the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Seasonal variability of intermediate water masses in the Gulf of Cádiz: implications of the Antarctic and subarctic seesaw

Ivan Parras-Berrocal

Miguel Bruno

Ricardo Sánchez-Leal

Francisco Javier Hernández-Molina

Global circulation of intermediate water masses has been extensively studied; however, its regional and local circulation along continental margins and variability and implications on sea floor morphologies are still not well known. In this study the intermediate water mass variability in the Gulf of Cádiz (GoC) and adjacent areas has been analysed and its implications discussed. Remarkable seasonal variations of the Antarctic Intermediate Water (AAIW) and the Subarctic Intermediate Water (SAIW) are determined. During autumn a greater presence of the AAIW seems to be related to a reduction in the presence of SAIW and Eastern North Atlantic Central Water (ENACW). This interaction also affects the Mediterranean Water (MW), which is pushed by the AAIW toward the upper continental slope. In the rest of the seasons, the SAIW is the predominant water mass reducing the presence of the AAIW. This seasonal variability for the predominance of these intermediate water masses is explained in terms of the concatenation of several wind-driven processes acting during the different seasons. Our finding is important for a better understanding of regional intermediate water mass variability with implications in the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), but further research is needed in order to decode their changes during the geological past and their role, especially related to the AAIW, in controlling both the morphology and the sedimentation along the continental slopes.

- Article

(9995 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(809 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

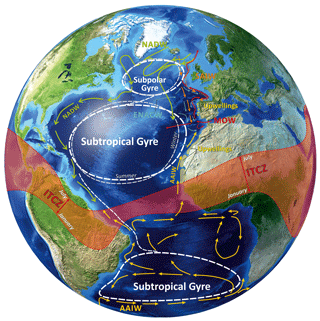

The intermediate water masses, their circulation and associated oceanographic processes are essential to understanding global Thermohaline Circulation (THC). Concretely, these water masses take part of the Meridional Overturning Circulation (MOC), carrying a significant part of the meridional heat, freshwater and nutrient transport in the global ocean. Also, it is an important oceanic sink for anthropogenic CO2 (Sabine et al., 2004). In Fig. 1 a general sketch of the main circulation patterns that these intermediate water masses demonstrate in the Atlantic Ocean is shown.

Figure 1Sketch of the intermediate water circulation in the Atlantic Ocean. The position of the main gyres, the Intertropical Confluence Zone (ITCZ) and circulation of the AAIW, SAIW, ENACW and MW w< are indicated. Compilation is based on Krauss et al. (1987), Stramma and Siedler (1988), Faugères et al. (1993), Iorga and Lozier (1999), Pickart et al. (1999), Stramma and England (1999), Coulbourne and Foote (2000), Lavander et al. (2000), Rhein (2000), Fratantoni (2001), Raymo et al. (2004), Mackie (2005), Peliz et al. (2005, 2009), Rahmstorf (2007), Stein (2007), Gil et al. (2008), Yashayaev and Clarke (2008), Hernández-Molina et al. (2011) and references therein, Cheng et al. (2012) and Pérez et al. (2013).

Although their circulation at global scale has been extensively studied (Rahmstorf, 2007), the spreading, interactions and the regional implications of these intermediate waters along continental margins are still not well known. At a global scale, the Antarctic Intermediate Water (AAIW) is one of the most relevant intermediate waters, since it is an important component of the upper branch of the MOC in the Southern Hemisphere subtropical gyre (Pahnke et al., 2008; Talley, 2003). It is characterized by a salinity minimum and high nutrient concentration between 500 and 800 m to ca. 1500 m depth (Tsuchiya et al., 1992), with its main core located at 900 m (Fig. 2). The AAIW spreads along the eastern boundaries of all major oceans, although its original characteristics are best observed in the Southern Hemisphere (Stramma and England, 1999).

Several authors have reported a significant time variability of the AAIW presence in the North Atlantic between glacial and interglacial periods (Oppo, 2000; Curry and Oppo, 2005; Jung et al., 2010; Makou et al., 2010; Curry, 2010; Muratli et al., 2010; Wainer et al., 2012). The AAIW is well identified year-round in the eastern boundary of the North Atlantic. It spreads along the African coastline up to approximately 28.5∘ N, but during autumn it can extend up to 32∘ N (Tsuchiya et al., 1992; Machín and Pelegrí, 2009) and even into the Gulf of Cádiz (GoC) (Cabeçadas et al., 2002; Louarn and Morin, 2011; Hernández-Molina et al., 2014), where it interacts with the Mediterranean Water (MW), perhaps restricting the spreading of the latter, especially between summer and winter (Cabeçadas et al., 2002; Knoll et al., 2002; Louarn and Morin, 2011).

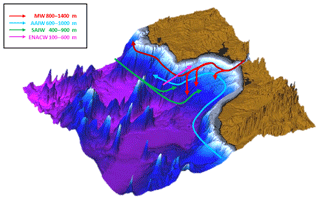

Figure 2Illustration of intermediate water mass circulation in the GoC. The red line indicates the MW along the Spanish and Portuguese coast. The blue line is for the AAIW coming from the African coast from the south. The green line is for the modified SAIW coming from the northwest of the Iberian Peninsula. The purple line is for the ENACW coming from the western part of the GoC.

Traditionally, only two intermediate water masses are considered in the GoC (Ambar and Howe, 1979a; Baringer and Price, 1997; Van Aken, 2000): the Eastern North Atlantic Central Water (ENACW) and the Mediterranean Water (MW) (Fig. 2). The ENACW is formed by strong evaporation first and further winter cooling later along the Azores Front (Pollard and Pu, 1985; Rios et al., 1992). From here, it circulates southward penetrating into the GoC in the 250–700 m depth range. Here, the ENACW interacts actively with the MW close to the western side of the Strait of Gibraltar (Louarn and Morin, 2011) and with the upper MW core (Ambar and Howe, 1979b) further west, throughout the GoC continental slope (Louarn and Morin, 2011; Bellanco and Sánchez-Leal, 2016).

Another important intermediate water mass in the GoC is the Subarctic Intermediate Water (SAIW). It is formed by winter cooling of surface water in three main regions: (a) north-western North Atlantic, north of the subarctic front, (b) the Porcupine Seabight, and (c) northern Bay of Biscay (Van Aken, 2001). A significant part of the variety of water formed in the latter two regions progresses below the North Atlantic Current and flows towards the Eastern Atlantic margin, penetrating into the GoC from a south-southwestern direction and moving in the depth range of 400–800 m (Cabeçadas et al., 2002).

In several articles, the SAIW and the ENACW have been referred to as the lower and upper ENACW (Louarn and Morin, 2011; Carracedo et al., 2014) or as subpolar and subtropical origin ENACW (Voelker et al., 2015). Following Van Aken (2000, 2001) we use the former denominations. Currently, there is a lack of information about the seasonal variability of these intermediate water masses in the region. Bellanco and Sánchez-Leal (2016) analysed the interaction between the upper MW core and the ENACW on the upper GoC continental slope. The authors suggested an enhanced upper MW core and a less stratified ENACW in winter, resulting in an upslope expansion of the MW core and a more effective mixing with the overlaying ENACW. In contrast, they noted a weakened and deeper MW core and a thicker ENACW during late summer and early autumn.

The study by Machín and Pelegrí (2009) is relevant for consideration of the seasonal variations of the AAIW water within the GoC. Although focussed on the Canary Islands region, the authors reported a clear AAIW increase during autumn when compared with other seasons. The question of whether this AAIW increase has implications on the other water masses circulating in the region is addressed in the present paper. Therefore, our main aims are as follows: (a) to determine the AAIW extension and variability in the vicinity of the GoC; (b) to identify its interplays with other intermediate water masses; and (c) to hypothesize about its implication on the continental margin morphology. We analyse a large conductivity, temperature, and depth (CTD) and oxygen concentration profile database extracted from various providers, complemented by the World Ocean Atlas (WOA13).

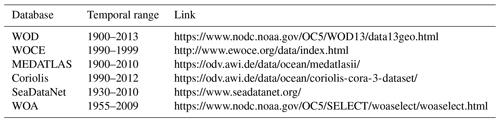

2.1 Dataset

In order to identify water masses coming from remote locations we considered a study area spanning from 30–40∘ N to 15–5.5∘ W (Fig. 3). The domain includes the GoC and the surrounding areas into the GoC (African coast, Portuguese coast and Strait of Gibraltar). We have gathered all available observations from WODB, WOCE, MEDATLAS, Coriolis and SeaDataNet databases (Table 1), complemented by data from other individual cruises, carried out by the University of Cádiz (Golfo, 2001; Medout, 2011; Estrecho, 2008). The temporal distribution of profiles span from 1900 to 2013, although the bulk of the data was acquired after 1950. The resulting product consists of a database including vertical profiles of temperature, salinity, density and dissolved oxygen concentration. The latter will be used to discern the AAIW from the SAIW and the ENACW Machín and Pelegrí, 2009; Louarn and Morin, 2011; Carracedo et al., 2014; Hernández-Molina et al., 2014). We also included the World Oceanographic Atlas monthly objectively analysed (1∘ grid) climatological fields (https://www.nodc.noaa.gov/OC5/woa13/, last access: October 2018).

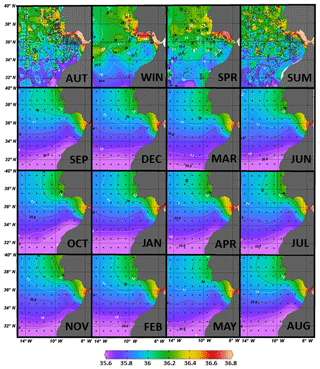

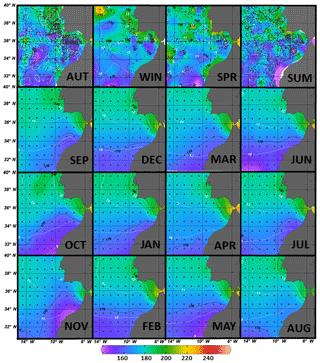

Figure 3Observed salinity on the isopycnic surface σ=27.5 for the different seasons (top row). The rows below show the same distributions for each climatological month as shown by WOA data. The white lines represent the temperature values at density σ=27.5.

To study the seasonal variability, we grouped observations into 3-month seasonal bins, starting in December (i.e. winter spans December through February, spring spans March through April, and so on). Since the analysis will be focussed on intermediate water masses, we only used the observations taken within the 400–1000 m depth range. Figures 3 and 4 show the seasonal distribution of vertical profiles as well as the WOA data nodes. The figures reveal the homogeneous spatial distribution of profiles.

In addition, to examine the possible mechanisms behind the time variability of water masses we used monthly wind data taken from the ERA-Interim reanalysis (Dee et al., 2011) spanning 1979–2018, downloaded from https://www.ecmwf.int/en/forecasts/datasets/archive-datasets/browse-reanalysis-datasets(last access: October 2018). The spatial data resolution is . These monthly wind data will be analysed in combination with the monthly WOA data.

2.2 Optimum multiparameter analysis

In order to quantify the percentage in which each water mass was presented in the studied area, we applied the optimum multiparameter analysis (OMP) to each seasonal dataset. This technique assumes that the value of any seawater property, measured at each depth in the ocean, is the result of the mixing of a certain number of water masses present in the region (Tomczak and Large 1989). It has become a standard tool in oceanography to resolve water mass mixing in regional-scale studies (Poole and Tomczak, 1999; Álvarez et al., 2004; Johnson, 2008; Louarn and Morin, 2011; Pardo et al., 2012).

Mathematically, it implies solving an overdetermined system of linear equations which is composed of (n+1) equations, “n” being the number of unknown variables, the fraction (percentage) of each water mass present in the mixing. As an example, for a problem with four water masses the following system of equations would apply:

where the xi's are the fraction (percentage) of each water mass present (subscript i takes the values 1, 2, 3, 4); To, So and Co, the observed temperature, salinity and concentration of some conservative property (i.e. oxygen) at each point; Tis, Sis and Cis are the characteristic values of properties for each water mass type.

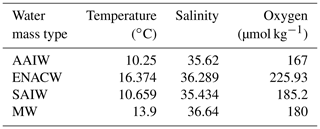

The analysis is restricted to the depth range of 400–1000 m and considers the following four water mass types: AAIW, SAIW, ENACW and MW; the resulting percentages are binned into nine boxes with a resolution of (see Fig. 6). The characteristic values of properties for these water masses in the GoC region have been taken from Louarn and Morin (2011; Table 2). Note that the difference in S and T between the AAIW and SAIW is very small and can only be distinguished by their oxygen concentration. For this reason, we have chosen oxygen as the other conservative property in the OMP analysis.

2.3 Principal component analysis

Principal component analysis (PCA) is a statistical procedure that allows the transformation of a set of observations, which contain variables possibly correlated among them, into a set of values of uncorrelated variables called principal components (Pearson, 1901). When the problem under study contains a large number of observations, the maximum number of principal components to be sought for is equal to the number of variables. This transformation is defined in such a way that the first principal component has the largest possible variance, and the successive components progressively reduce their variance.

This technique has been applied using the MATLAB function PCA on the fractions of the four water mass types determined in the OMP analysis previously described, in order to identify common patterns of behaviour among them while they change with the seasons. Therefore, the variables of our PCA problem are these fractions of each water mass type (AAIW, ENACW, SAIW, MW) at each of the nine boxes shown in Fig. 6. Note that there are 36 variables (4 in each box) in the performed PCA. Subsequently, the values of these variables, through the different seasons, are arranged into four rows, and the resulting file is subjected to the PCA. The resulting principal components (PCs) may be expressed as follows:

where t stands for the time (season); indexes k and i stand for the given PC and variables respectively, with nv being the number of analysed variables (36 in our case); is the average value of the given variables through the different seasons. In this way, each PC is built as a linear combination of the observed variables xi weighted by a set of coefficients . At the same time, matrix algebra allows us to write the inverse problem:

where nc is the number of considered PCs. Therefore, each of the observed values of the variables xi may be expressed as a linear combination of the resolved PCs weighted by the coefficients already introduced.

Now the absolute values that take these coefficients for a given PC along the different variables enable us to identify which of them are related to that PC. In order to visualize the temporal patterns contained in the resolved PCs, it is worthwhile to separate the products (PCk) corresponding to each climatic season for each PC. Note that the values of these products represent deviations of the variables with respect to their time-averaged values, as Eq. (6) indicates. Later, using these quantities, we will be able to map the seasonal variability contained in each PC and assess how intense its manifestation in the different spatial locations of the studied area is.

3.1 Spatial distribution of physical–chemical properties

As a first step of the data analysis, several spatial representations of the different variables have been elaborated on:

- a.

representation of the spatial distribution of the variables on the isopycnic surface of 27.5, which best characterizes the position of the AAIW core in the region (Van Aken, 2001; Cabeçadas et al., 2002; Louarn and Morin, 2011; Hernández-Molina et al., 2014);

- b.

representation of vertical sections of the variables along the meridional section at 36∘ N, which meets two important conditions: (i) an adequate identification of the AAIW pathway by the GoC and (ii) a high number of profiles covering as homogeneously as possible, during the different seasons, the given vertical sections.

3.1.1 Spatial distribution on the 27.5 isopycnic surface

Figures 3 and 4 show, respectively, the distributions of salinity and oxygen concentration on the 27.5 isopycnic surface, for the seasonal values contained in the observed data (upper row) and for the monthly values provided by the WOA database (following three rows).

Concerning the observed data, we found low oxygen concentration values (Fig. 4) coincident with low salinity values (Fig. 3), attributable to the AAIW presence (see Table 2), penetrating from lower latitudes into the GoC in all seasons, although it is remarkable that this penetration is more accentuated and closer to the African coast in autumn but also in summer. Note also that the lowest presence of AAIW is found in spring (Figs. 3 and 4).

Figure 4Observed oxygen concentration on the isopycnic surface σ=27.5 for the different seasons (top row). The rows below show the same distributions for each climatological month as shown by WOA data. The white lines represent the temperature values at density σ=27.5.

The monthly distributions shown by the WOA data on the 27.5 isopycnic surface roughly agree with the previous commented behaviour. It must be noted that in this case these data do not offer such a detailed spatial resolution of the region closer to the continental margin as the observed data do. However, those maps allow us to gain insight into the intra-annual variability of the AAIW distribution close to the GoC. In this sense, attending to the oxygen concentration distribution, which offers the most marked differences with the other water masses (see Table 2), we can see that the major entrance of the AAIW close to the African coast occurs in November. At the same time, we can see that the spreading of the AAIW toward the GoC is more restricted during the spring months, only slightly suggested in March by the salinity distribution and in April by the oxygen distribution. In addition, in May, June and July this spreading is re-established, albeit to a lesser extent than in autumn.

3.1.2 Vertical section distribution in zonal direction at 36∘ N

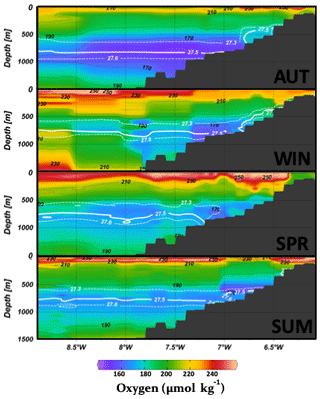

Figure 5 shows the zonal distribution of dissolved oxygen, salinity and temperature along 36∘ N. Low oxygen values characteristic of the AAIW occur year-long in the 700–1200 m depth range. As suggested before, the lowest oxygen concentrations occur in autumn close to the African continental slope. This increased AAIW presence close to the African coast in autumn has already been reported (Tsuchiya et al., 1992; Knoll et al., 2002; Machín and Pelegrí, 2009, 2016), although at lower latitudes.

Figure 5Vertical oxygen concentration sections disposed zonally at 36∘ N of observed variables for each season.

In summer, the low-oxygen zone spreads zonally, extending to Cape St. Vicente (Fig. 5). In winter, the low oxygen signal is less evident and relative oxygen values are higher, perhaps suggesting weaker AAIW presence in winter. Note that salinity and temperature distributions are not helpful to discern between AAIW and SAIW (see Table 2).

3.2 OMP analysis

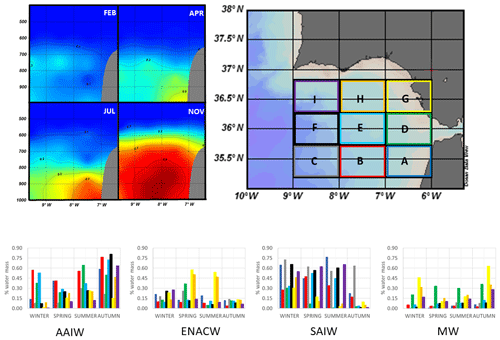

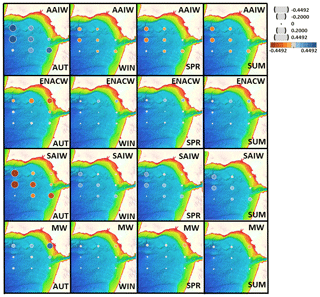

The AAIW is present as an intermediate water mass extending along the middle slope from northern Morocco to the GoC year-round. There is a certain intra-annual variability, with enhanced AAIW presence in autumn. To elucidate the pattern, we applied the OMP analysis to the dataset of vertical profiles in the target depth range (400–1000 m). Subsequently, we binned the results into nine boxes (Fig. 6). As suggested before, the highest AAIW percentages are found in autumn. Only boxes G (the closest to the continent) and C (the farthest from the coast) always show AAIW percentages below 40 %. The SAIW shows its lower percentages (less than 10 %) in boxes closer to the Iberian coast (from E to I) during autumn, while the higher values are found in winter in these boxes. The ENACW in the closer coast boxes (G and H) shows its higher values in spring and summer, while the MW shows these in winter and autumn. These results show the relationship among the different water masses. On the one hand, in autumn the AAIW displaces the SAIW, while the reverse situation occurs in winter. On the other hand, the alternation in predominance of these two water masses seems to be related to (i) a major confinement of the MW toward the coast in autumn (by the enhanced AAIW presence) and winter (by the SAIW) and (ii) a displacement toward offshore of the ENACW in the same seasons.

Figure 6Values of percentages of each water mass resulting from the OMP analysis in each of the boxes shown in the map in the bottom right-hand corner, for each season. In the bottom left-hand corner, the resulting percentages are shown from the OMP analysis applied on the WOA database for a zonal section at 36∘ N in selected climatological months. The data selected for OMP analysis are those in the depth range of 400–1000 m.

Regarding the OMP analysis on the WOA data, we have selected data located around a zonal section at 36∘ N (Fig. 6) in order to ensure a clear identification of the AAIW coming from the Canary Islands latitude where this water mass has been previously identified close to the African coast (Machín and Pelegrí, 2009, 2016; Louarn and Morin, 2011). Similar to the case of the observed profiles only data in the depth range of 400–1000 m have been considered. The water mass percentages have been computed for each month along the climatic year. Figure 6 shows the vertical sections of computed percentages of AAIW for February, April, July and November. The stronger AAIW presence occurs in November, when it is found near the African continent. We observe a weaker AAIW presence from February to April. The OMP results indicates that the autumn increase of the AAIW goes along with a reduction of the SAIW fraction, hence illustrating a sort of competitive seesaw between the two water masses. Figure 10a shows the climatic monthly values of the averaged percentages over the vertical section percentages of the four water masses. It can be seen that the SAIW is the most predominant water throughout most of the year, namely greater than 70 % for all months, with the exception of November when the AAIW rises to 40 %.

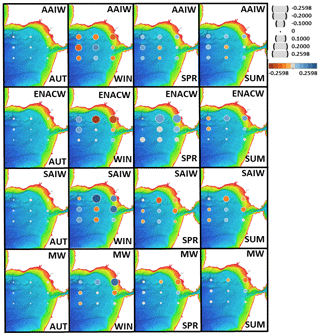

3.3 PCA

In order to carry out a better assessment of the seasonal variations of water mass percentages and the interrelation between the different water masses, we have applied a PC on the set of computed percentages. As explained in Sect. 2, this technique will allow us to identify common patterns in the seasonal variations of these percentages in the nine boxes located in the GoC shown in Fig. 6.

In Figs. 7 and 8, the results of this analysis are shown. The first PC (Fig. 7) shows a clear interaction between the AAIW and SAIW. In autumn a greater presence of the AAIW, coming from lower latitudes, seems to be related to a reduction in the presence of the SAIW coming from higher latitudes. In addition, this first principal component also reflects a significant increase in the presence of the MW in the box closest to the continental slope. The second PC (Fig. 8) picks up another clear interaction between the four water masses, but now it seems to be caused by a greater presence of the SAIW in winter that produces a displacement of the AAIW and ENACW and again a confinement of the MW against the continental slope.

Figure 7Seasonal variation of the percentages of each water mass given by the first principal component resulting from the PCA on the percentages previously estimated in the nine boxes considered in the GoC. Values are deviations from the averaged, through the different seasons, percentage at each location.

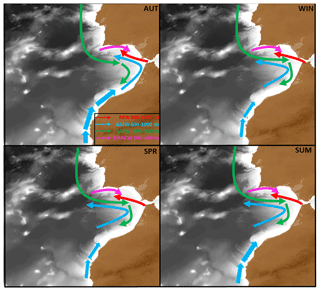

The interpretation of these results is sketched in Fig. 9, which shows the likely preferential tracks of the different intermediate waters along the GoC in the different seasons. In autumn the AAIW penetrates closer to the continental slope while the SAIW runs more displaced southward. Also, the ENACW and MW are found near the coast. In winter the situation is reversed regarding AAIW and SAIW behaviour. Now the SAIW is flowing closest to the continental slope, the AAIW is displaced southward and once again the ENACW and MW are confined toward the continental slope. The situation in spring and summer is similar to the one in winter, although in summer an increase in the transport of AAIW, close to the African coast, is observed.

3.4 Wind forcing in the North Atlantic and intermediate water presence in the GoC

Variability of the meridional transport in the North Atlantic is linked to two important wind-driven mechanisms (Machín and Pelegrí, 2009; Barrier et al., 2014): the meridional Sverdrup transport and the Ekman pumping.

The meridional Sverdrup transport is calculated as follows:

and the Ekman pumping as

where τx and τy are, respectively, the zonal and meridional components of wind stress; ρ0 is seawater density; is the Coriolis parameter, where β0 is the variation with latitude of f in the β plane.

We computed both magnitudes from wind velocity data provided by ERA-Interim reanalysis spanning the period 1979–2018.

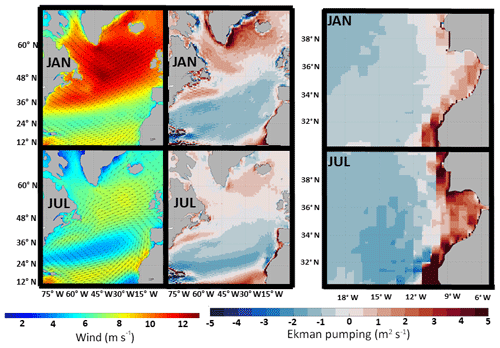

Figures 11 and 12 show, respectively, the meridional Sverdrup transport and the Ekman pumping for January and July, the two seasonal opposites in a climatological year. They are shown for the region of the North Atlantic spanning 10 to 70∘ N and for the zoomed region focussed on the GoC.

The meridional Sverdrup transport peaks close to the eastern coast (Fig. 11). This suggests small-scale horizontal wind stress gradients near the continent. The Sverdrup transport along the eastern coast of Portugal is southward year-round, with the highest (lowest) values in January (July). Along the African coast this transport is northward year-round, with the highest (lowest) values in July (January). More detailed information about the seasonal variations of these transports can be found in Fig. 10b, where the mean monthly climatological values of Sverdrup transport are shown at three points close to the coast, namely at 30, 35.5 and 40∘ N. At 30∘ N meridional transport is positive (northward) all year showing an increase in summer with a peak in July. This northward transport close to the African coast may contribute to the northward progression of the AAIW from latitudes as low as 10∘ N up to at least 30∘ N. In contrast, the transport at 40∘ N is southward year-round, peaking in winter. Therefore, this behaviour could explain a special progression of the SAIW close to the Portuguese coast from high latitudes down to the GoC during this season.

Figure 10(a) Averaged percentages of each water mass resulting from the application of OMP analysis on WOA data, for each climatological month, at 35.5∘ N in the GoC. (b) Sverdrup transport at three locations close to the continental borders: south of GoC (30∘ N, 10∘ W), in the GoC (35.5∘ N, 10∘ W) and north of GoC (40∘ N, 10∘ W). (c) Monthly Ekman pumping in two zones: outside the GoC (between 35–36∘ N and 19–20∘ W) and inside the GoC (between 35–36∘ N and 7–8∘ W).

Figure 11Maps of surface winds and Sverdrup transport in January (top) and July (bottom). Right maps are a zoomed study region of surface Sverdrup transport.

Concerning the Ekman pumping, Fig. 12 shows its spatial distribution in the same two months of the climatological year, January and July, in the same domains considered in Fig. 10. Note that the zones with negative values of the Ekman pumping roughly depict the location of the gyres within the basin. In winter (i.e. January) the zone where convergence (negative Ekman pumping) is more important within the subtropical gyre reaches latitudes as high as 48∘ N, while in summer (i.e. July) this zone is more reduced and displaced to latitudes less than 36∘ N. Therefore, in winter, a more developed subtropical gyre may favour the increasing transport of high-latitude intermediate waters toward the GoC, while in summer a displacement towards the south gyre is not able to transport these high-latitude intermediate waters toward the GoC.

Besides the small-scale variations in Ekman pumping, we observe generalized divergence (positive Ekman pumping) near the eastern ocean margins all year-round. As the Ekman pumping is implicitly accounted for in the Sverdrup transport, we expect that divergence near the continents may be responsible for the local intensification of the meridional Sverdrup transport.

In order to present more detailed information about the time variability of the Ekman pumping at the latitude of the GoC, Fig. 10c shows the monthly climatological averages of this variable, inside the GoC, in a box limited 35–36∘ N and 7–8∘ W, and outside the GoC, in a box limited by 35–36∘ N and 19–20∘ W. Inside the GoC there is permanent divergence (positive pumping) in the Ekman layer caused by a small-scale cyclonic wind pattern existing in this area. This divergence, which is more intense during summer, would favour the displacement of the water masses underneath the Ekman layer toward the GoC, exerting a suction effect on them. Therefore, intermediate waters that arrive at a latitude close to the GoC could continue progressing northward thanks to this effect. Outside the GoC there is a permanent convergence (negative pumping), which is more intense during winter and summer. It is expected that during these seasons the dominant downwelling existing in the Ekman layer of this zone would not favour the transport of intermediate waters in that direction. However, in spring and autumn the intensity of these convergences decreases significantly, which could diminish the capacity of blocking the transport of intermediate waters in that direction.

In the following section we discuss all these preliminary results as well as the results attached in the related references in order to depict a conceptual model that allows explanation of the mechanisms that control the fluctuation of intermediate water masses in the GoC.

4.1 Extension and variability of the AAIW and its interrelation with other intermediate water masses

Presence of the AAIW in the GoC has been reported before (van Aken, 2000; Cabeçadas et al., 2002; Brogueira et al., 2004; Louarn and Morin, 2011; Preu et al., 2013; Hernández-Molina et al., 2014). There is also evidence of greater autumn AAIW presence near the African margin at least up to 32∘ N (Tsuchiya et al., 1992; Knoll et al., 2002; Machín and Pelegrí, 2009). Thus far, we remain uncertain whether this seasonal variability extends into the GoC.

In Sect. 3 we confirmed AAIW presence year-round along the middle slope from the northern Moroccan margin and into the GoC. We inferred certain seasonal AAIW variability featuring an autumnal approach to the continent, summer horizontal spread and offshore separation. Winter and particularly spring are characterized by a weaker AAIW presence.

Moreover, the results of the PCA on the water mass percentages allow the identification of clear interactions between the four water masses. In autumn a greater presence of the AAIW, coming from lower latitudes, seems to be related to a reduction in the presence of the SAIW and ENACW. This interaction also affects the MW, which is pushed by the AAIW toward the continental slope. In winter, the SAIW is the predominant water mass reducing the presence of the AAIW and ENACW and once again pushing the MW toward the continental slope. Note that in autumn a less dense MW entering the GoC (Millot et al., 2006) may be settled closer to the slope, making the AAIW penetration into the GoC easier.

The next step now is to investigate the physical mechanism that triggers these seasonal variations in the water masses' presence.

Machín and Pelegrí (2009) explained the arrival of the AAIW to latitudes around the Canary Islands in terms of the divergences produced by the Ekman pumping close to the African coast, and the subsequent stretching of the water column below, which promotes a northward movement of the intermediate waters in order to conserve its potential vorticity. However, the identified divergence regions were located too far from the African coast to explain the observed confinement toward the coast of the observed AAIW core. Perhaps the spatial resolution of 1∘ of the wind data used was too coarse to capture the small-scale variation of winds close to the continent. The importance of these small-scale variations of winds has been recognized in several studies (Kanzow et al., 2010; Machín et al., 2010; Pérez-Hernández et al., 2013; Velez-Belchi et al., 2017) in connection with the generation of baroclinic Rossby waves that propagate toward the interior ocean and may affect the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC).

Barrier et al. (2014), who have analysed the response of the North Atlantic subtropical gyre to the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) and other atmospheric regimes, conclude that this response involved important changes in meridional transport of water masses in this basin. For instance, a positive/negative NAO displaces the subtropical gyre to a higher/lower latitude. A gyre centred at a higher latitude favours a southward meridional transport of high-latitude water masses by the eastern boundary, while a gyre centred at lower latitude does not favour this southward transport of water masses from higher latitudes. In terms of the intermediate water masses we are dealing with, a positive NAO would prevent the entrance of the AAIW toward the GoC in favour of a greater SAIW arrival here, while a negative NAO would weaken the southward transport of the latter and favour the spread of the AAIW toward the GoC. While in our case we are not dealing with the NAO variability, it is worth noting that the effects on the subtropical gyre dynamics of a positive/negative NAO are fairly similar to the effects that a winter/summer wind forcing produces.

Keeping these previous results in mind and referring to the results presented in Sect. 3.3, we will propose a mechanism based on the seasonal variation of wind forcing in the North Atlantic that could explain the variations in the presence of the intermediate water masses in the GoC. Focussing on the greater presence of the AAIW in autumn, it seems that the following two types of processes are required:

- a.

processes that promote the transport of intermediate waters (AAIW and SAIW) from high latitudes toward the GoC,

- b.

processes that may favour the northward transport of intermediate waters when these have arrived at latitudes close to the GoC.

Regarding the first type of processes, we detach the small-scale variability of the wind stress curl close to the continents and its implications in the near-continent meridional Sverdrup transport. As shown in Fig. 10b, these transports southward along the Portuguese coast and northward along the African coast maintain a permanent direction during the whole year but become more intense from June to September along the African coast and from October to February along the Portuguese coast. Therefore, during summer the conditions for a decisive northward progression of the AAIW along the African coast are met, and this mechanism could be responsible for bringing the AAIW up to the Canary Islands region. However, since these transport processes diminish considerably in September, they may not be able to sustain the subsequent northward progression of the AAIW that could explain the observed maximum in the percentage of the AAIW along the slope of northern Morocco and the GoC attached in November. Therefore, it is then necessary to find additional processes that help sustain this northward progression up to the GoC. This leads us to the second type of processes.

Regarding the second type of processes, we will consider the seasonal variations of the Ekman pumping within GoC and in the zone of the subtropical gyre closest to GoC. Figure 10c shows these values for the different climatological months. Note that when the Ekman pumping becomes less negative to the west of the GoC, southward transport on the eastern branch of the gyre weakens and this could favour a greater spreading of the AAIW northwards. On the one hand, this weakening of the negative Ekman pumping in this zone is more pronounced during March–June and September–November. On the other hand, the Ekman pumping inside the GoC is positive during the whole year. As previously described, this permanent divergence in the Ekman layer caused by a small-scale cyclonic wind pattern existing in this area and more intense during summer would favour the displacement of the water masses underneath the Ekman layer toward the GoC, exerting a suction effect on them. Therefore, intermediate waters that arrive at a latitude close to the GoC could continue progressing northward inside the GoC thanks to this effect. Note that this Ekman pumping experiences a significant increase in November after having reduced its intensity during September and October.

4.2 Implication of the AAIW on the morphology of the continental margin

Intermediate water masses have been shaping the morphology along the northern Moroccan coast, the GoC and the Atlantic Iberian continental margins (see compilations in Hernández Molina et al., 2011, 2016). During the last decades numerous researchers and institutions have analysed the influence of both the MW and ENACW on the sea floor morphology with great detail, particularly within the GoC (e.g. Madelain, 1970; Melières, 1974; Nelson et al., 1993, 1999; Hernández-Molina et al., 2003, 2011, 2014, 2016; Llave et al., 2007; Garcia et al., 2009; Roque et al., 2012; Sánchez-Leal et al., 2017). These authors identified large depositional and erosional (contourite) features along the middle and upper continental slopes due to the vertical and lateral variation of the aforementioned intermediate water masses. The results obtained in the present study reveal clear seasonal variations of the AAIW and its interrelation with the SAIW, MW and ENACW. Nevertheless, changes in distribution of these intermediate water masses and the implications in particular of the AAIW for shaping the morphology and controlling sedimentation along the northern Moroccan coast, GoC and the Atlantic Iberian margins have not been considered so far and two new questions may arise: is there any influence of the AAIW along the continental slope at present, and has there been any influence of these intermediate water masses in the past?

Some recent papers have described the occurrence of bottom current features along the middle slope of the northern Moroccan margin, which do not fit well with present circulation of the ENACW and the MW and its associated interphases (pycnoclines). The onset of these features was related to both the action of deep tides and a branch of upper MW veering southwards off the Strait of Gibraltar along the Moroccan margin (e.g. Vandorpe et al., 2014, 2016; Lebreiro et al., 2018). Deep (barotropic and baroclinic) tides are important secondary processes amplifying the background water mass circulation generating local and smaller features but are not relevant for large regional depositional or erosional feature formation along continental slopes (Rebesco et al., 2014; Hernández-Molina et al., 2016). In contrast, a branch of upper MW veering southwards off the Strait of Gibraltar along the Moroccan margin is apparently against the Coriolis forces in the area (Baringer and Price, 1997, 1999) as well as the reported MW regional circulation (Sánchez-Leal et al., 2017). Northward flowing of a vigorous AAIW close to the margin, as reported here, could be considered as a plausible regional control factor in developing those features. However, this would require more detailed sedimentary, morphologic and paleoceanographic work in order to confirm this hypothesis.

Vertical variations of the MW and ENACW have been reported on the short (seasonal) term (e.g. Borenäs et al., 2002; Bellanco and Sánchez-Leal, 2016) and in longer geological cycles (Llave et al., 2006; Voelker et al., 2006; Rogerson et al., 2012; Hernández-Molina et al., 2016; Lofi et al., 2016 among other). The Pliocene and Quaternary (last 5.3 Myr) sedimentary evolution of the slope has been related to those vertical changes. For example, in glacial periods some authors have reported that the MW was flowing approximately 700 m deeper than today with associated changes in both Eastern North Atlantic Deep Water (ENADW) and North Atlantic Deep Water (NADW) (Schönfeld and Zahn, 2000; Schönfeld et al., 2003; Rogerson et al., 2012). An open debate about the relationship between the variation in the paths of these water masses and the sedimentary evolution along the northern Moroccan coast, GoC and the Atlantic Iberian continental margins has been ongoing since the recent Integrated Ocean Drilling Program (IODP) Expedition 339 in the GoC (Expedition 339 Scientists, 2012; Stow et al., 2013; Hernández-Molina et al., 2013, 2016). However, in this debate the influence of the AAIW in the past has not been taken into account.

The AAIW represents a cold intermediate water mass formed at the ocean surface in the Antarctic Convergence Zone/Antarctic Polar Front (between 50 to 60∘ S), mainly at the southwest of the southern tip of South America (Tomczak and Godfrey, 2003). After its formation the AAIW flows north as an intermediate water mass as far as 20∘ N, with trace amounts as far as 60∘ N. It continues northward until it encounters other intermediate water masses (Talley, 1999). This is the case for the AAIW in the Atlantic Ocean (and similar in the Indian Ocean), where this water mass has higher influence and is denser in comparison with the Pacific Ocean, where the AAIW is comparatively less important (Bostock et al., 2013). The formation and circulation of the AAIW is an important component of the upper branch of the AMOC that is associated with the transport of heat and salt within the Southern Hemisphere subtropical gyre (Stramma and England, 1999). Different authors have reported enhanced AAIW circulation during colder periods at different scales (e.g. Oppo and Horowitz, 2000; Curry and Oppo, 2005; Pahnke et al., 2008; Muratli et al., 2010; Makou et al., 2010; Jung et al., 2010; Wainer et al., 2012). For example, during the last glacial period, there is increased formation of intermediate water and the production of NADW is significantly weakened, and the NADW is replaced to a large extent by enhanced AAIW (Wainer et al., 2012), which circulated lightly with a main core ∼1100 m in a depth range between 900 and 1270 m (Makou et al., 2010). Therefore, vertical and lateral variations of the AAIW during glacial vs. interglacial periods have been reported (e.g. Viana et al., 2002; Bozzano et al., 2011; Preu et al., 2012, 2013; Voigt et al., 2013), and some authors have demonstrated that during the last decades the AAIW has been reduced, significantly warmer (0.058–0.158 ∘C per decade) and shoaling (30–50 dbar per decade) since becoming less dense (up to 20.03 kg m−3 per decade), due to global warming (e.g. Downes et al., 2010; Shmidtko and Johnson, 2012).

Therefore, based on all the above considerations we can conclude that the paths of the AAIW had to vary throughout the geological past at different scales, increasing during cold periods and decreasing and shoaling during warmer periods. The results presented in this paper are important and any future discussion on this subject should consider the lateral and vertical interaction of intermediate water masses in general and evaluate the role of AAIW in the past in particular, since its influence could be important, especially related to colder periods, in controlling the sedimentation along the slope. In that sense, it could contribute to higher siliceous production in determinate time periods as has been described with Expedition 339 in the GoC (Expedition 339 Scientists, 2012; Stow et al., 2013; Hernández-Molina et al., 2013, 2016).

The analysis of the seasonal variation of the intermediate water masses carried out in the GoC and adjacent areas has determined remarkable changes of the Antarctic Intermediate Water (AAIW) and the Subarctic Intermediate Water (SAIW). During autumn a greater presence of the AAIW, coming from lower latitudes, seems to be related to a reduction in the presence of the SAIW and the ENACW. This interaction also affects the Mediterranean Water (MW) which is pushed by the AAIW toward the upper continental slope. In the rest of the seasons, the SAIW is the predominant water mass reducing the presence of AAIW.

This seasonal variability in the interchange between these intermediate water masses can be explained based on the concatenation of several wind-driven processes acting during the different seasons. The summer intensification of the Sverdrup transports near the African coast makes the progression of AAIW possible from low latitudes up to latitudes above the Canary Islands. Subsequently, once the AAIW has reached latitudes close to the GoC, its northward transport is sustained due to a decrease in the intensity of negative Ekman pumping within the subtropical gyre west of the GoC, which presents its minimum intensity during autumn. This transport toward the GoC is also favoured by the permanent cyclonic wind system that dominates locally in the GoC, although it shows its highest intensity in the months of July to August. In November it again experiences a significant increase. The high percentage of the SAIW during winter, spring and summer could be explained by the permanent southward Sverdrup transport that occurs near the coast of the Iberian Peninsula, which favours the arrival of the SAIW to the GoC. From September onward this transport begins to weaken due to the arrival of the AAIW from the south and the deviation of part of the SAIW transport toward the eastern side of the subtropical gyre (west the GoC), where the intensity of the negative Ekman pumping is reduced between September and November.

Our results are important for a better understanding of intermediate water mass variability along the northern Moroccan coast, GoC and the Atlantic Iberian margins, but further paleoceanographic, sedimentary and morphological research is needed in order to decode changes in the geological past and determine how these water masses, in particular the AAIW, have been shaping the morphology and controlling the sedimentation along the northern Moroccan coast, the GoC and the Atlantic Iberian margins.

All data used in this study are compiled in Table 1.

Campaign information as well as data from the University of Cádiz (Golfo, Medout and Estrecho) are available upon request by contacting the correspondence author.

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/os-15-1381-2019-supplement.

All authors contributed to the design and development of the work.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

The authors thank Ocean Data View (Schlitzer, 2018), which helped make some graphics in this paper. The research was conducted in the framework of “The Drifters Research Group” of the Royal Holloway University of London (UK). Miguel Bruno was supported by the Salvador Madariaga mobility programme (grant PRX18/00441).

This research has been supported by CTM (projects CTM 2008-06399-C04/MAR (CONTOURIBER), CTM 2012-39599-C03 (MOWER), CTM2010-21229 (INGRES3), STOCAS (IEO 2009), CTM2014-59244-C3-2-R (DILEMA) CGL2016-80445-R (SCORE) and CTM2016-75129-C3-1-R (INPULSE) and the Salvador Madariaga mobility programme (grant no. PRX18/00441).

This paper was edited by David Stevens and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Álvarez, M., Pérez, F. F., Bryden H., and Ríos, A. F.: Physical and Biogeochemical Transports Structure in the North Atlantic Subpolar Gyre, J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans, 109, C03027, https://doi.org/10.1029/2003JC002015, 2004.

Ambar, I. and Howe, M.: Observations of the Mediterranean Outflow-I. Mixing in the Mediterranean outflow, Deep-Sea Res., 26A, 535–554, https://doi.org/10.1016/0198-0149(79)90095-5, 1979a.

Ambar, I. and Howe, M.: Observations of the Mediterranean Outflow-I. The deep circulation in the vicinity of the Gulf of Cadiz. Deep-Sea Res., 26A, 555–568, https://doi.org/10.1016/0198-0149(79)90096-7, 1979b.

Baringer, M. O. and Price, J. F.: Momentum and energy balance of the Mediterranean outflow, J. Phys. Oceanogr., 27, 1678–1692, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0485(1997)027<1678:MAEBOT>2.0.CO;2, 1997.

Baringer, M. O. and Price, J. F.: A review of the physical oceanography of the Mediterranean outflow, Mar. Geol., 155, 63–82, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0025-3227(98)00141-8, 1999.

Barrier, N., Cassou, C., Deshayes, J., and Treguier, A. M.: Response of North Atlantic Ocean Circulation to Atmospheric Weather Regimes, J. Phys. Oceanogr., 44, 179–201, https://doi.org/10.1175/JPO-D-12-0217.1, 2014.

Bellanco, M. J. and Sánchez-Leal, R. F.: Spatial Distribution and Intra-Annual Variability of Water Masses on the Eastern Gulf of Cadiz Seabed, Cont. Shelf Res., 128, 26–35, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csr.2016.09.001, 2016.

Borenäs, K. M., Wahlin, A. K., Ambar, I., and Serra, N.: The Mediterranean outflow splitting-a comparison between theoretical models and CANIGO data, Deep-Sea Res. II, 49, 4195–4205, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0967-0645(02)00150-9, 2002.

Bostock, H., Sutton, P., Williams, M. J. M., and Opdyke, B.: Reviewing the circulation and mixing of Antarctic Intermediate Water in the South Pacific using evidence from geochemical tracers and Argo float trajectories, Deep-Sea Res. I, 73, 84–98, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr.2012.11.007, 2013.

Bozzano, G., Violante, R. A., and Cerredo, M. E.: Middle slope contourite de posits and associated sedimentary facies off NE Argentina, Geo.-Mar. Lett., 31, 495–507, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00367-011-0239-x, 2011.

Brogueira, M. J., Cabeçadas, G., and Gonçalves, C.: Chemical Resolution of a Meddy Emerging off Southern Portugal, Cont. Shelf Res., 24, 1651–1657, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csr.2004.05.012, 2004.

Cabeçadas, G., Brogueira, M. J., and Gonçalves, C.: The Chemistry of Mediterranean Outflow and Its Interactions with Surrounding Waters, Deep-Sea Res. II, 49, 4263–4270, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0967-0645(02)00154-6, 2002.

Carracedo, L. I., Gilcoto, M., Mercier, H., and Pérez, F. F.: Seasonal Dynamics in the Azores-Gibraltar Strait Region: A Climatologically-Based Study, Prog. Oceanogr., 122, 116–130, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pocean.2013.12.005, 2014.

Cheng, H., Sinha, A., Wang, X., Cruz, F. W., and Edwards, R. L.: The Global Paleomonsoon as seen through speleothem records from Asia and the Americas, Clim. Dynam., 39, 1045–1062, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-012-1363-7, 2012.

Coulbourne, B. and Foote, K. D.: Variability of Stratification and Circulation on the Flemish Cap during the Decades of 1950s–1990s, J. Nortw. Atla. Fish. Sci., 26, 103–122, 2000.

Curry, W. B. and Oppo, D. W.: Glacial Water Mass Geometry and the Distribution of δ13C of ΣCO2 in the Western Atlantic Ocean, Paleoceanography, 20, 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1029/2004PA001021, 2005.

Dee, D. P., Uppala, S. M., Simmons, A. J., Berrisford, P., Poli, P., Kobayashi, S., Andrae, U., Balmaseda, M. A., Balsamo, G., Bauer, P., Bechtold, P., Beljaars, A. C. M., van de Berg, L., Bidlot, J., Bormann, N., Delsol, C., Dragani, R., Fuentes, M., Geer, A. J., Haimberger, L., Healy, S. B., Hersbach, H., Hólm, E. V., Isaksen, L., Kållberg, P., Köhler, M., Matricardi, M., McNally, A. P., Monge-Sanz, B. M., Morcrette, J.-J., Park, B.-K., Peubey, C., de Rosnay, P., Tavolato, C., Thépaut, J.-N., and Vitart, F.: The ERA-Interim Reanalysis: Configuration and Performance of the Data Assimilation System, Q. J. Roy. Meteorol. Soc., 137, 553–597, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.828, 2011.

Downes, S. M., Bindoff, N. L., and Rintoul, S. R.: Changes in the subduction of Southern Ocean water masses at the end of the twenty-first century in eight IPCC models, J. Climate, 23, 6526–6541, https://doi.org/10.1175/2010JCLI3620.1, 2010.

Expedition 339 Scientists: Mediterranean outflow: environmental significance of the Mediterranean outflow water and its global implications, IODP Preliminary Report, 339 pp., https://doi.org/10.2204/iodp.pr.339.2012, 2012.

Faugères, J. C., Mézerais, M. L., and Stow, D.: Contourite drift types and their distribution in the North and South Atlantic Ocean basins, Sed. Geol., 82, 189–203, https://doi.org/10.1016/0037-0738(93)90121-K, 1993.

Fratantoni, D. M.: North Atlantic surface circulation during the 1990s observed with satellite-tracked drifters, J. Geophys. Res., 106, 22067–22093, https://doi.org/10.1029/2000JC000730, 2001.

García, M., Hernández-Molina, F. J., Llave, E., Stow, D., León, R., Fernández-Puga, M. C., Díaz del Río, V., and Somoza, L.: Contourite erosive features caused by the Mediterranean Outflow Water in the Gulf of Cadiz: quaternary tectonic and oceanographic implications, Mar. Geol., 257, 24–40, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2008.10.009, 2009.

Gil, J., Sánchez, R., Cerviño, S., and Garabana, D.: Geostrophic Circulation and Heat Flux across the Flemish Cap, 1988–2000, J. Northw. Atla. Fish. Sci., 34, 61–81, https://doi.org/10.2960/J.v34.m510, 2008.

Hernández-Molina, F. J., Llave, E., Somoza, L., Fernández-Puga, M. C., Maestro, A., León, R., Medialdea, T., Barnolas, A., García, M., Díaz del Río, V., Fernández-Salas, L. M., Vázquez, J. T., Lobo, F., Alveirinho Dias, J. M., Rodero, J., and Gardner, J.: Looking for clues to paleoceanographic imprints: A diagnosis of the Gulf of Cadiz contournite depositional systems, Geology, 31, 19–22, https://doi.org/10.1130/0091-7613(2003)031<0019:LFCTPI>2.0.CO;2, 2003.

Hernández-Molina, F. J., Serra, N., Stow, D. A. V., Llave, E., Ercilla, G., and van Rooij, D.: Along-slope oceanographic processes and sedimentary products around the Iberian margin, Geo.-Mar. Lett., 31, 315, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00367-011-0242-2, 2011.

Hernández-Molina, F. J., Stow, D., Alvarez-Zarikian, C., and Expedition IODP 339 Scientists: IODP Expedition 339 in the Gulf of Cadiz and off West Iberia: decoding the environmental significance of the Mediterranean outflow water and its global influence, Sci. Dril., 16, 1–11, https://doi.org/10.5194/sd-16-1-2013, 2013.

Hernández-Molina, F. J., LLave, E., Preu, B.,Ercilla, G., Fontan, A., Bruno, M., Serra, N., Gomiz, J. J., Brackenridge, R. E., Sierro, F. J., Stow, D. A. V., García, M., Juan, C., Sandoval, N., and Arnaiz, A.: Contourite Processes Associated with the Mediterranean Outflow Water after Its Exit from the Strait of Gibraltar: Global and Conceptual Implications, Geology, 42, 227–230, https://doi.org/10.1130/G35083.1, 2014.

Hernández-Molina, F. J., Sierro, F. J., Llave, E., Roque, C., Stow, D. A. V., Williams, T., Lofi, J., Van der Schee, M., Arnáiz, A., Ledesma, S., Rosales, C., Rodríguez-Tovar, F. J., Pardo-Igúzquiza, E., and Brackenridge, R. E.: Evolution of the gulf of Cadiz margin and southwest Portugal contourite depositional system: Tectonic, sedimentary and paleoceanographic implications from IODP expedition 339, Mar. Geol., 377, 7–39, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2015.09.013, 2016.

Iorga, M. and Lozier, M. S.: Signatures of the Mediterranean outflow from a North Atlantic climatology 1. Salinity and density fields, J. Geophys. Res., 104, 25985–26009, https://doi.org/10.1029/1999JC900115, 1999.

Johnson, G. C.: Quantifying Antarctic Bottom Water and North Atlantic Deep Water Volumes, J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans, 113, 1–13, https://doi.org/10.1029/2007JC004477, 2008.

Jung, S. J. A., Kroon, D., Ganssen, G., Peeters, F., and Ganeshram, R.: Southern Hemisphere Intermediate Water Formation and the Bi-Polar Seesaw, PAGES News, 18, 36–39, 2010.

Kanzow, T., Cunningham, S. A., Johns, W. E., Hirschi, J. J.-M., Marotzke, J., Baringer, M. O., Meinen, C. S., Chidichimo, M. P., Atkinson, C., Beal, L. M., Bryden, H. L., and Collins, J.: Seasonal Variability of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation at 26.5∘ N, J. Climate, 23, 5678–5698, https://doi.org/10.1175/2010JCLI3389.1, 2010.

Knoll, M., Hernández-Guerra, A., Lenz, B., López Laatzen, F., Machín, F., Müller, T. J., and Siedler, G: The Eastern Boundary Current System between the Canary Islands and the African Coast, Deep-Sea Res. II, 49, 3427–3440, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0967-0645(02)00105-4, 2002.

Krauss, W., Fahrbach, E., Aitsam, A., Elken, J., and Koske, P.: The North Atlantic Current and its associated eddy field southeast of Flemish Cap, Deep Sea Res., 34, 1163–1185, https://doi.org/10.1016/0198-0149(87)90070-7, 1987.

Lavander, K. L., Davis, R. E., and Owens, W. B.: Mid-depth recirculation observed in the Labrador and Irminger seas by direct velovity measurements, Nature, 407, 66–68, https://doi.org/10.1038/35024048, 2000.

Lebreiro, S. M., Antón, L., Reguera, M. I., and Marzocchi, A.: Paleoceanographic and climatic implications of a new Mediterranean Outflow branch in the southern Gulf of Cadiz, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 197, 92–111, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2018.07.036, 2018.

Llave, E., Schönfeld, J., Hernández-Molina, F. J., Mulder, T., Somoza, L., Díaz del Río, V., and Sánchez-Almazo, I.: High-resolution sta tigraphy of the Mediterranean outflow contourite system in the Gulf of Cadiz during the late Pleistocene: the impact of Heinrich events, Mar. Geol., 227, 241–262, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2005.11.015, 2006.

Llave, E., Hernández-Molina, F. J., Somoza, L., Stow, D. A. V., and Díaz del Río, V.: Quaternary evolution of the contourite depositional system in the Gulf of Cadiz. Economic and paleoceanographic importance of contourites, Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ., 276, 49–79, https://doi.org/10.1144/GSL.SP.2007.276.01.03, 2007.

Lofi, J., Voelker, A. H. L., Ducassou, E., Hernández-Molina, F. J., Sierro, F. J., Bahr, A., Galvani, A., Lourens, L. J., Pardo-Igúzquiza, E., and Pezard, P.: Quaternary chronostratigraphic framework and sedimentary processes for the Gulf of Cadiz and Portuguese Contourite Depositional Systems derived from Natural Gamma Ray records, Mar. Geol., 377, 40–57, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2015.12.005, 2016.

Louarn, E. and Morin, P.: Antarctic Intermediate Water Influence on Mediterranean Sea Water Outflow, Deep-Sea Res. I, 58, 932–942, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr.2011.05.009, 2011.

Machín, F. and Pelegrí, J. L.: Northward Penetration of Antarctic Intermediate Water off Northwest Africa, J. Phys. Oceanogr., 39, 512–535, https://doi.org/10.1175/2008JPO3825.1, 2009.

Machín, F. J. and Pelegrí, J. L.: Interaction of Mediterranean Water Lenses with Antarctic Intermediate Water off Northwest Africa, Scientia Marina, 80(S1) 205–214, https://doi.org/10.3989/scimar.04289.06A, 2016.

Machín, F. J., Pelegrí, J. L., Fraile-Nuez, E., Vélez-Bechí, P., López-Laatzen, F., and Hérnandez-Guerra, A.: Seasonal Flow Reversals of Intermediate Waters in the Canary Current System East of the Canary Islands, J. Phys. Oceanogr., 40, 1902–1909, https://doi.org/10.1175/2010JPO4320.1, 2010.

Mackie, J.: Paleocurrent and paleoclimate reconstruction of the Western Boundary Undercurrent and Labrador Current on the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, thesis, Dalhousie University, 2005.

Madelain, F.: Influence de la topographie du fond sur l'ecoulement méditerrané en entre le Detroit de Gibraltar et le Cap Saint-Vincent, Cahiers Oceanographiques, 22, 43–61, 1970.

Makou, M. C., Oppo, D. W., and Curry, W. B.: South Atlantic Intermediate Water Mass Geometry for the Last Glacial Maximum from Foraminiferal Cd/Ca, Paleoceanography, 25, 1–7, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010PA001962, 2010.

Melières, F.: Recherches sur la dynamique sédimentaire du Golfe de Cádiz (Espagne), These de Doctoral, University of Paris A, 235 pp., 1974.

Millot, C., Candela, J., Fuda, J. L, and Tber, Y.: Large warming and salinification of the Mediterranean outflow due to changes in its composition, Deep Sea Res. I, 53, 656–666, 2006.

Muratli, J., Chase, Z., Mix, A. C., and McManus, J.: Increased Glacial-Age Ventilation of the Chilean Margin by Antarctic Intermediate Water, Nature Geosci., 3, 23–26, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo715, 2010.

Nelson, C. H., Baraza, J., and Maldonado, A.: Mediterranean undercurrent sandy contourites, Gulf of Cadiz, Spain, Sed Geol., 82, 103–131, https://doi.org/10.1016/0037-0738(93)90116-M, 1993.

Nelson, C. H., Baraza, J., Maldonado, A., Rodero, J., Escutia, C., and Barber Jr., J. H.: Influence of the Atlantic inflow and Mediterranean outflow currents on Late Quaternary sedimentary facies of the Gulf of Cadiz continental margin, Mar Geol., 155, 99–129, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0025-3227(98)00143-1, 1999.

Oppo, D. W. and Horowitz, M.: Glacial Deep Water Geometry?: South Atlantic Benthic Foraminiferal Cd/Ca and / 53C Evidence, 15, 147–160, https://doi.org/10.1029/1999PA000436, 2000.

Pahnke, K., Goldstein S. L., and Hemming S. R.: Abrupt Changes in Antarctic Intermediate Water Circulation over the Past 25,000 Years, Nature Geosci., 1, 870–974, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo360, 2008.

Pardo, P. C., Pérez, F. F., Velo, A., and Gilcoto, M.: Water Masses Distribution in the Southern Ocean: Improvement of an Extended OMP (EOMP) Analysis. Prog. Oceanogr., 103, 92–105, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pocean.2012.06.002, 2012.

Pearson, K.: On Lines and Planes of Closest Fit to Systems of Points in Space, Philosophical Magazine, 2, 559–572, 1901.

Peliz, A., Dubert, J., Santos, A. M. P., Oliveira, P. B., and LeCann, B.: Winter upper ocean circulation in the Western Iberian Basin–fronts, eddies and poleward flows: an overview, Deep Sea Res. I, 52, 621–646, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr.2004.11.005, 2005.

Peliz, A., Marchesiello, P., Santos, A. M. P., Dubert, J., Teles-Machado, A., Marta-Almeida, M., and LeCann, B.: Surface circulation in the Gulf of Cadiz: 2. Inflow–outflow coupling and the Gulf of Cadiz slope current, J. Geophys. Res., 114, C03011, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008jc004771, 2009.

Pérez, F. F., Mercier, H., Vázquez-Rodríguez, M., Lherminier, P., Velo, A., Pardo, P. C., Rosón, G., and Ríos, A. F.: Atlantic Ocean CO2 uptake reduced by weakening of the meridional overturning circulation, Nature Geosci., 6, 146–152, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo1680, 2013.

Pérez-Hernández, M. D., Hernández Guerra, A., Fraile-Nuez, E., Comas-Rodríguez, I., Benítez-Barrios, V. M., Dominguez-Yanes, J. F., Vélez-Belchí, P., and De Armas, D.: The Source of the Canary Current in Fall 2009, J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans, 118, 2874–2891, https://doi.org/10.1002/jgrc.20227, 2013.

Pickart, R. S., McKee, T. K., Torres, D. J., and Harrington, S. A.: Mean Structure and Interannual Variabillity of the Slopewater System South of Newfoundland, J. Phys. Oceanogr., 29, 2541–2558, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0485(1999)029<2541:MSAIVO>2.0.CO;2, 1999.

Pollard, R. T. and Pu, S.: Structure and Circulation of the Upper Atlantic Ocean Northeast of the Azores, Prog. Oceanogr., 14, 443–462, https://doi.org/10.1016/0079-6611(85)90022-9, 1985.

Poole, R. and Tomczak, M.: Optimum Multiparameter Analysis of the Water Mass Structure in the Atlantic Ocean Thermocline, Deep-Sea Res. I, 46, 1895–1921, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0967-0637(99)00025-4, 1999.

Preu, B., Schwenk, T., Hernández-Molina, F. J., Violante, R., Paterlini, M., Krastel, S., Tomasini, J., and Spieß, V.: Sedimentary growth pattern on the northern Argentine slope: The impact of North Atlantic Deep Water on southern hemisphere slope architecture, Mar. Geol., 329–331, 113–125, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2012.09.009, 2012.

Preu, B., Hernández-Molina, F. J., Violante, R., Piola, A. R., Paterline, C. M., Schwenk, T., Voigt, I., Krastel, S., and Spiess, V.: Morphosedimentary and Hydrographic Features of the Northern Argentine Margin: The Interplay between Erosive, Depositional and Gravitational Processes and Its Conceptual Implications, Deep-Sea Res. I, 75, 157–174, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr.2012.12.013, 2013.

Rahmstorf, S.: Thermohaline Ocean Circulation, Encyclopedia of Quaternary Sciences, 739–750, https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-44-452747-8/00014-4, 2007.

Raymo, M. E., Oppo, D. W., Flower, B. P., Hodell, D. A., McManus, J. F., Venz, K. A., Kleiven, K. F., and McIntyre, K.: Stability of North Atlantic Water masses in face of pronounced natural climate variability, Paleoceanography, 19, PA2008, https://doi.org/10.1029/2003PA000921, 2004.

Rebesco, M., Hernández-Molina, F. J., Van Rooij, D., and Wåhlin, A.: Contourites and associated sediments controlled by deep-water circulation processes: state of the art and future considerations, Mar. Geol., 352, 111–154, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2014.03.011, 2014.

Rhein, M.: Oceanography: Drifters reveal deep circulation, Nature, 407, 30–31, https://doi.org/10.1038/35024186, 2000.

Rios, A. F., Perez, F. F., and Fraga, F.: Water masses in the upper and middle North-Atlantic Ocean East of the Azores, Deep Sea Res. A, 39, 645–658, 1992.

Rogerson, M., Rohling, E. J., Bigg, G. R., and Ramirez, J.: Paleoceanography of the Atlantic-Mediterranean exchange: Overviewand first quantitative assessment of climatic forcing, Rev. Geophys., 50, RG2003, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011RG000376, 2012.

Roque, C., Duarte, H., Terrinha, P., Valadares, V., Noiva, J., Cachão, M., Ferreira, J., Legoinha, P., and Zitellini, N.: Pliocene and Quaternary depositional model of the Algarve margin contourite drifts (gulf of Cadiz, SW Iberia): seismic architecture, tectoni control and paleoceanographic insights, Mar. Geol., 303–306, 42–62, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2011.11.001, 2012.

Sabine, C. L., Feely, R. A., Gruber, N., Key, R. M., Lee, K., Bullister, J. L., Wanninkhof, R., Wong, C. S., Wallace, D. W. R., Tilbrook, B., Millero, F. J., Peng, T .H., Kozyr, A., Ono, T., and Ríos, A. F.: The Oceanic Sink for Anthropogenic CO2, Science, 305, 367–371, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1097403, 2004.

Sánchez-Leal, R. F., Bellanco, M. J., Fernández-Salas, L. M., García-Lafuente, J., Gasser-Rubinat, M., González-Pola, C., Hernández-Molina, F. J., Pelegrí, J. L., Peliz, A., Relvas, P., Roque, D., Ruiz-Villarreal, M., Sammartino, S., and Sánchez-Garrido, J. C.: The Mediterranean Overflow in the Gulf of Cadiz: A rugged journey, Scientific Reports, 3, eaao0609, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aao0609, 2017.

Schlitzer, R., Ocean Data View, available at: https://odv.awi.de, last access: October 2018.

Schönfeld, J. and Zahn, R.: Late glacial to Holocene history of the Mediterranean Outflow. Evidence from benthic foraminiferal assemblages and stable isotopes at the Portuguese margin, Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol., 159, 85–111, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-0182(00)00035-3, 2000.

Schönfeld, J., Zahn, R., and Abreu, L.: Surface and deep water response to rapid climate changes at the Western Iberian Margin, Glob. Planet. Chang., 36, 237–264, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0921-8181(02)00197-2, 2003.

Shmidtko, S. and Johnson, G. C.: Multidecadal Warming and Shoaling of Antarctic Intermediate Water, J. Climate, 25, 207–221, https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-11-00021.1, 2012.

Stein, M.: Oceanography of the Flemish Cap and Adjacent Waters, J. Northw. Atla. Fish. Sci., 37, 135–146, https://doi.org/10.2960/J.v37.m652, 2007.

Stow, D. A. V., Hernández-Molina, F. J., Alvarez Zarikian, C. A., the Expedition 339 Scientists: Proceedings IODP, 339, Integrated Ocean Drilling Program Management International, Tokyo, https://doi.org/10.2204/iodp.proc.339.2013, 2013.

Stramma, L. and England, M.: On the Water Masses and Mean Circulation of the South Atlantic Ocean, J. Geophys. Res., 104, 20863–20883, https://doi.org/10.1029/1999JC900139, 1999.

Stramma, L. and Siedler, G.: Seasonal changes in the North Atlantic subtropical gyre, J. Geophys. Res., 93, 8111–8118, https://doi.org/10.1029/JC093iC07p08111, 1988.

Talley, L. D.: Some aspects of ocean heat transport by the shallow, intermediate and deep overturning circulations, in: Mechanisms of Global Climate Change at Millennial Time Scales, Geophys. Mono. Ser., 112, American Geophysical Union, ed. Clark, Webb and Keigwin, 1–22, https://doi.org/10.1029/GM112p0001, 1999.

Talley, L. D.: Shallow, Intermediate, and Deep Overturning Components of the Global Heat Budget, J. Phys. Oceanogr., 33, 530–560, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0485(2003)033<0530:SIADOC>2.0.CO;2, 2003.

Tomczak, M. and Godfrey, J. S.: Regional Oceanography: an Introduction 2nd edn., 63–82, 2003.

Tomczak, M. and Large, D.: Optimum Multiparameter Analysis of Mixing in the Thermocline of the Eastern Indian Ocean, J. Geophys. Res., 94, 16141–16149, https://doi.org/10.1029/JC094iC11p16141, 1989.

Tsuchiya, M., Talley, L. D., Michael, S., and McCartney, M. S.: An Eastern Atlantic Section from Iceland Southward across the Equator, Deep Sea Res. A, 39, 1885–1917, https://doi.org/10.1016/0198-0149(92)90004-D, 1992.

Van Aken, H. M.: The Hydrography of the Mid-Latitude Northeast Atlantic Ocean I, The Deep Water Masses, 47, 757–788, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0967-0637(99)00092-8, 2000.

Van Aken, H. M.: The Hydrography of the Mid-Latitude Northeast Atlantic Ocean – Part III: The Subducted Thermocline Water Mass, Deep-Sea Res. I, 48, 237–267, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0967-0637(00)00059-5, 2001.

Vandorpe, T., Van Rooij, D., and de Haas, H.: Statigraphy and paleoceanography of a topography-controlled contourite drift in the Pen Duick area, southern Gulf of Cádiz, Mar. Geol., 349, 136–151, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2014.01.007, 2014.

Vandorpe, T., Martins, I., Vitorino, J., Hebbeln, D., García, M., and Van Rooij, D.: Bottom currents and their influence on the sedimentation pattern in the El Arraiche mud volcano province, southern Gulf of Cadiz, Mar. Geol., 378, 114–126, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2015.11.012, 2016.

Velez-Belchi, P., Perez-Hernandez, M. D., Casanova-Masjoan, M., Cana, L., and Hernandez-Guerra, A.: On the Seasonal Variability of the Canary Current and the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans, 122, 4518–4538, https://doi.org/10.1002/2017JC012774, 2017.

Viana, A. R., Hercos, C. M., Almeida Jr., W., Magalhães, J. L. C., and Andrade, S. B.: Evidence of bottom current Influence on the Neogene to Quaternary sedimentation along the Northern Campos Slope, SW Atlantic Margin, Deep-Water Contourite Systems: Modern Drifts and Ancient Series, Seismic and Sedimentary Characteristics. Geological Society, London, Memoirs 22, 249–259, https://doi.org/10.1144/GSL.MEM.2002.022.01.18, 2002.

Voelker, A. H. L., Lebreiro, S. M., Schönfeld, J., Cacho, I., Erlenkeuser, H., and Abrantes, F.: Mediterranean outflow strengthening during northern hemisphere coolings: a salt source for the glacial Atlantic?, Earth Planet Sc. Lett., 245, 39e55, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2006.03.014, 2006.

Voelker, A. H. L., Colman, A., Olack, G., Waniek, J. J., and Hodell, D.: Oxygen and hydrogen isotope signatures of Northeast Atlantic water masses, Deep Sea Res. II, 116, 89–106, 2015.

Voigt, I., Henrich, R., Preu, B. M., Piola, A. R., Hanebuth, T. J. J., Schwenk, T., and Chiessi, M.: A submarine canyon as a climate archive – Interaction of the Antarctic Intermediate Water with the Mar de Plata Canyon (Southwest Atlantic), Mar. Geol., 341, 46–57, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2013.05.002, 2013.

Wainer, I., Goes, M., Murphy, L. N., and Brady, E.: Changes in the Intermediate Water Mass Formation Rates in the Global Ocean for the Last Glacial Maximum, Mid-Holocene and Pre-Industrial Climates, Paleoceanography, 27, 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1029/2012PA002290, 2012.

Yashayaev, I. and Clarke, A.: Evolution of North Atlantic water masses inferred from Labrador Sea salinity series, Oceanography, 21, 30–45, https://doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2008.65, 2008.