the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Wave boundary layer model in SWAN revisited

Rodolfo Bolaños

Xiaoli Guo Larsén

Mark Kelly

In this study, we extend the work presented in Du et al. (2017) to make the wave boundary layer model (WBLM) applicable for real cases by improving the wind-input and white-capping dissipation source functions. Improvement via the new source terms includes three aspects. First, the WBLM wind-input source function is developed by considering the impact of wave-induced wind profile variation on the estimation of wave growth rate. Second, the white-capping dissipation source function is revised to be not explicitly dependent on wind speed for real wave simulations. Third, several improvements are made to the numerical WBLM algorithm, which increase the model's numerical stability and computational efficiency. The improved WBLM wind-input and white-capping dissipation source functions are calibrated through idealized fetch-limited and depth-limited studies, and validated in real wave simulations during two North Sea storms. The new WBLM source terms show better performance in the simulation of significant wave height and mean wave period than the original source terms.

- Article

(6380 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

The accuracy of spectral ocean wave models depends on the forcing from wind, water level, currents, etc. It also depends on the source terms and numerical methods (Ardhuin, 2012). In deep water conditions, the source terms are reduced to the wind-input source function (Sin), wave-breaking dissipation source function (Sds), and nonlinear four-wave-interaction source function (Snl). In a previous study (Du et al., 2017), a wave boundary layer model (WBLM) was implemented in the third-generation Simulating WAves Nearshore (SWAN) ocean wave model (Booij et al., 1999) to improve the wind-input source function of Janssen (1991, hereafter JANS); this was done by considering the momentum and kinetic energy conservation at each level in the wave boundary layer. It was shown that the new Sin improves wave simulations in idealized fetch-limited conditions. Because the evolution of wave spectra depends on the difference between source and sink terms, the change of Sin has to be followed by the tuning of the parameters in Sds (Cavaleri, 2009). Du et al. (2017) simply recalibrated the white-capping dissipation parameters of Komen et al. (1984, hereafter KOM) to be proportional to the WBLM Sin (Babanin et al., 2010) and wind speed at 10 m (U10) (Melville and Matusov, 2002). Such a method works in idealized fetch-limited conditions when the winds do not change over time. However, in real cases, wind speed and direction vary in time. Also, wave breaking is related to wave properties such as wave steepness, rather than explicitly dependent on wind speed (e.g., Komen et al., 1994). Moreover, in coastal areas, the bottom friction and depth-induced breaking dissipation become important and they influence the shape of wave spectra. Consequently, Sin and Sds are also modified by the shallow-water effect. Therefore, the description of the new Sin and Sds in shallow water also needs to be investigated before they are used in real simulations.

Theoretical models of wave-breaking dissipation have been extensively reviewed by Komen et al. (1994), Young and Babanin (2006a), and Cavaleri et al. (2007), and can be classified into white-capping models (Hasselmann, 1974), saturation-based models (e.g., Phillips, 1985), probabilistic models (e.g., Longuet-Higgins, 1969; Yuan et al., 1986; Hua and Yuan, 1992), and turbulent models (Polnikov, 1993). Among them, white-capping and saturation-based models are widely used in ocean wave models such as WAM (Komen et al., 1994), Simulating WAves Nearshore (SWAN) (Booij et al., 1999), WAVEWATCH III (Tolman and Chalikov, 1996), and MIKE 21 SW (Sørensen et al., 2005). White-capping models consider the effect of downward-moving whitecaps doing work against the upward-moving waves. Parameterization of white-capping dissipation can be found in, e.g., Komen et al. (1984), Bidlot et al. (2007), and Bidlot (2012); the dissipation at all frequencies is taken to be proportional to the mean wave steepness defined by a mean wave number and the significant wave height. The saturation-based models assume saturation exists in the equilibrium range of the wave spectrum, and the dissipation rate is proportional to the saturation at any given frequency. Therefore, the dissipation at each frequency is proportional to the local wave steepness or local saturation. Latter studies, however, suggest a two-phase behavior of wave-breaking dissipation (Babanin and Young, 2005; Young and Babanin, 2006a): Sds should be a function of the spectral peak plus a cumulative frequency-integrated term at higher frequencies due to dominant wave breaking. Considering the complexity of wave-breaking processes, recent studies tend to combine the two types of Sds together. Alves and Banner (2003) and van der Westhuysen et al. (2007) used a saturation-based model multiplied by a KOM-shaped model to account for the longwave–shortwave and wave–turbulence interactions. Banner and Morison (2010) introduced a breaking probability function to the saturation-based model of Phillips (1985). Ardhuin et al. (2010), Babanin et al. (2010), and Zieger et al. (2015) added a cumulative term to a saturation-based model. Such combined Sds values are proven to be robust in wave simulations, globally to coastal areas (Ardhuin et al., 2012; Ardhuin and Roland, 2012; Leckler et al., 2013).

However, as more physical processes are being taken into account, expressions of Sds become more complex and need more tuning parameters; e.g., the Sds of Ardhuin et al. (2010) needs up to 18 parameters, which makes it difficult to adjust when there is modification of other source terms. The present study aims at finding a proper dissipation source function that is suitable for the new WBLM Sin. Therefore, instead of introducing more physics into Sds, numerical adjustment is applied to the KOM dissipation (Komen et al., 1984). The reason that we chose the KOM Sds is that it has been shown to be successful when used with different wind-input source functions in SWAN (Snyder et al., 1981; Komen et al., 1984; Janssen, 1991; Larsén et al., 2017), and because the formulation is so flexible that its total magnitude and spectral distribution can be easily tuned with Cds and Δ in Eq. (10). Du et al. (2017) has shown that numerical adjustment to the KOM Sds can be used for the WBLM Sin, to reproduce the fetch-limited wave growth curve of Kahma and Calkoen (1992). Moreover, Ardhuin (2012) showed that Sds of the KOM type and saturation-based type (Phillips, 1985) can be adjusted to give very similar behavior. However, we found that using only the KOM Sds within the WBLM produces a too-high energy level at frequencies higher than the spectral peak (f>fp), and this problem can be solved by using a cumulative dissipation term according to Ardhuin et al. (2010).

In this paper, the improvement of WBLM Sin, the revised Sds, and the numerical algorithm changes to the model are presented in Sect. 2. Then, the new pair of Sin and Sds is calibrated in idealized fetch-limited and depth-limited studies, and validated in real-case storm simulations in the North Sea. These numerical experiments are described in Sect. 3, and the results are presented in Sect. 4. Wave parameters such as significant wave height, mean period, peak wave period, and spectral shape are validated using point measurements of deep and shallow waters. Sin and Sds of KOM and JANS are also examined as a benchmark reference for these storms. As mentioned before, wave growth depends on the difference between source and sink terms as well as numerical discretization methods, especially in real cases. Therefore, it is difficult to distinguish whether an improvement of a specific wave parameter, such as significant wave height, is due to the improvement of Sin or Sds. An evaluation of the WBLM Sin was presented in Du et al. (2017) in an idealized fetch-limited wave growth study, where the wave growth rate and the drag coefficient calculated from Sin are compared with measurements. However, this paper mainly focuses on the application of WBLM for real applications, so that the overall effect of the new WBLM Sin and Sds is emphasized.

2.1 The wind-input source function

According to Du et al. (2017), the growth rate (βg) of the WBLM wind-input source function is expressed as

where N(σ,θ) is the action density spectrum, θ and θw are the wave and wind directions, Cβ is the Miles parameter (Miles, 1957), ρw is the water density, and c is the phase velocity of waves. τt(z) is the local turbulent stress, which is equal to the total stress, τtot, minus the wave-induced stress, τw(z). The Miles parameter Cβ is described as a function of the non-dimensional critical height, λ:

where κ=0.41 is the von Kármán constant, and J=1.6 is a constant. In Du et al. (2017), the expression of the non-dimensional critical height λ for Miles' parameter (Eq. 2) is derived by the assumption of a logarithmic wind profile following Janssen (1991), and it is expressed as

where g is the gravity acceleration, α=0.008 is a wave age tuning parameter according to Bidlot (2012), z0 is the roughness length. However, it is found that using Eq. (3) causes numerical instability in some cases. This is because, within the WBL, the wind profile is not logarithmic under the impact of waves (Du et al., 2017). Using a logarithmic wind profile (Eq. 3) not only slows down the computation but could also fail in converging in some cases. Therefore, when applying WBLM Sin, the expression of λ also needs to be changed to adjust to the new wind profile. Here, we follow Miles (1957)'s procedure to drive an approximate expression for λ. In Miles (1957), the non-dimensional critical height is defined as

where k is the wave number, zc is the critical height where the wave phase velocity (c) equals the wind speed component in the phase velocity direction ,

where θ−θw is the angular separation between wind and wave directions. We assume that, in the vicinity of the critical height (zc), the wind profile can be approximately described as locally logarithmic:

where is the local friction velocity. In the vicinity of the critical height, wind speed at any other heights z can be expressed as

where is a local effective roughness. Introducing Eqs. (7)–(5), we have wind speed at the critical height:

The critical height is calculated by combining Eqs. (7) and (8):

Considering the shallow-water dispersion relation, , with h the water depth, the combination of Eqs. (4) and (9) results in the non-dimensional critical height for any direction:

It is found that Eq. (10) tends to underestimate wave growth at low frequencies. We used the same method as that used in WAM (Bidlot, 2012) and added a wave age tuning parameter (α=0.011) to shift the wave growth towards lower frequencies:

2.2 White-capping dissipation source function

The white-capping dissipation expression of KOM (Komen et al., 1984; Janssen, 1991; Bidlot et al., 2007) in SWAN is written as

where is the frequency spectra. Since the WBLM wind-input and dissipation source functions are designed mainly for the wind sea, it is necessary to reduce the swell impact to the white-capping dissipation. In this study, the mean radian frequency 〈σ〉 and mean wave number 〈k〉 are modified according to Bidlot et al. (2007) to put more emphasis on the high frequencies:

where is the variance of the sea surface elevation. The choice of the two dissipation parameters, Cds and Δ, is different for different wind-input source functions. For example, for KOM Sin, Cds=2.5876 and Δ=1; for JANS Sin, Cds=4.5, and Δ=0.5; for WBLM Sin in Du et al. (2017), Δ=0.1, and Cds in Sds is related to Sin to make sure

where

where U10 is wind speed at 10 m, and is a non-dimensional energy. As discussed in the introduction, a dissipation parameter that is strongly dependent on wind speed as in Eq. (12) only works in idealized fetch-limited cases but will in principle not work in real cases because wave breaking depends on wave state rather than wind. Here, we explore the use of some wave parameters to replace U10 and Sin in Eqs. (11) and (12) to get rid of the direct dependence on wind speed. We derive the relationship between U10, m0, peak frequency (fp), and fetch (x) from the three non-dimensional parameters, namely non-dimensional energy (), non-dimensional peak frequency (), and non-dimensional fetch (). The fetch dependence of and can be written as

where, in Kahma and Calkoen (1992) (composite condition), , B=0.9, C=2.1804, . According to Eq. (12), U10, , and can be expressed as functions of m0, fp, and g:

where U10, , and are replaced by U′, E′, and x′ since they are parameterized variables. The dissipation coefficient Cds in Eq. (10) can be obtained by fitting the Cds calculated from Eqs. (11) and (12) with U′ and x′ from Eq. (13):

The form and parameters in Eq. (14) will be obtained in the fetch-limited study in Sect. 4.1. To increase the robustness of the wave modeling in the case of unusual-shaped spectra, the peak frequency fp in Eq. (13) is replaced by 0.866〈f〉 according to Komen et al. (1994) who uses kp=0.75〈k〉, where is the mean frequency. The use of 〈f〉 may cause uncertainty in estimating fp, especially in, e.g., bimodal wave cases. Considering the model performs quite well during the two storm simulations in Sect. 4.3, during which bimodal waves probably exist, we assume that this uncertainty is relatively small.

To reduce the energy level at high frequencies, a cumulative term is added to the dissipation source functions. The cumulative dissipation term () follows Ardhuin et al. (2010), but the directional dependence of dissipation rate is not considered:

where Ccu=1.0 is a dissipation parameter, Br=0.0012 is a saturation threshold, rcu=0.5 is the ratio of the maximum frequency where dissipation of long waves influences short waves, Cg is the group velocity, and B(f) is the local saturation (van der Westhuysen et al., 2007):

2.3 Improvement of the numerical algorithm

Considering the expensive cost of WBLM code in Du et al. (2017), improvement of the numerical algorithm of the WBLM (Du et al., 2017) was done in the following aspects.

-

The unnecessary calculations in the high frequencies were reduced. The WBLM uses 10 Hz as the maximum frequency, which is only being used for very young waves. Usually, the WBLM does not have to solve such high frequencies when the energy is so small that their contribution to the total wave-induced stress is negligible. Therefore, in the new code, the WBLM only solves the active frequency range which is dynamically changing with the wave spectrum. Although the maximum frequency is dynamically changing, all the active frequencies are solved, so there is no influence on the result. Such an adjustment reduces approximately half of the computation time in the idealized fetch-limited study in Sect. 3.1.

-

The standard calculation in SWAN, a sweeping technique is used for the directional propagation of the waves, needs to be swept four times for each time step. Such a sweep is not necessary for the calculation of WBLM because the WBLM has to integrate over all directions of the spectra. Therefore, WBLM only calculates once per time step.

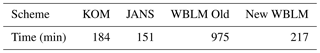

With the above mentioned refinement, the WBLM is now about 5 times faster than the previous version in Du et al. (2017). It is still slower than KOM and JANS, but it is fast enough for real applications. The averaged calculation time during an idealized fetch-limited study is listed in Table 1, including KOM, JANS, the previous WBLM of Du et al. (2017) (WBM Old), and the new WBLM in this paper. All the setups are the same as those in Sect. 3.1, except JANS uses frequency number ranges from 38 to 54 for different wind speed conditions, while the other schemes use 73 frequencies.

3.1 Idealized fetch-limited study

The revised dissipation parameter (Eq. 14) in Sds together with the new non-dimensional critical height as in WBLM Sin were first calibrated in the idealized fetch-limited wave growth experiments with the same model setup as in Du et al. (2017). Here, we briefly describe the model setup. We use the one-dimensional SWAN. The fetch is between 0 and 3000 km, with the spatial resolution changing gradually from 0.1 to 10 km. The wave spectrum ranges from 0.01 to 10.51 Hz, and the frequency discretization was logarithmic with a frequency exponent of 1.1, which results in 73 frequencies. We use 36 directional bins with a constant spacing of 10∘. SWAN initializes from zero spectrum and runs for 72 h with a time step of 1 min. U10 ranges from 5 to 40 ms−1 and keeps constant during the 72 h simulation.

The calibration process is carried out in three steps. In Step 1, we run the model using the white-capping dissipation parameter as in Du et al. (2017) (Eqs. 11 and 12) in the idealized fetch-limited study. Since we added a cumulative dissipation source term, the parameters in Eq. (12) have to be changed into Eq. (16) so as to best fit to the Kahma and Calkoen (1992) fetch-limited wave growth curves:

In Step 2, the real form and parameters in Eq. (14) will be obtained by analyzing and fitting the Cds with x′ and U′, which are calculated in Step 1. Finally, the best fit in Step 2 may not be the best choice for the wave model. Therefore, we selected several representative fitting parameters out of dozens of groups through idealized fetch-limited study as the final choice.

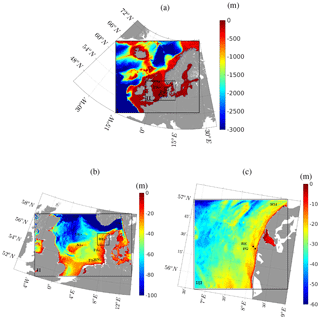

Figure 1SWAN domain for “Reducing the uncertainty of near-shore wind estimations using wind lidars and mesoscale models” (RUNE) storm simulation, with domains I at 9 km resolution, II at 3 km resolution, and III at 600 m resolution. Panels (a, b, c) show the bathymetry at domain I, II, and III. Bathymetry data are interpolated from EMODnet digital terrain model (DTM) 1∕8 arcmin data. The five measurement sites, RUNE (RE), Fjaltring (FG), Hanstholm (HM), A121 (A1), Väderöarna (VA), Heligoland north (HN), Fino-1 (F1), Fino-3 (F3), Sleipner-A (SA), and Ekofisk (EK), are shown as black dots.

3.2 Idealized depth-limited study

In addition to the idealized fetch-limited study, the revised WBLM source terms are also tested in depth-limited wave growth experiments to check if the new source terms perform well with the interaction of the other source terms in the wave model, including the bottom friction and depth-induced wave-breaking dissipation source functions. Following SWAN (2014), we use JONSWAP (Hasselmann et al., 1973) bottom friction with a bottom friction coefficient, Cb=0.038 m2 s−3, and Battjes and Janssen (1978) depth-induced wave-breaking source function with a breaker parameter, γ=0.8.

In the depth-limited wave growth experiments, we take the measurements of Young and Babanin (2006b) as reference for validation, because they not only provided detailed wind, wave, and water depth information but also provided wave spectrum measurement from capacitance wave probes up to 10 Hz (Young et al., 2005). Zijlema et al. (2012) conducted similar depth-limited wave growth experiments for the calibration of the bottom friction parameter in SWAN, but they did not compare the wave spectrum. Zijlema et al. (2012) selected 10 representative cases from the data presented in Young and Babanin (2006b). We add three more cases because the wave spectra in these three cases are also presented in Young and Babanin (2006b). This ends up with 13 cases in all, which are numbers 1, 11, 17, 23, 28, 30, 32, 58, 61, 63, 82, 83, and 87 in Table 1 of Young and Babanin (2006b). Among them, numbers 1, 11, 28, 32, and 87 have wave spectrum records for model validation. In all 13 cases, the water depth ranges from 0.89 to 1.1 m, and the wind speed ranges from 5.7 to 15 ms−1. The fetch is set to 20 km with a spatial resolution of 0.1 km to ensure the fetch is long enough, and the wave growth is limited by the water depth. The frequency and directional discretization are same as those in the fetch-limited study. SWAN initializes from zero spectrum and runs for 24 h (we found 24 h is long enough for the wave development in the shallow-water conditions in this study), with a time step of 1 min. Two pairs of Sin and Sds are tested, namely KOM (Snyder et al., 1981; Komen et al., 1984) and the revised WBLM in this study.

3.3 Real case study in the North Sea

The new WBLM Sin and Sds are validated during two winter storms in the North Sea. Wind and wave measurements are obtained during the “Reducing the uncertainty of near-shore wind estimations using wind lidars and mesoscale models” (RUNE) project (Floors et al., 2016b). Simultaneous wind and wave measurements from lidar and buoys are available from November 2015 to January 2016. The experiment was conducted on the west coast of Jutland, Denmark, with an average water depth of 16.5 m. Details about the wind and wave measurements can be found in Floors et al. (2016b, a, c), Bolaños (2016), and Bolaños and Rørbæk (2016). Besides the standard wave parameters such as significant wave heights, peak wave period, and mean wave periods, the two-dimensional wave spectra E(f,θ) are also available, which allows us to validate more detailed aspects of the source functions. During the RUNE period, two storms passed the measurement site on 28 November 2015 and 12 August 2015. Wave simulations were done during this period with the three pairs of source terms (KOM, JANS, and WBLM). Besides the measurement from the RUNE project, point wave measurements at Fjaltring, Hanstholm, A121, Väderöarna, and Heligoland north from NOOS (https://noos.bsh.de/, last access: 15 June 2017) FINO-1 and FINO-3 from FINO (http://fino.bsh.de, last access: 3 April 2018) and Sleipner-A and Ekofisk from eKlima (http://sharki.oslo.dnmi.no, last access: 17 November 2016) during the simulation period are also used for model validation. The locations of these measurement sites are shown in Fig. 1a, b, and c.

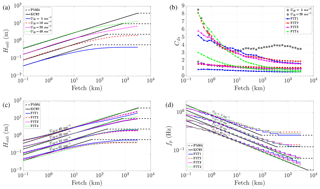

Figure 2Hm0 as a function of fetch after 72 h of simulation in different wind speed conditions using Eq. (16) as the white-capping dissipation parameter (a). Cds as a function of fetch after 72 h of simulation in different wind speed conditions using Eq. (16), and fitted Cds using FIT1 to FIT4 (b). Hm0 and fp as a function of fetch using white-capping dissipation parameters from FIT1 to FIT4 (c, d).

SWAN is forced by the National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP) Climate Forecast System version 2 (CFSv2) 10 m wind (Saha et al., 2011). The quality of CFSv2 10 m wind speed and direction is evaluated with measurements in Fig. 6a–b, and it has been shown to be good quality for wave simulations in the North Sea in many previous studies (Bolaños et al., 2014). Therefore, the hourly CFSv2 data may be considered reasonable wind forcing, though it may not be accurate in the presence of highly fluctuating wind on scales smaller than 1 h, e.g., Larsén et al. (2017). SWAN uses three nested domains, with a resolution downscaling from 9 to 3 km and 600 m (Fig. 1a). Open boundaries for SWAN are set to 0. The shortest fetch of the observation points is larger than 1000 km according to the wind direction during the storm. According to the fetch-limited study in Sect. 4.1, the fetch is long enough for the waves to develop. The bottom friction and depth-induced wave-breaking source functions for the real case study are same as the depth-limited wave growth studies. Bathymetry data are obtained from the EMODnet digital terrain model (DTM) with a spatial resolution of 1∕8 arcmin. Note that most of the observations are located in the coastal areas in the North Sea, except Sleipner-A, A121, and Ekofisk (Fig. 1b, c). The water depth of most sites is less than 30 m, except Sleipner-A and Ekofisk, which are relatively deeper, with water depth around 80 and 60 m, respectively. SWAN initializes from zero spectrum, and the first 24 h output are not included in our analysis. The first storm peak is about 72 h after the model initializes to make sure the duration of the simulation is long enough. The frequency discretization was logarithmic with a frequency exponent of 1.1, and the lowest frequency was set to 0.03 Hz. For the KOM and WBLM source terms, a cut-off frequency of 10.05 Hz is used, giving a total of 61 frequencies; for JANS source terms, the cut-off frequency is set to 0.57 Hz to make sure the simulation is stable, giving a total of 31 frequencies. We used 36 directional bins and a 5 min time step. A summary of the constants and model setups used for all the experiments in Sect. 3 is given in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

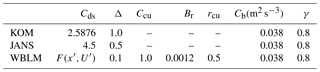

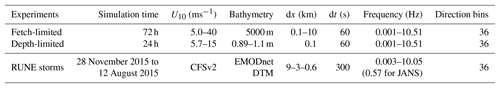

Table 2Constants used for all the experiments in Sect. 3. Cds and Δ are white-capping dissipation parameters in Eq. (10); is the new dissipation parameter for WBLM in Eq. (14); Ccu, Br, and rcu are cumulative dissipation parameter for WBLM in Eq. (15); Cb and γ are JONSWAP (Hasselmann et al., 1973) bottom friction and Battjes and Janssen (1978) depth-induced wave-breaking parameters.

Table 3A summary of model setups for all the experiments in Sect. 3. dx is the spatial resolution and dt is the time step of SWAN in seconds.

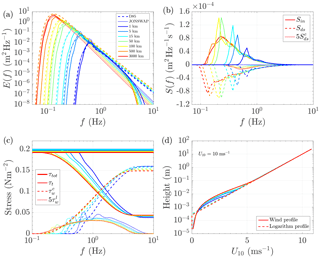

Figure 3Wave spectrum (a), wind-input and dissipation source terms (b), stress distribution over frequencies (c), and wind profile (d) calculated from WBLM, in 10 ms−1 wind speed conditions at different fetches after 72 h simulation, in the fetch-limited wave growth study. The dashed lines and dotted lines in panel (a) are the wave spectrum parameterization from D85 (Donelan et al., 1985) and JONSWAP (Hasselmann et al., 1973); the solid lines are from WBLM. The solid, dashed, and dotted lines in panel (b) are the WBLM wind-input (Sin), white-capping dissipation (Sds), and 5 times the cumulative dissipation () source functions, respectively. Thick solid, thin solid, dashed, and dotted lines in panel (c) are the total stress (τtot), turbulent stress (τt), cumulative wave-induced stress (), and 5 times the local wave-induced stress () from WBLM. The solid lines in panel (d) are calculated from WBLM, and the dashed lines are the relative logarithm wind profiles extended from wind speed at 10 m elevation.

4.1 Idealized fetch-limited study

The significant wave height (Hm0) calculated from Step 1 of the idealized fetch-limited study using Eqs. (11) and (16) is shown in Fig. 2a. The Kahma and Calkoen (1992) wave growth curves are also shown as solid black lines for reference. Note that Kahma and Calkoen (1992) curves come from data with limited wind speeds (U10≤25 ms−1) and fetches (x≤300 km), and we linearly extend them to broader ranges. The Hm0 calculated from Step 1 (solid colored lines in Fig. 2a) agrees with Kahma and Calkoen (1992) wave growth curves for fetches x≤10 km. But it tends to underestimate Hm0 for fetches x>10 km. Therefore, in Step 2, we only fit the Cds in the first 10 km and extend its application for longer fetches. The Cds calculated from Step 1 for wind speed U10=5 ms−1 and U10=20 ms−1 is shown in Fig. 2b as black circles and black rectangles. Here, we try to speculate the form of Eq. (14) based on the distribution of Cds from Step 1 in Fig. 2b. First, Cds has a clear dependence on U10. We found that in 10 ms−1 wind speed conditions, the simulated Hm0 follows the Kahma and Calkoen (1992) curves quite well in all fetches, while in the other wind speed conditions, the model underestimates Hm0 when U10<10 ms−1 or overestimates Hm0 when U10>10 ms−1. Therefore, we take 10 ms−1 as reference, and there should be a term in the Cds equation. Second, Cds depends on the fetch; considering the fetch dependence is logarithmic (the horizontal coordinate of Fig. 2b is logarithmic), there should be a ln(x) term in the Cds equation. Considering that a log-transformed quantity must be unitless, we use the non-dimensional fetch ln(x′) instead of ln(x). Therefore, we assume Cds in Eq. (14) has the following form:

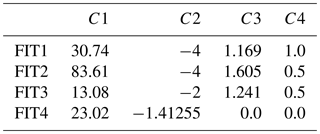

where C1, C2, C3, and C4 are parameters to be determined by fitting the Cds calculated from Step 1. Directly using the four parameters may be easier to fit, but it requires more effort to use or change it in real applications. Therefore, instead of finding a random combination of the four parameters that gives the least square error, we prefer to reduce the number of fitting parameters based on our understanding of the role of the two terms, namely ln(x′) and in Eq. (16). We use fixed value for the power on ln(x′) and . By testing with a resolution of 1, and with a resolution of 0.1, we choose C2=2 and 4, C4=0.5 and 1 as representative values. With the values of C2 and C4 provided, we fit C1 and C3 with the data from Step 1 and end up with the first three groups of fitting parameters listed in Table 4 (FIT1 to FIT3). FIT4 in Table 4 is an improvement for FIT3 which will be described latter. The fitted Cds using FIT1 to FIT4 at different wind speed conditions is shown in Fig. 2b as colored lines with circles and rectangles representing wind speed.

Table 4Four groups of fitting parameters (FIT1, FIT2, FIT3, and FIT4) for Eq. (16).

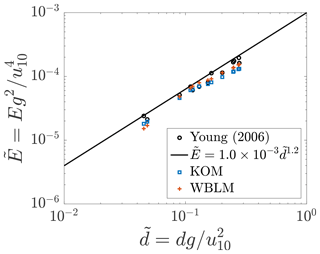

Figure 4Observed (black circles) and parameterized (black line) non-dimensional wave energy for fully developed waves in shallow water as a function of non-dimensional depth (Young and Babanin, 2006b) and SWAN results with KOM (blue squares) and WBLM (red crosses) source terms after 24 h simulation.

The four groups of parameters (FIT1 to FIT4 in Table 4) are applied in SWAN in the fetch-limited study, and the results are shown in Fig. 2c, d. The effect of the term in Eq. (16) can be seen from the comparison between FIT1 and FIT2. The fitted Cds, simulated Hm0, and fp of FIT1 and FIT2 are shown in Fig. 2b, c, d as blue solid and red solid lines with circles and rectangles representing wind speed. Although significant difference of Cds between C4=1.0 (FIT1) and C4=0.5 (FIT2) is seen in Fig. 2b, the resulting Hm0 and fp show a relatively small difference. In low wind speed conditions (U10=5 and 10 ms−1), C4=1.0 (blue solid lines in Fig. 2c, d) results in larger Hm0 (smaller fp) than C4=0.5 (red solid lines in Fig. 2c, d). In high wind speed conditions (U10=20 and 40 ms−1), C4=1.0 underestimates Hm0 (overestimates fp) more than C4=0.5 in long fetches (x>10 km).

Figure 5One-dimensional wave spectrum measured by (Young and Babanin, 2006b) (black circles) for fully developed waves in shallow water and the results from SWAN with KOM (blue lines) and WBLM (red lines) source functions after 24 h simulation.

The effect of the ln(x′)C2 term can be seen from the comparison between FIT2 and FIT3, the red solid and magenta dashed lines in Fig. 2b, c, d. The impact of C2 to Hm0 and fp is much weaker than C4. Using C2=2 (magenta dashed lines in Fig. 2c, d) results in slightly larger Hm0 (smaller fp) than C2=4 (red solid lines in Fig. 2c, d) in long fetches (x>10 km), which results in larger white-capping dissipation, smaller Hm0, and larger fp.

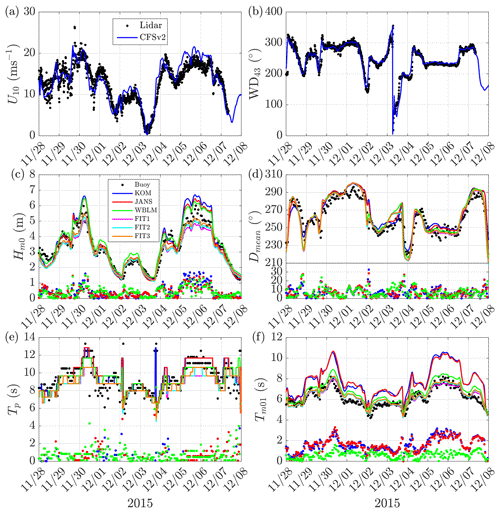

Figure 6Time series during two winter storms in the RUNE project. (a) The 10 m wind speed from CFSv2 and measurements calculated from a logarithm wind profile from lidar measurements at 43, 50, 62, 82, and 100 m. (b) Wind direction from CFSv2 and lidar measurement at 43 m. (c) Modeled significant wave height (solid lines) in comparison to buoy measurements (black dots); colored dots show the absolute error. (d) Mean wave direction. (e) Peak wave period. (f) Mean wave period.

FIT1–FIT3 tend to underestimate Hm0 (overestimate fp) in long fetches (x>10 km). In the real case study in Sect. 4.3, it will be shown that such an underestimation of Hm0 failed in capturing large waves in real storm simulations. Therefore, we continuously reduce the value of C2 and C4 until the large waves are captured in both the idealized fetch-limited study and real case study, which results in the parameters of FIT4 (hereafter WBLM). In FIT4, C4=0.0 means that term is disappeared in Eq. (16). From Eq. (13), we found that both U′ and x′ could be written in the form of , which indicate that the function of the U′ term could be replaced by changing the parameters in the x′ term. This can be seen from the green lines in Fig. 2b that, without the term, Cds still follows different curves in different wind speed conditions.

Figure 7Time series of Hm0 at Fjaltring (FG), Hanstholm (HM), A121 (A1), Väderöarna (VA), Heligoland north (HN), Fino-1 (F1), Fino-3 (F3), Sleipner-A (SA), and Ekofisk (EK) during the two winter storms in the RUNE project. Observations are shown in black dots, modeled Hm0 using different source terms are shown in colored solid lines, and the corresponding colored dots show the absolute error between modeled results and observations.

Figure 3a shows the wave spectrum from WBLM (solid lines) in 10 ms−1 wind speed conditions after 72 h simulation in comparison to the spectrum parameterization of D85 (Donelan et al., 1985) (dashed lines) and JONSWAP (Hasselmann et al., 1973) (dotted lines) with the fetch dependence from Kahma and Calkoen (1992). Detailed equations for D85 and JONSWAP are listed in Appendix Appendix A. The results from the WBLM source term generally follow the shape of the D85 and JONSWAP spectra, but they tend to underestimate the energy at low frequencies at fetches x≥10 km.

Figure 8One-dimensional wave spectrum from buoy measurements at RUNE with all available data during the two storms (a); panels (b–d) are simulated with different source terms. The colors of the lines represent different times. The black solid lines in each panel are the envelope lines to mark the upper and lower bounds of the measurement data.

The D85 spectra at short fetches (e.g., 1 km) have less energy at high frequencies (e.g., f>1 Hz) than at long fetches (e.g., 3000 km). On the contrary, JONSWAP and WBLM spectra have more energy at short fetches than at long fetches at high frequencies. The D85 spectra have a f−4 shape at high frequencies, while JONSWAP has a f−5 shape. The high-frequency part of WBLM spectra is between f−4 and f−5. Figure 3b shows the source term distribution of wind-input (Sin, solid lines), white-capping dissipation (Sds, dashed lines), and 5 times the cumulative dissipation (, dotted lines) source functions at different fetches indicated by color legends in Fig. 3a. instead of is used to better visualize the cumulative dissipation source term. As the waves grow older, the Sin values at high frequencies become smaller, and values become larger, which may explain why the WBLM spectra have more energy at short fetches than at long fetches at high frequencies. Figure 3c shows the corresponding stress distribution within the wave boundary layer. Here, we also use (dotted lines) instead of for the purpose of visualizing the local wave-induced stress. Short fetch waves contribute more surface stress than long fetch waves at high frequencies, while they contribute less stress than long fetch waves at low frequencies. The total wave-induced stress depends on the integration of at all frequencies, which results in waves with a fetch of 5–15 km having the highest total wave-induced stress, waves with a fetch of 1 km having lower total wave-induced stress, and waves with a fetch of 3000 km having the lowest wave-induced stress. Accordingly, total wind stress (τtot, thick solid lines) at 5–15 km is larger than that at 1 and 3000 km because of the impact of the waves. Figure 3d shows the wind profiles within the wave boundary layer calculated by WBLM. Wind profiles are rather different in different wave development stages, which reveals that it is necessary to take the wave-induced wind profile variation into account in the estimation of the critical height in Sect. 2.1.

4.2 Idealized depth-limited study

Figure 4 shows the non-dimensional wave energy as a function of non-dimensional depth for fully developed waves in shallow waters after 24 h simulation, with the measurements of Young and Babanin (2006b) as reference. In comparison, results from KOM source terms are also shown. Both the WBLM (red crosses) and KOM (blue squares) show close agreement with the measurements (black circles).

The one-dimensional wave spectrum in the depth-limited experiment is further examined after 24 h simulation in Fig. 5a–e for different wind speed and depth conditions, with the measurements of Young and Babanin (2006b) as reference. Both models capture the peak of the wave spectrum. However, KOM (blue lines) tends to underestimate the energy level at high frequencies. On the contrary, the energy level of WBLM (red lines) at high frequencies closely follows the measurements.

4.3 Two storms during the RUNE project

During the two RUNE storms on 28 November 2015 and 12 August 2015, wave simulation was done with SWAN forced by CFSv2 wind. The performance of KOM, JANS, and WBLM source terms are evaluated with buoy measurements in terms of significant wave height Hm0, mean wave direction Dmean, peak period Tp, mean period Tm01, and one-dimensional wave spectrum. Figure 6 shows the simulated time series of Hm0, Dmean, Tp, and Tm01 in comparison to buoy measurements at RUNE. To see the impact of different parameters of the WBLM white-capping dissipation source function to the wave simulation, results from FIT1 to FIT3 are also shown. Similar to the conclusions in the idealized fetch-limited study in Sect. 4.1, these parameters significantly underestimate high waves. Only FIT4 (here WBLM) can be used for real wave simulations to capture the high waves.

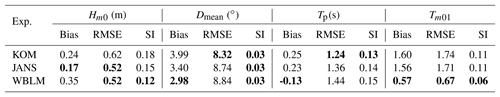

Table 5Statistics of simulated significant wave height (Hm0), mean wave direction (Dmean), and peak (Tp) and mean (Tm01) wave period in comparison to buoy measurements at the RUNE site on 28 November 2015 and 12 August 2015. The statistics include mean difference (bias), root mean square error (RMSE), and scatter index (SI). In each column, the values of smallest absolute errors are indicated with bold text.

Now we compare the performance of the new WBLM with KOM and JANS source terms. For Hm0, Dmean, and Tp, all the modeled time series generally follow the general trends of measurement data. The biggest error of Hm0 happens at the two storm peaks. The three source terms overestimate the Hm0 during the peak at about 1 m (15 %). WBLM gives slightly better Hm0 during the peak than KOM and JANS. But it tends to underestimate Tp during the storm peaks. WBLM predicts Tm01 significantly better than KOM and JANS. Note that the buoy Tm01 is calculated from the frequency range of 0.005 to 0.64 Hz, JANS is from 0.03 to 0.58 Hz, and KOM and WBLM are from 0.03 to 0.63 Hz. A summary of the statistics is listed in Table 5, and the definitions of the statistics are given in Appendix Appendix B. WBLM generally provides better results for Hm0 and Tm01 than KOM and JANS. All the three source terms have similar accuracy in predicting Dmean. WBLM is slightly less accurate in predicting Tp than KOM and JANS.

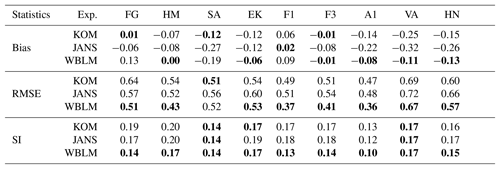

Table 6Statistics of simulated significant wave height (Hm0) in comparison to measurements at Fjaltring (FG), Hanstholm (HM), A121 (A1), Väderöarna (VA), Heligoland north (HN), Fino-1 (F1), Fino-3 (F3), Sleipner-A (SA), and Ekofisk (EK) on 28 November 2015 and 12 August 2015. The statistics include mean difference (bias), root mean square error (RMSE), and scatter index (SI). In each column, the values of smallest absolute errors are indicated with bold text.

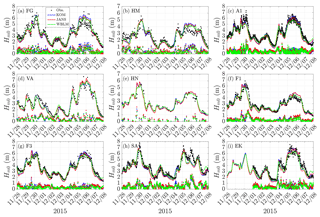

The time series of Hm0 at another nine measurement sites, including Fjaltring (FG), Hanstholm (HM), A121 (A1), Väderöarna (VA), Heligoland north (HN), Fino-1 (F1), Fino-3 (F3), Sleipner-A (SA), and Ekofisk (EK) in the North Sea during the two storm simulations, are shown in Fig. 7. The relative statistics are listed in Table 6. Considering the statistics of mean difference (bias), root mean square error (RMSE), and scatter index (SI), WBLM generally gives better Hm0 than KOM and JANS for most of the sites. However, in contrast to RUNE, WBLM tends to underestimate the largest waves during storm peaks in the open-ocean sites, e.g., the storm peak at A121 (Fig. 7c), Sleipner-A (Fig. 7g), and Ekofisk (Fig. 7i).

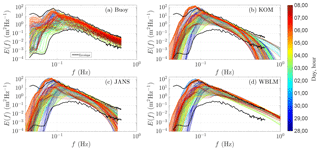

The one-dimensional wave spectrum during the whole simulation period at the RUNE site is presented in Fig. 8. The colored lines in Fig. 8a show the data from buoy measurements, and the black envelope lines are used to mark the upper and lower bounds of the measurement data. The colored lines in Fig. 8b, c, d are from SWAN simulations using KOM, JANS, and WBLM source terms, and the black envelope lines are the same as those in Fig. 8a. The three simulations generally capture the shape of the measured spectrum. In comparison to the measurements, KOM and JANS tend to overestimate the energy around the spectral peak, while WBLM gives better energy estimation around the spectral peak. Both KOM and JANS show a leveling off of energy at frequencies higher than about 0.3 Hz, while the measurement and WBLM do not, which may explain the failure of KOM and JANS in simulating Tm01. However, seemingly WBLM tends to overestimate the energy at frequencies higher than the peak, which needs further investigation.

This study first calibrates the WBLM wind-input and dissipation source terms in idealized fetch-limited cases and further validates the model in idealized depth-limited cases and two real storm cases. In the selected cases, it is proven that the revised WBLM source terms can be used for real cases and can provide certain wave properties better than the original ones in SWAN, such as KOM and JANS. However, two storm cases do not represent all the wave conditions in the ocean; e.g., bimodal waves, slant waves, and swells are not analyzed in detail in this study. Therefore, more comprehensive analysis and validations from different data resources such as satellite data are still necessary in further studies.

The main difference between WBLM and previous wind-input source functions in SWAN is that the WBLM explicitly considers physics such as the growth rate reduction of short wind waves in the presence of long waves. This effect mainly affect the young waves. Moreover, the modification of the dissipation coefficient is also focused on the young wind waves. Therefore, the introduction of WBLM source terms to SWAN mainly improves the young wind waves which are usually found in the coastal areas. This can be seen in Fig. 7. The significant wave height (Hm0) at the storm peak at the open-sea sites, including A121 (Fig. 7c), Sleipner-A (Fig. 7h), and Ekofisk (Fig. 7i), is underestimated by WBLM in comparison to measurements, while at the other coastal sites, the Hm0 at the storm peak is captured quite well by WBLM. Relating the underestimation of Hm0 at the storm peak at the open-sea sites and the underestimation of Tp at RUNE (Fig. 6e), these defects maybe due to the inaccuracy of the calculation of nonlinear four-wave interactions at low frequencies or the overestimation of swell dissipation. Here, we simply added a positive wave age tuning parameter α in Eq. (10) following Bidlot et al. (2007) to shift the wave growth towards a lower frequency, which may not enough to overcome these defects. A more exact method for the calculation of nonlinear four-wave interactions and an independent swell dissipation such as that used by Ardhuin et al. (2010) is needed in the future study.

As mentioned in Du et al. (2017), one of the biggest strengths of WBLM is in the estimation of the air–sea momentum flux. Since this study mainly concerns its behavior in the wave simulations, the air–sea momentum flux (or roughness length/drag coefficient) is not included in the analysis. A future study with the focus on its momentum flux estimation was carried out and presented in Du (2017) chap. 8, and it was found that the WBLM method provides reliable roughness length estimation in terms of the magnitude and the spatial distribution of it in coastal shallow water in comparison to point measurements and the Envisat Advanced Synthetic Aperture Radar (ASAR) backscatter.

The WBLM source terms is found to improve the prediction of the mean period significantly. Through analyzing the frequency spectra, it is speculated to be caused by an improved description of the high-frequency part of the spectrum. However, the energy from WBLM at high frequencies seems too high in comparison to measurements. Therefore, the energy distribution in the high-frequency range needs to be further investigated. One possible way of reducing this overestimated energy at high frequencies is by tuning the parameters in the cumulative dissipation source function (e.g., Ccu in Eq. 15). However, the tuning of these parameters has to be followed by the tuning of the other parameters in the source terms including wind-input, white-capping, nonlinear four-wave interactions, etc. to make sure that both the stress estimation and the wave simulation are all satisfied.

Janssen (1991)'s wind-input source function was found by Du et al. (2017) and Du (2017) chap. 5 to be wrongly implemented in SWAN. We found that in the calculation of the contribution of high-frequency tail to wave stress code, the judgment of whether the growth rate coefficient of a frequency (βg) over all directions is zero, is called before calculating βg in all the directions. This may disregard some of the high-frequency waves and therefore reduces the calculated wave stress. We also tried our best to change the code following the description of Bidlot et al. (2007) and by implementing some functions from WAM code (https://github.com/mywave/WAM, last access: 21 June 2017) to SWAN. Since this study is mainly focused on the usage of WBLM, a detailed analysis of Janssen implementation in SWAN is out of the scope of this paper.

This study aims at applying the WBLM source functions of Du et al. (2017) in SWAN for real wave simulations. Several improvements on the WBLM wind-input and white-capping dissipation source functions are realized. Firstly, the WBLM wind-input source function is modified by considering the wind profile change in the estimation of the non-dimensional critical height. Secondly, a revised white-capping dissipation source function is applied, which enables the WBLM method to be used for varying wind conditions. Thirdly, a few refinements of the numerical algorithms of WBLM in SWAN are done to improve the model stability and efficiency, which make it possible to be used for large-domain and high-resolution simulations.

The new pair of WBLM wind-input and dissipation source functions is calibrated with fetch-limited and depth-limited simulations. It is proven to be able to reproduce the benchmark wave growth curve of Kahma and Calkoen (1992), the energy level, and the one-dimensional wave spectrum measured by Young and Babanin (2006b) in the depth-limited study.

The WBLM wind-input and dissipation source functions are validated with several point measurements during two storms over the North Sea. Results show that, in comparison to the original wind-input and dissipation source functions in SWAN, namely Komen et al. (1984) and Janssen (1991), WBLM improves the prediction of significant wave height and mean wave period in comparison to measurements.

The source code for SWAN used in this study is freely available at http://swanmodel.sourceforge.net (last access: 21 June 2017). The bathymetry data is obtained from EMODnet (http://www.emodnet-bathymetry.eu/, last access: 20 November 2014). The observational wave data is downloaded from NOOS (https://noos.bsh.de/, last access: 15 June 2017), FINO (http://fino.bsh.de, registration needed, last access: 3 April 2018), and eKlima (http://sharki.oslo.dnmi.no, registration needed, last access: 17 November 2016). CFSv2 10 m wind speed is download from NCEP Climate Forecast System Version 2 (CFSv2) Selected Hourly Time-Series Products (Saha et al., 2011). The model data and source code modifications can be obtained from the corresponding author.

The D85 (Donelan et al., 1985) spectra are described by

where f is the frequency and fp is the frequency at the spectral peak. αD is a equilibrium range parameter which is written as

where U10 is 10 m wind speed. cp is the phase velocity at the spectral peak. In deep water conditions, , where g is the gravity acceleration. γD is a peak enhancement factor:

and σD is a peak width parameter, which is written as

The JONSWAP (Hasselmann et al., 1973) spectra are described by

where the equilibrium range parameter is written as

where () is a non-dimensional fetch, and x is the fetch. Parameterization for the peak enhancement factor (γJ) for JONSWAP spectra is not provided by Hasselmann et al. (1973). According to Hasselmann et al. (1973), γJ is scatted between 1.5 and 6.0, with an average value of 3.3. So, we use the same equation as D85 (Eq. A2) with a limit of . The peak width parameter is written as

For both D85 and JONSWAP spectra, the peak frequency (fp) for a given wind speed (U10) and fetch (x) is calculated from the fetch-limited wave growth relationship of Kahma and Calkoen (1992):

Taking X as the observation value and Y as the modeled value, the mean difference is defined as

The root mean square error is defined as

The scatter index is defined as

The updated WBLM model was developed by JD. JD, RB, and XGL designed all the numerical experiments, which where performed by JD. RB provided the measurement data of RUNE. The manuscript was written by JD with the assistance of RB, XGL, and MK. All authors worked on the paper.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This article is part of the special issue “Coastal modelling and uncertainties based on CMEMS products”. It is not associated with a conference.

This project has received funding from the Danish Forskel project X-WiWa (PSO-12020), the

EU CEASELESS project (H2020-EO2016-730030), and the National Key Research and Development

Program of China (2017YFC1404200). We are grateful to Jean Raymond Bidlot from ECMWF,

Anna Rutgersson from Uppsala University, and Henrik Bredmose from DTU Wind Energy for

helpful discussions and inputs. Furthermore, we would like to thank Rogier Floors from

DTU Wind Energy for providing the measurement data during Danish ForskEL project RUNE

(12263).

Edited by: Manuel Espino Infantes

Reviewed by: one anonymous referee

Alves, J. H. G. M. and Banner, M. L.: Performance of a Saturation-Based Dissipation-Rate Source Term in Modeling the Fetch-Limited Evolution of Wind Waves, J. Phys. Oceanogr., 33, 1274–1298, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0485(2003)033<1274:POASDS>2.0.CO;2, 2003. a

Ardhuin, F.: Dissipation parameterizations in spectral wave models and general suggestions for improving on today's wave models Fabrice Ardhuine, in: ECMWF Workshop on Ocean Waves, June, 113–124, 2012. a, b

Ardhuin, F. and Roland, A.: Coastal wave reflection, directional spread, and seismoacoustic noise sources, J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans, 117, 1–16, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011JC007832, 2012. a

Ardhuin, F., Rogers, E., Babanin, A. V., Filipot, J.-F., Magne, R., Roland, A., van der Westhuysen, A., Queffeulou, P., Lefevre, J.-M., Aouf, L., and Collard, F.: Semiempirical Dissipation Source Functions for Ocean Waves, Part I: Definition, Calibration, and Validation, J. Phys. Oceanogr., 40, 1917–1941, https://doi.org/10.1175/2010JPO4324.1, 2010. a, b, c, d, e

Ardhuin, F., Roland, A., Dumas, F., Bennis, A.-C., Sentchev, A., Forget, P., Wolf, J., Girard, F., Osuna, P., and Benoit, M.: Numerical wave modelling in conditions with strong currents: dissipation, refraction and relative wind, J. Phys. Oceanogr., 42, https://doi.org/10.1175/JPO-D-11-0220.1, 2012. a

Babanin, A. V. and Young, I. R.: Two-phase behaviour of the spectral dissipation of wind waves, in: Proc. Ocean Waves Measurements and Analysis, Fifth Intern, Symposium WAVES2005, December 2016, 2005. a

Babanin, A. V., Tsagareli, K. N., Young, I. R., and Walker, D. J.: Numerical Investigation of Spectral Evolution of Wind Waves, Part II: Dissipation Term and Evolution Tests, J. Phys. Oceanogr., 40, 667–683, https://doi.org/10.1175/2009JPO4370.1, 2010. a, b

Banner, M. L. and Morison, R. P.: Refined source terms in wind wave models with explicit wave breaking prediction, Part I: Model framework and validation against field data, Ocean Model., 33, 177–189, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocemod.2010.01.002, 2010. a

Battjes, J. A. and Janssen, J. P. F. M.: Energy loss and set-up due to breaking of random waves, in: Proceedings of 16th International Conference on Coast. Eng., New York, American Society of Civil Engineers, 569–587, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004, 1978. a, b

Bidlot, J.-R.: Present Status of Wave Forecasting at ECMWF, in: ECMWF Workshop on Ocean Waves, Shinfield Park, Reading RG2 9AX, United Kingdom, 25–27 June 2012, 2012. a, b, c

Bidlot, J.-R., Janssen, P. A. E. M., and Abdalla, S.: A revised formulation of ocean wave dissipation and its model impact, ECMWF Technical Memorandum, 509, http://www.citeulike.org/group/11419/article/6354018 (last access: 14 October 2014), 2007. a, b, c, d, e

Bolaños, R.: D3.3 Metocean Conditions and Wave Modelling, Tech. Rep. November, available at: http://orbit.dtu.dk/files/155595377/D3p3_final.pdf (last access: 10 April 2017), 2016. a

Bolaños, R. and Rørbæk, K.: D3.1 Metocean Buoy Deployment, Tech. Rep. November, available at: http://orbit.dtu.dk/files/155595376/D3p1_final.pdf, (last access: 10 April 2017), 2016. a

Bolaños, R., Larsén, X. G., Petersen, O., Nielsen, J., Kelly, M., Kofoed-Hansen, H., Du, J., Sørensen, O., Larsen, S., Hahmann, A., and Badger, M.: Coupling atmospherere and waves for coastal wind turbine design, Proceedings of the Coast. Eng. Conference, 1–11 January 2014, 2014. a

Booij, N., Ris, R., and Holthuijsen, L.: A third-generation wave model for coastal regions, I-Model description and validation, J. Geophys. Res., 104, 7649–7666, https://doi.org/10.1029/98JC02622, 1999. a, b

Cavaleri, L.: Wave Modeling-Missing the Peaks, J. Phys. Oceanogr., 39, 2757–2778, https://doi.org/10.1175/2009JPO4067.1, 2009. a

Cavaleri, L., Alves, J. H. G. M., Ardhuin, F., Babanin, A., Banner, M., Belibassakis, K., Benoit, M., Donelan, M., Groeneweg, J., Herbers, T. H. C., Hwang, P., Janssen, P. A. E. M., Janssen, T., Lavrenov, I. V., Magne, R., Monbaliu, J., Onorato, M., Polnikov, V., Resio, D., Rogers, W. E., Sheremet, A., McKee Smith, J., Tolman, H. L., van Vledder, G., Wolf, J., and Young, I.: Wave modelling – The state of the art, Prog. Oceanogr., 75, 603–674, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pocean.2007.05.005, 2007. a

Donelan, M. A., Hamilton, J., and Hui, W. H.: Directional Spectra of Wind-Generated Waves, Philos. T. R. Soc. Lond., 315, 509–562, https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.1985.0054, 1985. a, b, c

Du, J.: Coupling atmospheric and ocean wave models for storm simulation, Ph.D. thesis, Technical University of Denmark, https://doi.org/10.11581/DTU:00000020, 136 pp., 2017. a, b

Du, J., Bolaños, R., and Larsén, X.: The use of a wave boundary layer model in SWAN, J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans, 122, 42–62, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016JC012104, 2017. a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, j, k, l, m, n, o, p, q, r, s

Floors, R., Hahmann, A., Peña, A., and Karagali, I.: Estimating near-shore wind resources E-Report DTU Wind Energy, Vol. 0116, available at: http://orbit.dtu.dk/files/126992882/final.pdf (last access: 10 April 2017), 2016a. a

Floors, R., Lea, G., Peña, A., Karagali, I., and Ahsbahs, T.: Report on RUNE's coastal experiment and first inter-comparisons between measurements systems, Vol. 0115, available at: http://orbit.dtu.dk/files/127277148/final.pdf (last access: 10 April 2017), 2016b. a, b

Floors, R., Peña, A., Lea, G., Vasiljevic, N., Simon, E., and Courtney, M.: The RUNE experiment-A database of remote-sensing observations of near-shore winds, Remote Sens., 8, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs8110884, 2016c. a

Hasselmann, K.: On the spectral dissipation of ocean waves due to white capping, Bound-Lay. Meteorol., 6, 107–127, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00232479, 1974. a

Hasselmann, K., Barnett, T. P., Bouws, E., Carlson, H., Cartwright, D. E., Enke, K., Ewing, J. A., Gienapp, H., Hasselmann, D. E., Kruseman, P., Meerburg, A., Muller, P., Olbers, D. J., Richter, K., Sell, W., and Walden, H.: Measurements of Wind-Wave Growth and Swell Decay during the Joint North Sea Wave Project (JONSWAP), Ergänzungsheft zur Deutschen Hydrographischen Zeitschrift Reihe, A8, p. 95, 2710264, 1973. a, b, c, d, e, f, g

Hua, F. and Yuan, Y.: Theoretical Study of Breaking Wave Spectrum and its Application, in: Breaking Waves, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 277–282, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-84847-6-30, 1992. a

Janssen, P. A. E. M.: Quasi-linear Theory of Wind-Wave Generation Applied to Wave Forecasting, J. Phys. Oceanogr., 21, 1631–1642, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0485(1991)021<1631:QLTOWW>2.0.CO;2, 1991. a, b, c, d, e, f

Kahma, K. K. and Calkoen, C. J.: Reconciling Discrepancies in the Observed Growth of Wind-generated Waves, 22, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0485(1992)022<1389:RDITOG>2.0.CO;2, 1992. a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, j

Komen, G. J., Hasselmann, S., and Hasselmann, K.: On the Existence of a Fully Developed Wind-Sea Spectrum, J. Phys. Oceanogr., 14, 1271–1285, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0485(1984)014<1271:OTEOAF>2.0.CO;2, 1984. a, b, c, d, e, f, g

Komen, G. J., Cavareli, L., Donelan, M., Hasselmann, K., Hasselmann, S., and Janssen, P. A. E. M.: Dynamics and modelling of ocean waves, Cambridge University Press, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511628955, 532 pp., 1994. a, b, c, d

Larsén, X. G., Du, J., Bolaños, R., and Larsen, S.: On the impact of wind on the development of wave field during storm Britta, Ocean Dynam., 67, 1407–1427, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10236-017-1100-1, 2017. a, b

Leckler, F., Ardhuin, F., Filipot, J. F., and Mironov, A.: Dissipation source terms and whitecap statistics, Ocean Model., 70, 62–74, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocemod.2013.03.007, 2013. a

Longuet-Higgins, M. S.: On Wave Breaking and the Equilibrium Spectrum of Wind-Generated Waves, P. Roy. Soc. A-Math. Phy., 310, 151–159, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.1969.0069, 1969. a

Melville, W. K. and Matusov, P.: Distribution of breaking waves at the ocean surface., Nature, 417, 58–63, https://doi.org/10.1038/417058a, 2002. a

Miles, J. W.: On the generation of surface waves by shear flows, Part 2, J. Fluid Mech., 3, 568–582, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022112059000830, 1957. a, b, c

Phillips, O. M.: Spectral and statistical properties of the equilibrium range in wind-generated gravity waves, J. Fluid Mech., 156, 505–531, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022112085002221, 1985. a, b, c

Polnikov, V. G.: On a description of a wind-wave energy dissipation function, in: The Air-Sea Interface: Radio and Acoustic Sensing, Turbulence and Wave Dynamics, edited by: Donelan, M. A., Hui, W. H., and Plant, W. J., Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, University of Miami, 277–282, 1993. a

Saha, S., Moorthi, S., Wu, X., Wang, J., Nadiga, S., Tripp, P., Behringer, D., Hou, Y., Chuang, H., Iredell, M., Ek, M., Meng, J., Yang, R., Mendez, M. P., van den Dool, H., Zhang, Q., Wang, W., Chen, M., and Becker, E.: NCEP Climate Forecast System Version 2 (CFSv2) Selected Hourly Time-Series Products. Research Data Archive at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, Computational and Information Systems Laboratory, updated monthly, https://doi.org/10.5065/D6N877VB, last access: 17 November 2016, 2011. a

Snyder, R. L., Dobson, F. W., Elliott, J. A., and Long, R. B.: Array measurements of atmospheric pressure fluctuations above surface gravity waves, J. Fluid Mech., 102, 1–59, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022112081002528, 1981. a, b

Sørensen, O. R., Kofoed-Hansen, H., Rugbjerg, M., and Sørensen, L. S.: A third-generation spectral wave model using an unstructured finite volume technique, Proceedings of the 29th Intern. Conf. on Coastal Eng., 1, 894–906, https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812701916-0071, 2005. a

SWAN: Swan Scientific and Technical Documentation, SWAN Cycle III, Version 41.01, 1–132, 2014. a

Tolman, H. L. and Chalikov, D.: Source Terms in a Third-Generation Wind Wave Model, 26, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0485(1996)026<2497:STIATG>2.0.CO;2, 1996. a

van der Westhuysen, A. J., Zijlema, M., and Battjes, J. A.: Nonlinear saturation-based whitecapping dissipation in SWAN for deep and shallow water, Coast. Eng., 54, 151–170, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coastaleng.2006.08.006, 2007. a, b

Young, I. R. and Babanin, A. V.: Spectral Distribution of Energy Dissipation of Wind-Generated Waves due to Dominant Wave Breaking, J. Phys. Oceanogr., 36, 376–394, https://doi.org/10.1175/JPO2859.1, 2006a. a, b

Young, I. R. and Babanin, A. V.: The form of the asymptotic depth-limited wind wave frequency spectrum, J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans, 111, 1–15, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005JC003398, 2006b. a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i

Young, I. R., Banner, M. L., Donelan, M. A., Babanin, A. V., Melville, W. K., Veron, F., and McCormick, C.: An integrated system for the study of wind-wave source terms in finite-depth water, J. Atmos. Ocean. Tech., 22, 814–831, https://doi.org/10.1175/JTECH1726.1, 2005. a

Yuan, Y., Tung, C. C., and Huang, N. E.: Statistical Characteristics of Breaking Waves, in: Wave Dynamics and Radio Probing of the Ocean Surface, Springer US, Boston, MA, 265–272, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4684-8980-4-18, 1986. a

Zieger, S., Babanin, A. V., Erick Rogers, W., and Young, I. R.: Observation-based source terms in the third-generation wave model WAVEWATCH, Ocean Model., 96, 2–25, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocemod.2015.07.014, 2015. a

Zijlema, M., Van Vledder, G. P., and Holthuijsen, L. H.: Bottom friction and wind drag for wave models, Coast. Eng., 65, 19–26, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coastaleng.2012.03.002, 2012. a, b