application to a closely related problem provides a first indication that the same approximations may also be suitable here.

We can do a more direct test using software like PyCO2SYS, which does not make any of the approximations above when calculating how fCO2 varies with temperature under constant AT and TC (Humphreys et al., 2022). Instead, the complete equations for AT and TC are used, and the equilibrium constants are parameterised with multiple temperature-, salinity- and pressure-sensitive terms, which implicitly include variations in the enthalpies of formation. Such calculations can therefore be used to quantify the effect of the approximations on the accuracy of Eq. (20). Equation (20) cannot be fitted directly to fCO2 data because υ represents the derivative with respect to temperature; instead, we need to fit Eq. (19) to obtain the unknown bh which can then be used in Eq. (20) for υh. If we use PyCO2SYS to calculate fCO2 across a range of temperatures with constant AT and TC, denoted fCO2(AT,TC), and then fit Eq. (19) to the results (Sect. 2.4), denoted fCO2(υp), the residuals from the fit should reveal any reduction in accuracy due to the approximations. Large residuals would suggest that at least one approximation was unsuitable for modelling υ, whereas small residuals would mean that the approximated system does still capture the main features of the t–fCO2 relationship that are needed to model υ.

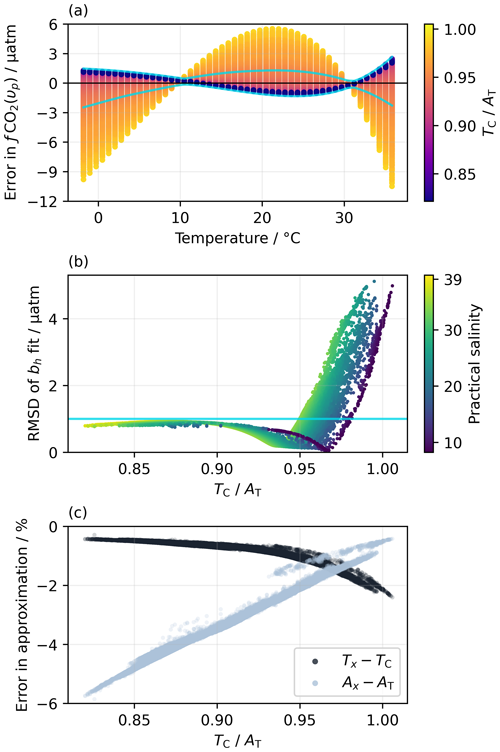

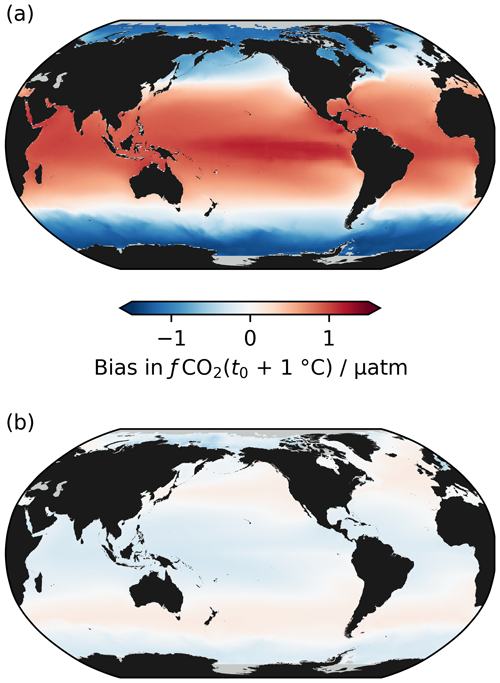

For over 97 % of the monthly mean grid points in OceanSODA-ETZH, the RMSD of the residuals between fCO2 calculated from Eq. (19) and from AT and TC is less than 1 µatm, with maximum deviations of ±2 µatm (Fig. 1). At lower (), fCO2(υp) is generally greater than fCO2(AT,TC) at low (<10 °C) and high (>30 °C) temperatures but less than fCO2(AT,TC) at intermediate temperatures (10–30 °C), but this switches to the opposite pattern at higher (Fig. 1a). We could not find a relationship between the switchover point, which has a very low RMSD, and some property of chemical buffering in seawater, although the value at which it occurs is correlated with salinity (Fig. 1b).

Figure 1(a) Residuals in fCO2 for the best fit of Eq. (19) to the fCO2 values calculated from a fully solved marine carbonate system at each monthly mean grid point in the OceanSODA-ETZH data product (Sect. 2.4), colour-coded by . Thus, each point in OceanSODA-ETZH appears as a line of points across panel (a) with constant . (b) Variation in the RMSD of the residuals shown in panel (a) with , colour-coded by practical salinity. Thus, each point in OceanSODA-ETZH appears as a single point in panel (b), which shows the RMSD of the corresponding line of points in panel (a). The blue lines in panels (a) and (b) correspond to an RMSD of 1 µatm: points with an RMSD of less than 1 µatm fall between the blue lines in panel (a) and below the horizontal blue in panel (b). Less than 3 % of the points have an RMSD greater than 1 µatm. (c) Variation in the percentage errors in the approximations Ax (Eq. 12) and Tx (Eq. 13) with at each monthly mean grid point in OceanSODA-ETZH.

As context for interpreting this <1 µatm RMSD, the uncertainty in fCO2 calculated from AT and TC that propagates from 0.1 % uncertainties in each of AT and TC (i.e. the GOA-ON climate quality goal; Newton et al., 2015) varies from 2 µatm at −1 °C to 9 µatm at 35 °C. The uncertainties in the equilibrium constants involved in this calculation are poorly known, but using the set proposed by Orr et al. (2018) roughly doubles the total uncertainty in calculated fCO2 given above. The <1 µatm RMSD between fCO2(υp) and fCO2(AT,TC) found for 97 % of the surface ocean is thus much smaller than the uncertainties in the marine carbonate system calculations themselves. It is also very similar to the RMSD of the linear and quadratic fits to the Takahashi et al. (1993) dataset (Sect. 2.1.2) and better than the GOA-ON climate quality goal for fCO2 measurements.

In the remaining <3 % of the global surface ocean, the RMSD can increase to over 5 µatm, which is less satisfactory but still within the GOA-ON weather quality goal (Newton et al., 2015). These higher RMSD values are constrained to values above 0.95 and to certain regions and seasons, primarily the Baltic Sea during winter and the near-coastal Arctic Ocean (Fig. S1). In these regions, the RMSD is correlated with several marine carbonate system properties, but one of the strongest correlations is with (Fig. 1b). The cause of the increased RMSD is likely inaccuracy in the approximation of Tx (Eq. 13). The fraction of TC comprised of [CO2(aq)], which is ignored in Tx, increases with (Fig. 1c). Consequently, the approximation that is constant across different temperatures (Eq. 16), which emerges from the definitions of Ax and Tx (Eqs. 12–15), becomes less accurate with increasing . The fraction of non-carbonate alkalinity, which is ignored in Ax, decreases with increasing , which makes Ax more accurate at higher (Fig. 1c); thus, Ax should not be the cause of the increased RMSD. The RMSD of the bh fit is positively correlated with the difference TC−Tx but negatively correlated with AT−Ax (Fig. S3), supporting the hypothesis that inaccuracy in Tx rather than Ax drives the increased RMSD observed at higher .

The ∼59 % of data points with (in dark purple in Fig. 1a) all have the same pattern of residuals with an RMSD that is virtually independent of and less than 1 µatm. Their independence from suggests that these residuals result from the additional temperature-dependent terms beyond from the van 't Hoff equation that are included in parameterisations of the equilibrium constants (e.g. Weiss, 1974; Dickson, 1990b; Lueker et al., 2000). Including such additional terms in Eq. (19) (and thus also in Eqs. 20–21) might allow it to better capture the pattern of ln (fCO2) variation with t, reducing the RMSD. Were υh to be adapted to include additional fitted parameters, the functional forms included should have a theoretical basis (e.g. Clarke and Glew, 1966) rather than being purely empirical, to ensure accurate uncertainty propagation (Sect. 3.2).

However, to include additional fitted parameters now would be premature. There are major differences between the different carbonic acid parameterisations (e.g. Fig. S2) that are not yet fully understood, and Fig. 1a and b would show different patterns if reproduced using a different parameterisation. Even though it is the parameterisation given by the best-practice guide (Dickson et al., 2007), it is still well-known that Lueker et al. (2000) does not perfectly represent the marine carbonate system to the accuracy with which we can measure it (e.g. Álvarez et al., 2020; Carter et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2023; Woosley, 2021; Woosley and Moon, 2023), and there are outstanding issues to resolve with, for example, the contribution of organic matter to total alkalinity (e.g. Ulfsbo et al., 2015; Hu, 2020; Kerr et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2024) and the borate-to-chlorinity ratio (e.g. Lee et al., 2010; Fong and Dickson, 2019). Furthermore, there are no robust uncertainty estimates for the equilibrium constants that can be propagated through to determine a meaningful uncertainty in υLu00 (Orr et al., 2018). The carbonic acid and other equilibrium constant parameterisations are not optimised for this derivative, emergent property (υ); direct measurements (like those of Takahashi et al., 1993), with which more subtle variations about the first-order form in Eq. (20) can be verified, are scarce (Sect. 3.1.2).

Even with these issues remaining unresolved, we conclude that, for over 97 % of the global surface ocean, Eq. (20) with all its approximations (Sect. 2.1.3) can capture the pattern of fCO2 sensitivity to temperature according to calculations from AT and TC with the carbonic acid dissociation constants of Lueker et al. (2000) to within an uncertainty of 1 µatm.

3.1.2 Direct measurements of υ

Having established how well υh from Eq. (20) agrees with calculations from a fully solved marine carbonate system, we next consider how these and other approaches compare with the scarce experimental evidence available.

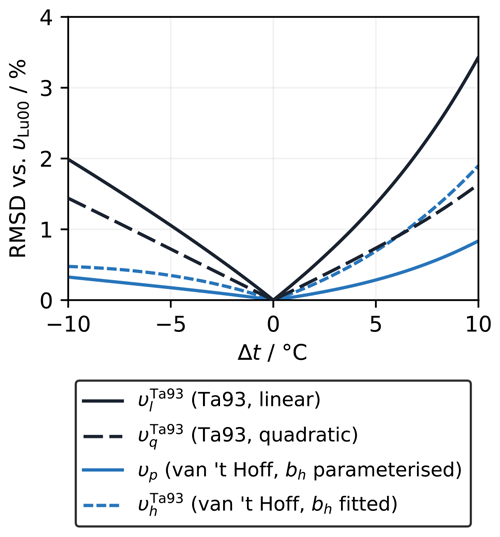

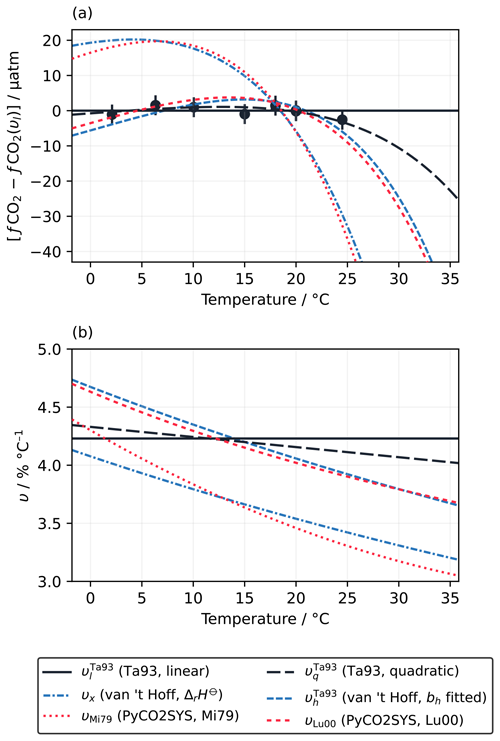

The linear (υl) and quadratic (υq) forms of Takahashi et al. (1993) both agree well with their own measurements, so it is not clear which (if either) is more appropriate. The RMSD for υq (0.9 µatm) is lower than that for υl (1.2 µatm), but this reduction is inevitable because υq has an extra adjustable coefficient (Eqs. 5–8). There is a meaningful difference between υl and υq only above ∼25 °C (Fig. 2a), where υq is lower, meaning that fCO2 would increase less with warming than suggested by υl. For example, adjusting from 25 to 35 °C would give an fCO2 that is about 17 µatm lower with υq than with υl.

Figure 2(a) Variation in fCO2 with temperature, normalised to the linear fit of Takahashi et al. (1993) (υl=4.23 % °C−1), according to the measurements of Takahashi et al. (1993) (Ta93; filled circles with vertical 1σ error bars) and the different fitted and theoretical values of υ computed under the conditions of the Takahashi et al. (1993) experiment (Sect. 2.1.2). υx is based on Eq. (18), using the theoretical bh of 25 288 J mol−1 (Appendix A), while uses Eq. (19) and the best-fit bh for the Takahashi et al. (1993) dataset of 28 995 J mol−1 (Sect. 2.1.3). (b) The values of υ calculated using each of the approaches shown in panel (a) as a function of temperature.

Next, we consider the form proposed here in Eq. (19). When bh is fixed to the value based on standard enthalpies of reaction (Sect. 2.1.3), so only the intercept (ch) can be optimised, the resulting curve υx has a rather different pattern that is inconsistent with the measurements (Fig. 2a). However, also allowing bh to be fitted to the measurements of Takahashi et al. (1993) () gives a pattern similar to υq, although with stronger curvature. Even though it agrees with the Takahashi et al. (1993) measurements less well than υl and υq do, with an RMSD of 2.9 µatm as opposed to ∼1 µatm, the υh line still falls within their uncertainty window. As for υq, the most significant deviation from υl occurs above 25 °C, where Takahashi et al. (1993) did not report any measurements. Adjusting from 25 to 35 °C would give an fCO2 that is about 45 µatm lower with than with υl.

There are 18 different parameterisations of the carbonic acid dissociation constants in PyCO2SYS v1.8.3, and each one gives a different pattern for υ. However, they are mostly negatively correlated with temperature, like υq and , so they all give lower fCO2 values at higher temperatures than υl does (Fig. S2). Two of the parameterisations are highlighted here.

The parameterisation of Millero (1979) (υMi79) agrees remarkably well with υx (Fig. 2). This parameterisation was designed for zero-salinity freshwater and excludes many of the non-carbonate equilibria that are active in seawater, such as that of borate.

The parameterisations that are (at least partly) based on the measurements of Mehrbach et al. (1973) fit the Takahashi et al. (1993) dataset better than those that do not, with the Lueker et al. (2000) parameterisation (υLu00) having one of the best fits (RMSD=2.6 µatm) and falling within the uncertainty of the measurements (Fig. 2a). The pattern of υLu00 is very similar to (Fig. 2b). The similarity was expected, given the results discussed in Sect. 3.1.1 and the of ∼0.92 for the sample used by Takahashi et al. (1993). However, the similarity above 25 °C is more remarkable in this case, as the υh curves in Sect. 3.1.1 were fitted to data spanning the full temperature range from −1.8 to 35.83 °C, whereas there were no data above 24.5 °C (nor below 2.1 °C) to guide the shape of the fitted curve here. Thus even without having a wide enough temperature range for the data to show convincing curvature in υ, the extrapolation of Eq. (20) still matches the calculations with PyCO2SYS very well, unlike υl and υq.

There are two main reasons for the differences between υx and or, equivalently, between υMi79 and υLu00. First, and υLu00 include additional equilibria that are not present in υx and υMi79. Some of these extra equilibria are explicitly part of the alkalinity equation in PyCO2SYS (e.g. borate); others are implicit, such as the formation of and ion pairs (Millero and Pierrot, 1998), which are incorporated within [] and in PyCO2SYS (Humphreys et al., 2022). The approximation that all non-carbonate species are negligible within AT (Eq. 12) is thus more accurate for υx and υMi79 (hence their mutual agreement) than it is for and υLu00. Second, the van 't Hoff equation with standard enthalpies of reaction predicts the temperature sensitivity of thermodynamic equilibrium constants. However, chemical equilibria in seawater are modelled using stoichiometric equilibrium constants, which have an additional temperature dependency related to the major ion composition and ionic strength of the solution (Pitzer, 1991). Both reasons would affect and υLu00 (and hence their deviation from υx) but not υMi79, which is consistent with υx.

The strong agreement between υx and υMi79 strengthens our conclusion from Sect. 3.1.1 that the approximations made in deriving Eq. (20) are valid for representing the first-order form of υ. It also means that under certain low-salinity conditions, Eq. (18) can be used directly with ΔrH⊖ values from the literature and no further fitting to quantify υ accurately with respect to calculations with an equilibrium model (PyCO2SYS). The strong agreement between and υLu00 suggests that the extra equilibria and ionic strength effects can be adequately accounted for by adjusting the value of bh and without changing the form of the t–ln (fCO2) relationship.

It is unfortunate that the dataset of Takahashi et al. (1993) has a maximum temperature of 24.5 °C, because extra data points above 25 °C could unambiguously distinguish between the different forms of υ. At lower temperatures, the differences between the forms are similar in size to the uncertainty of the measurements, so many more highly accurate measurements would need to be conducted to robustly distinguish between the forms (Fig. 2a). The Kanwisher (1960) measurements covered an even narrower temperature range from 11 to 21.5 °C, which is also insufficient to convincingly show non-linearity.

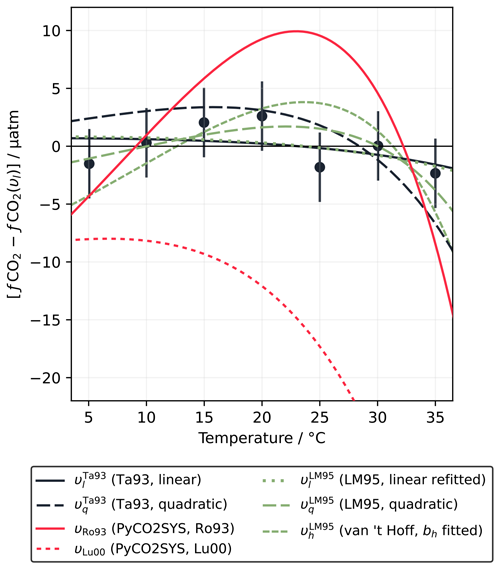

One published dataset does cover a wider temperature range, with seven measurements of a single sample from 5.05 to 35 °C (Lee and Millero, 1995). These measurements can be fitted well with both the linear and quadratic forms (Eqs. 5 and 6), with RMSD values of 1.8 µatm (linear) and 1.5 µatm (quadratic). Lee and Millero (1995) reported a constant υl of 4.26 % °C−1, stating that the difference between this and the value of Takahashi et al. (1993) was due to a different for the sample measured (0.85 versus ∼0.92). As with the Takahashi et al. (1993) dataset, fits less well than either υl or υq, with an RMSD of 2.8 µatm, although the fitted curve again falls within the uncertainty window of the data points (±3 µatm). However, in this case, is completely different from the calculation with the Lueker et al. (2000) carbonic acid dissociation constants (Fig. 3). It also predicts significantly less deviation from υl or υq than in the Takahashi et al. (1993) case.

Figure 3Variation in fCO2 with temperature, normalised to the linear fit of Lee and Millero (1995) (υl=4.26 % °C−1), according to the measurements of Lee and Millero (1995) (LM95; filled circles with vertical 1σ error bars) and the different fitted and theoretical values of υ computed under the conditions of the Lee and Millero (1995) experiment. uses Eq. (19) and the best-fit bh for the Lee and Millero (1995) dataset of 30 794 J mol−1 (Sect. 2.1.3). The line for υLu00 continues to decrease after exiting the figure, reaching −40 µatm at 35 °C.

The fitted bh value of 30 794 J mol−1 for is unusual, falling outside the range fitted across the entire monthly mean OceanSODA-ETZH data product (25 139 to 30 731 J mol−1; Sect. 2.4; Fig. S2a). Based on the AT, TC and salinity reported by Lee and Millero (1995), and with the carbonic acid dissociation constants of Lueker et al. (2000), we would have expected a bh of 29 825 J mol−1. Unlike Takahashi et al. (1993), which is not inconsistent with Eq. (20) but lacks data at high enough temperatures to convincingly support or reject it, the Lee and Millero (1995) dataset is clearly inconsistent with Eq. (20).

However, the Lee and Millero (1995) measurements are also inconsistent in a number of other ways not related to Eq. (20). We refitted the Lee and Millero (1995) dataset with the linear form (Eq. 5) and found a lower RMSD (1.6 µatm) using the υl value of 4.23 % °C−1 from Takahashi et al. (1993). It appears that Lee and Millero (1995) minimised residuals in ln (fCO2) in their fit rather than minimising residuals in fCO2; the latter approach returns almost exactly the Takahashi et al. (1993) value of 4.23 % °C−1. Minimising residuals in ln (fCO2) implicitly assumes that uncertainty in fCO2 is a constant fraction of the fCO2 value rather than an absolute fixed amount, but Lee and Millero (1995) reported the “reproducibility” as ±3 µatm, not as a percentage. While, at first glance, it may seem like an improvement that fitting the data consistently with the uncertainty brings the υl value in line with Takahashi et al. (1993), this in fact contradicts the reasoning of Lee and Millero (1995) themselves in that a different value is expected because of the rather different . For to be the same as that of Takahashi et al. (1993), either TC or AT would need to be adjusted by over 160 µmol kg−1, which is far more than permitted by the measurement accuracy.

The Lee and Millero (1995) dataset is also not consistent with PyCO2SYS calculations. As mentioned above, the carbonic acid dissociation constants of Lueker et al. (2000) do not fit well at all, with an RMSD of 20 µatm (Fig. 3). While Lee and Millero (1995) claim that their data are “thermodynamically consistent” with the constants of Roy et al. (1993) and Goyet and Poisson (1989), neither of these fits very well, with both having an RMSD of ∼6 µatm (Fig. 3). However, they did acknowledge that more studies of the temperature sensitivity of the marine carbonate system are needed, pointing to possible problems with the Weiss (1974) formulation for CO2 solubility, which is still used in PyCO2SYS (Humphreys et al., 2022).

In summary, while comparisons with the experimental datasets do not rule out Eq. (20), they are less convincing than the comparisons with PyCO2SYS calculations in Sect. 3.1.1. For the Takahashi et al. (1993) dataset, it is plausible that extra measurements at higher temperatures could have revealed significant deviations from linearity, as predicted independently by both PyCO2SYS and Eq. (20), although the linear υl still fits the data more closely than υh does. The Lee and Millero (1995) dataset, which does include higher-temperature measurements, does not support this. This latter dataset does feature a number of other inconsistencies that could cast doubt on its accuracy, but, alternatively, there may be some aspect of the equilibrium chemistry of CO2 in seawater that is missing from or incorrectly parameterised within existing models such as PyCO2SYS. It is not possible to draw a reliable conclusion either way from only these two small datasets. We need a much bigger body of measurements to be able to robustly distinguish between the different possible forms of υ.

3.1.3 Global data compilation

The Wanninkhof et al. (2022a) compilation provides much more data (∼2000 data points) with which to test the different temperature adjustment approaches, including across variations in salinity and carbonate chemistry (AT and TC). The compilation consists of fCO2 measured in discrete seawater samples at 20 °C (irrespective of the in situ temperature), along with fCO2 measured at (or close to) the in situ temperature with a continuously flowing underway system at closely corresponding times and locations. Independent measurements of AT and TC are also available for many of the data points.

This dataset goes some way towards fixing the data scarcity problem mentioned in Sect. 3.1.2, but it is still not a complete substitute for additional experiments like that of Takahashi et al. (1993). In particular, each sample has measurements of fCO2 at only two different temperatures, so the form of the t–fCO2 relationship between those two points cannot be determined for any individual sample. Instead, we must infer the suitability of different forms of υ from how well they work across the entire dataset.

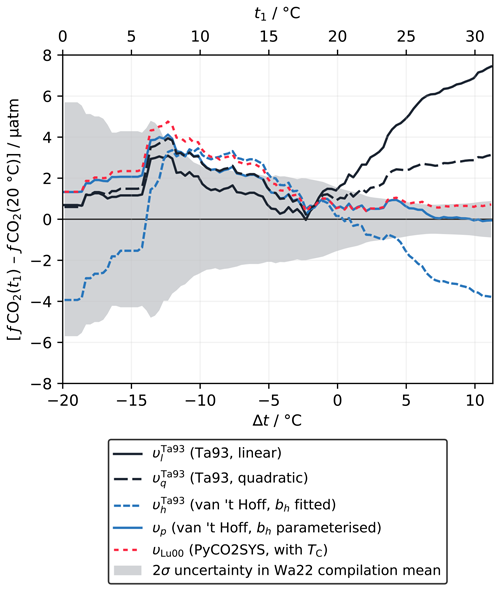

We adjusted the fCO2 at 20 °C from the discrete samples to the temperature of the in situ measurement using five different approaches: the linear (υl) and quadratic (υq) equations of Takahashi et al. (1993) (Sect. 2.1.2); the van 't Hoff form with bh constant as fitted to the Takahashi et al. (1993) dataset (; Sect. 2.1.3) and parameterised as a function of temperature, salinity and fCO2 (υp; Sect. 2.4); and calculation with PyCO2SYS using TC as the second known parameter and the carbonic acid dissociation constants of Lueker et al. (2000) (υLu00). To compare the accuracy of these adjustments, we computed the rolling mean of the differences between fCO2 adjusted from 20 °C to the in situ temperature and fCO2 measured directly at the in situ temperature for each approach, using a ±4 °C window (Fig. 4). Like Wanninkhof et al. (2022a), we excluded outliers falling more than ±2 standard deviations from zero, which was 1.4 % of the total data points.

Figure 4Difference between fCO2 adjusted from 20 °C to the in situ temperature and a direct measurement at (or close to) the in situ temperature, shown as a rolling mean (±4 °C window) for each adjustment approach, for the data in the Wanninkhof et al. (2022a) compilation (Wa22). The shaded area shows the 2σ uncertainty in the rolling mean, centred about zero, which is a function of the number of data points within each interval and virtually identical for every approach.

For negative Δt there are relatively few data (about 14 % of the dataset), such that the different rolling mean lines overlap and mostly fall within the large uncertainty window (Fig. 4). It is not possible to meaningfully distinguish between the different approaches. All appear to overestimate fCO2(t1) for Δt from about −14 to −5 °C, by a similar amount to each other, with some falling just outside the uncertainty window of the rolling mean. The consistency between the different approaches here is expected, as they are most similar to each other in the corresponding t1 range from about 10 to 20 °C (Fig. 2a). The minor deviations for negative Δt are therefore probably due to the sparsity of data in this temperature range, which means that errors due to measurement uncertainty and imperfect co-location of samples are not averaged out. We would expect these deviations from zero to diminish were more data added to the compilation.

The Δt range above 0 °C contains the majority of the dataset (86 %) and sufficient data for the approaches to diverge clearly from each other and for some to move well outside the uncertainty window (Fig. 4). Here, the linear form (υl) significantly overestimates fCO2(t1) as Δt increases. Wanninkhof et al. (2022a) tried fitting υl directly to this data compilation to improve the accuracy of the adjustment but were not able to fix this issue. Instead, they concluded that calculations with a fully resolved carbonate system were still required for Δt greater than about 1 °C, recommending the Lueker et al. (2000) carbonic acid dissociation constants with the Uppström (1974) borate-to-chlorinity ratio for the best agreement (υLu00). Like υl, the quadratic form (υq) overestimates fCO2(t1) for positive Δt. The error is about half of that for υl but still well outside the uncertainty window. The van 't Hoff form with constant bh () has a similar error to υq but with the opposite sign; i.e. fCO2(t1) is underestimated. However, the van 't Hoff form with a variable, parameterised bh (υp) gives almost perfect agreement, even for the largest Δt, performing even better than the calculation with a fully resolved carbonate system (υLu00), which also falls just within the uncertainty window.

This analysis shows that the van 't Hoff form is at least as capable as the other approaches of adjusting fCO2 to different temperatures across this data compilation. When variability in bh is accounted for by the parameterisation proposed in Sect. 2.4, which is completely independent of this data compilation, this approach (υp) can be used for accurate Δt adjustments of up to at least 10 °C. More data for negative Δt are still essential to improve our confidence in this conclusion across the full temperature range found in the ocean.

Part of the motivation for the new approach to υ developed here (Sect. 2.1.3) was to avoid needing to know a second marine carbonate system parameter when adjusting fCO2 to different temperatures. υp with fixed bh does not meet this requirement, because, as for υl and υq, the adjusted fCO2 values are not accurate enough. Initially it appears that υp does meet the requirement – its only inputs are fCO2, temperature and salinity (Eq. 35), and it is equally or more accurate than calculations with PyCO2SYS (Fig. 4). However, arguably, the need for a second parameter has been sidestepped rather than truly eliminated. The parameterisation for bh works because, to first order, bh, υh and fCO2 are closely correlated with the ratio but less sensitive to the absolute values of either TC or AT (Goyet et al., 1993; Wanninkhof et al., 2022a). In other words, the fCO2 term in the parameterisation acts as a proxy for , implicitly providing the information about TC and AT necessary to calculate υ.

It would be possible to parameterise υl and υq across the ocean, as we have done for υh (i.e. υp), which would improve their agreement with the data compilation too. However, we have already established that there is no theoretical reason to expect the t–ln (fCO2) relationship to be linear, especially at higher t, and Wanninkhof et al. (2022a) tried fitting υl to this dataset directly without satisfactory results. Further benefits of υh over υq are discussed in Sect. 3.2 on uncertainty propagation.

3.2 Experimental uncertainty

We performed Monte Carlo simulations of the Takahashi et al. (1993) experiment (Sect. 2.2.2) to determine the uncertainty in υ computed from that dataset using the linear (υl; Eq. 5), quadratic (υq; Eq. 6) and van 't Hoff (; Eq. 19) fits.

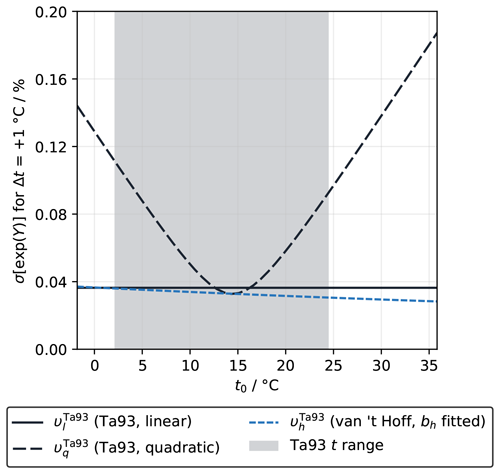

Were the linear fit a valid representation of the t–ln (fCO2) relationship, then the 1σ uncertainty in experimentally determined υl would be 0.035 % °C−1. The biggest contributor (0.028 % °C−1 on its own) is the precision of the fCO2 measurement, with 0.020 % °C−1 from systematic bias in fCO2 alone. Systematic biases can affect υ because it is the gradient of the natural logarithm of fCO2 (Eq. 1), which is a non-linear transformation. Temperature uncertainties have a much smaller impact, with 0.001 % °C−1 uncertainty in υ arising from t precision alone and no effect from t bias. Propagating through to exp (Υl) for a Δt of +1 °C gives an uncertainty of just under 0.04 % (Figs. 5 and S4). Following Eq. (4), the percentage uncertainty in exp (Υ) propagates through to the same percentage uncertainty in the adjusted fCO2 value at t1, so this calculation is most relevant for understanding how uncertainties in υ affect temperature-adjusted fCO2 values.

Figure 5The 1σ uncertainty in exp (Υ) for °C, which is equal to the percentage uncertainty in fCO2 at t1 caused by uncertainty in υ, due to experimental uncertainties in t and fCO2 in the Takahashi et al. (1993) dataset only and fitted with the linear (dotted line; Eq. 5) and quadratic (dashed line; Eq. 6) forms as well as the fitted van 't Hoff form (solid line; Eq. 19). The shaded area shows the range of t from the Takahashi et al. (1993) experiment, while the full t-axis range matches OceanSODA-ETZH. The uncertainty in υ itself as a function of temperature has a virtually identical pattern to that shown here for exp (Υ) (e.g. an uncertainty in exp (Υ) of 0.04 %, with °C, corresponds to an uncertainty in υ of about 0.04 % °C−1; Fig. S4).

With the quadratic fit (Eq. 6), the 1σ uncertainty in the slope (bq) is 0.127 % °C−1, whereas the corresponding value in the squared term (aq) is °C−2, and there is a covariance between these of °C−3. Propagating through to υq and exp (Υq) gives an uncertainty that is similar to that for the linear fit in the middle of the t range but is up to 4 times greater in colder and warmer waters (Figs. 5 and S4). It is essential to include the covariance term for propagation; failure to do so wrongly inflates the final uncertainty.

The van 't Hoff fit has a 1σ uncertainty in the bh of 216.4 J mol−1. Propagating through to and gives a similar uncertainty to that for υl, decreasing slightly with increasing temperature (Figs. 5 and S4).

The uncertainties calculated here, for °C, are all lower than the climate quality target uncertainty for seawater fCO2 measurements of 0.5 % proposed by GOA-ON (Newton et al., 2015). This means that this uncertainty component alone would not cause an fCO2(t1) value with Δt up to ±1 °C to breach this target, regardless of which form was correct, although it is probably not small enough to ignore in a complete uncertainty budget. Also, its contribution scales roughly in proportion with Δt; therefore, for greater Δt, this component would become a greater part of the overall uncertainty in fCO2(t1).

Why do the different approaches have different uncertainties and how do we choose which approach and corresponding uncertainty to use? The linear and van 't Hoff forms both appear to have similarly low uncertainties, but the temperature adjustments that they predict differ from each other by more than the apparent uncertainty windows, especially above 25 °C (Fig. 2). The quadratic form has a completely different uncertainty profile with apparently much greater uncertainty at the edges of the temperature range (Fig. 5). The assumption implicit within any uncertainty calculation – that the model being fitted to the data is valid and that all of its adjustable parameters are truly unknown and necessary – is key to resolving this.

As we have shown in Sect. 3.1, it is not consistent with existing models of the marine carbonate system for υ to be constant and independent from temperature, so the uncertainty calculated for υl is valid only under this premise. In other words, the assumptions that “υ is constant” and “υ varies with temperature” are mutually incompatible. This is how υl and can deviate from each other by more than their apparent uncertainties.

It makes sense that υq has greater uncertainty than υl and , as υq has an extra coefficient to be constrained by the same number of data points. Given more data at higher t, υq could plausibly be fitted to a shape almost identical to υh, yet it would still appear to have greater uncertainty for this reason. When using υq, we accept that there is some curvature in the t–ln (fCO2) relationship, but we implicitly assume that we do not know what form that curvature takes, other than it can be represented by some second-order polynomial. The adjustable parameters that represent the curvature are thus constrained empirically only by the available data, leading to much higher apparent uncertainty towards its edges. However, we now know that, to first order, υ should follow a particular curvature that can be represented with only one adjustable parameter (bh); it is not an unknown that must be found empirically. The lower uncertainty in and relative to υq and exp (Υq) is therefore more realistic (Fig. 5), with the caveat that more experimental work is still needed to determine whether the expected relationship from Eq. (20) can be produced in laboratory measurements (Sect. 3.1.2).

While small, this uncertainty component is probably not negligible for the most accurate analyses. More independent reproductions of the Takahashi et al. (1993) experiment, ideally including temperatures up to 35 °C, could reduce this component into a negligible term. However, this component reflects only the experimental uncertainties in fCO2 and temperature. To use this value as the total uncertainty in υ and/or exp (Υ) would be to assume that the single sample measured by Takahashi et al. (1993) is representative of the global ocean. It does not account for spatiotemporal variability in υ, which we discuss in Sect. 3.3.

3.3 Spatial and temporal variability

3.3.1 Variability in υLu00

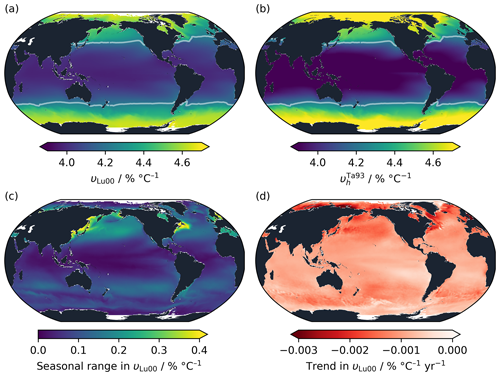

The time-averaged theoretical value of surface ocean υLu00 in OceanSODA-ETZH (Gregor and Gruber, 2021) follows a latitudinal distribution, with lower values near the Equator (Fig. 6a). The range in υLu00 is more than 15 % of its mean, from less than 4.0 % °C−1 to over 4.6 % °C−1. The pattern is dominantly driven by temperature. The other variables (AT, TC and salinity) together act in the opposite sense, slightly reducing the latitudinal gradient in υLu00. This can be seen from the distribution of , which uses the constant bh found by fitting to the Takahashi et al. (1993) dataset (Sect. 2.1.3) and has a similar but stronger latitudinal gradient (Fig. 6b). A counterintuitive consequence of this is that, were the Takahashi et al. (1993) experiment to be repeated systematically across the globe, fitting with a linear equation at each location, this would return the opposite pattern of υl to what we see in Fig. 6a: higher values near the Equator and lower near the poles. The variability in υl as determined following Takahashi et al. (1993) is independent from the original in situ temperature of the sample, so the experiment would reveal variability in υ only due to the non-thermal parameters.

Figure 6Spatial and temporal variability in υ in OceanSODA-ETZH using the Lueker et al. (2000) parameterisation of the carbonic acid dissociation constants. (a) Theoretical υLu00 calculated from AT, TC and auxiliary variables, averaged through time across the entire OceanSODA-ETZH dataset. (b) calculated from OceanSODA-ETZH temperature using the bh value fitted to the Takahashi et al. (1993) measurements, again averaged through time. Panels (a) and (b) use the same colour scale, and the white contour in both panels shows the Takahashi et al. (1993) linear fit value of υl=4.23 % °C−1. (c) Mean seasonal range and (d) multi-decadal trend in υLu00.

The seasonal range in υ is a similar size to, although slightly less than, the spatial range in its time-averaged value. It is less than 0.2 % °C−1 across most of the open ocean, reaching a maximum of just over 0.4 % °C−1, or around 10 % of the mean, in some near-coastal areas with strong seasonal variability in temperature and/or (Fig. 6c).

Together, the spatial and seasonal variability in υLu00 has a standard deviation of 0.23 % °C−1. This could be considered to represent the 1σ uncertainty in using a constant υl globally, keeping in mind that it has strong regional systematic biases rather than being randomly distributed. It is significantly greater than the apparent experimental uncertainty in υl or of around 0.04 % °C−1 (Sect. 3.2). Experiments like that of Takahashi et al. (1993) should be sufficiently accurate to detect the variability in υ if conducted at different locations around the global ocean. However, this also means that spatiotemporal variability that is unaccounted for would lead to uncertainty in υ and exp (Υ) that is several times greater in practice than that computed in Sect. 3.2.

On multi-decadal timescales, υ has been decreasing globally at an average rate of 0.001 (Fig. 6d). The decrease has been primarily driven by increasing with a smaller contribution from warming of the surface ocean. This trend is consistent with that identified by Wanninkhof et al. (2022a), and it should lead to a minor decrease in the temperature dependency of surface ocean fCO2 while atmospheric CO2 levels continue to rise.

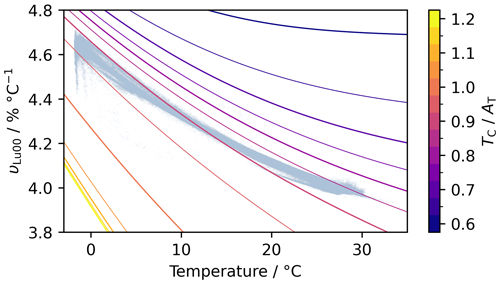

Wanninkhof et al. (2022a) pointed out that υ is greater at lower temperatures and lower at lower and that temperature and are, to first order, negatively correlated in the global surface ocean (largely due to the influence of temperature on CO2 solubility), leading to them having opposing effects on υ and thus reducing its variability. We find that this effect does reduce spatial variability in υ, although by 30 % at most relative to a constant- scenario. For a temperature change from −1.7 to 30 °C, the main body of the OceanSODA-ETZH monthly mean data product has a range in υLu00 from about 3.97 % to 4.60 % °C−1, whereas at a constant of 0.9, υLu00 varies from 3.85 % to 4.72 % °C−1 (Fig. 7). However, this partial cancellation of the effect of temperature on υ by is not relevant for making temperature adjustments; it does not mean that the temperature sensitivity of υ can be ignored or is any less important. This is because adjustments are made on single samples under constant . The sensitivity of υ to temperature for any individual sample is not lessened by the negative correlation between temperature and observed across the global dataset. In other words, coupled temperature– variations in the surface ocean reduce the spatiotemporal variability in υ under in situ conditions, but they do not affect by how much υ changes with temperature for a particular sample. Consequently, the apparent reduced variability in υ is relevant only for small (e.g. Δt<1 °C) temperature adjustments.

Figure 7Each coloured line shows how υLu00 varies with temperature at a constant , with TC always at the median value of the monthly mean OceanSODA-ETZH data product (i.e. 2045 µmol kg−1). increases from 0.6 (dark purple, top right) to 1.2 (yellow, bottom left). The light-blue points in the background show all monthly mean data from OceanSODA-ETZH.

3.3.2 Components of υ

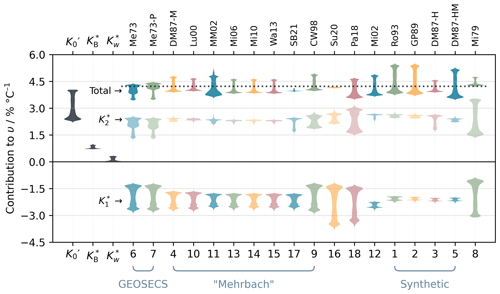

Variability in υ through space and time arises primarily from the temperature dependence of the equilibrium constants of the marine carbonate system. Across the contemporary global surface ocean, the biggest contributor to υ is , the solubility constant for CO2, which typically represents 58 %–89 % of total υ (Fig. 8). The carbonic acid equilibrium constants and contribute a similar size effect on υ to each other and slightly less than . However, the contribution is always negative, whereas the contribution is always positive; therefore, they partly cancel each other out. Smaller contributions are made by the borate (9 %–21 %) and water (1 %–8 %) equilibria ( and , respectively). All other equilibrium constants have a negligible influence on υ in the contemporary ocean, although they might become important at pH values closer to their pK.

Figure 8Violin plot of the contributions of each equilibrium system to υ as distributed across the monthly averaged OceanSODA-ETZH data product. From the left, the first three violins show the contributions of the CO2 solubility constant () and the borate () and water () equilibria. The remaining columns show the contributions of the carbonic acid dissociation constants and as well as the total υ for each parameterisation in PyCO2SYS v1.8.3. The horizontal dashed line through the “Total” group is at the Takahashi et al. (1993) linear fit value (υl=4.23 % °C−1). The colours are to help the eye track the groups vertically; they do not have any further meaning. The lower horizontal axis shows the option code within PyCO2SYS for the carbonic acid constants, while the upper axis shows an abbreviation of the corresponding study (presented as “option code/abbreviation” in the following): 1/Ro93 – Roy et al. (1993); 2/GP89 – Goyet and Poisson (1989); 3/DM87-H, 4/DM87-M and 5/DM87-HM – refits of various combinations of Hansson (1973a, b) and Mehrbach et al. (1973) by Dickson and Millero (1987); 6/Me73 and 7/Me73-P – GEOSECS fits of Mehrbach et al. (1973); 8/Mi79 – Millero (1979), for freshwater; 9/CW98 – Cai and Wang (1998); 10/Lu00 – Lueker et al. (2000); 11/MM02 – Mojica Prieto and Millero (2002); 12/Mi02 – Millero et al. (2002); 13/Mi06 – Millero et al. (2006); 14/Mi10 – Millero (2010); 15/Wa13 – Waters and Millero (2013); 16/Su20 – Sulpis et al. (2020); 17/SB21 – Schockman and Byrne (2021); 18/Pa18 – Papadimitriou et al. (2018).

Each parameterisation of the carbonic acid dissociation constants gives a different υ distribution, but there are some similarities (Fig. 8). We could not identify a link between the functional forms of the parameterisations (i.e. which combinations of t and salinity terms were used) and the distributions shown in Fig. 8; rather, the type of seawater, specific dataset(s) and methodology used to determine the constants were the main controls.