the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Silicification in the ocean: from molecular pathways to silicifiers' ecology and biogeochemical cycles

Ivia Closset

J. Jotautas Baronas

Fiorenza Torricella

Félix de Tombeur

Bianca T. P. Liguori

Alessandra Petrucciani

Natasha Bryan

María López-Acosta

Yelena Churakova

Antonia U. Thielecke

Zhouling Zhang

Natalia Llopis Monferrer

Rebecca A. Pickering

Mathis Guyomard

Dongdong Zhu

The oceanic silicon (Si) cycle has undergone a profound transformation from an abiotic system in the Precambrian to a biologically regulated cycle driven by siliceous organisms such as diatoms, Rhizaria, and sponges. These organisms actively uptake Si using specialized proteins to transport and polymerize it into amorphous silica through the process of biosilicification. This biological control varies depending on environmental conditions, influencing both the rate of silicification and its ecological function, including structural support, defence, and stress mitigation. Evidence suggests that silicification has evolved multiple times independently across different taxa, each developing distinct molecular mechanisms for Si handling. This review identifies major gaps in our understanding of biosilicification, particularly among lesser-known silicifiers beyond traditional model organisms like diatoms. It emphasizes the ecological significance of these underexplored taxa and synthesizes current knowledge of molecular pathways involved in Si uptake and polymerization. By comparing biosilicification strategies across taxa, this review calls for expanding the repertoire of model organisms and leveraging new advanced tools to uncover Si transport mechanisms, efflux regulation, and environmental responses. It also emphasizes the need to integrate biological and geological perspectives, both to refine palaeoceanographic proxies and to improve the interpretation of microfossil records and present-day biogeochemical models. On a global scale, Si enters the ocean primarily via terrestrial weathering and is removed through burial in sediments and/or authigenic clay formation. While open-ocean processes are relatively well studied, dynamic boundary zones – where land, sediments, and ice interact with seawater – are increasingly recognized as key interfaces regulating global Si fluxes, though they remain poorly understood. Therefore, special attention is given to the role of dynamic boundary zones such as the interfaces between land and ocean, the benthic zone, and the cryosphere, which are often overlooked yet play critical roles in controlling Si cycling. By bringing together cross-discipline insights, this review proposes a new integrated framework for understanding the complex biological and biogeochemical dimensions of the oceanic Si cycle. This integrated perspective is essential for improving global Si budget estimates, predicting climate-driven changes in marine productivity, and assessing the role of Si in modulating Earth's long-term carbon balance.

- Article

(4835 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Silicon (Si) is the second most abundant element in the Earth's crust after oxygen and plays a crucial role in a variety of biological and biogeochemical processes (Struyf et al., 2009; Tréguer et al., 2021). It is a nutrient used by various terrestrial organisms, including plants and mammals, as well as a diverse range of marine life, such as unicellular diatoms and multicellular sponges (DeMaster, 2003; Farooq and Dietz, 2015). These organisms, collectively referred to as silicifiers, produce siliceous structures (also known as biogenic silica, bSi, or opal) through a biologically controlled process known as biosilicification (in the context of this paper biosilicification and silicification are used interchangeably). These silicifiers modulate Si cycling in the ocean through Si uptake and act as vessels of Si sedimentation and burial. While diatoms have received the most attention in biosilicification research due to their ecological importance, abundance, and relative ease to maintain in culture, they are not the only marine silicifiers. Recent studies have highlighted the importance of other key groups such as Rhizaria and sponges (Llopis Monferrer et al., 2020; López-Acosta et al., 2018; Maldonado et al., 2020). Silicon also contributes to other forms of biomineralization beyond siliceous structures made by silicifiers. It plays a role in the calcification of some coccolithophores (Durak et al., 2016; Ratcliffe et al., 2023a) and in the formation of silicified mouthparts in copepods (Naumova et al., 2015). In plants, Si is found at a wide range of concentrations and silicification contributes to the regulation of numerous biotic and abiotic stresses (Currie and Perry, 2007). Furthermore, the use of Si extends beyond eukaryotes, and it has been demonstrated that marine picocyanobacteria are able to accumulate important quantities of bSi (Baines et al., 2012). This growing body of work reveals that biosilicification is a widespread and evolutionary diverse phenomenon. Broadening our focus beyond diatoms is therefore essential to fully capture the complexity and global significance of biosilicification and its influence on the Si cycle in the ocean.

Particularly among non-model taxa such as protists, sponges, and picocyanobacteria, the physiological mechanisms underlying Si uptake, transport, and polymerization are still unknown, limiting our ability to generalize across taxa or predict functional responses to environmental change. Moreover, the role of silicifiers in shaping Si dynamics in the modern ocean and over geological timescales remains difficult to quantify. This is due to limited in situ measurements, unknown isotopic fractionation pathways, and the insufficient integration of biological diversity into global biogeochemical models. This includes a limited representation of how silicifiers influence other biogeochemical cycles, particularly the carbon (C) cycle, despite their major role in trapping C in surface waters and contributing to its long-term sequestration into the deep ocean via the biological pump (Laget et al., 2024; Ragueneau et al., 2006; Tréguer et al., 2018). Together, these knowledge gaps hinder our ability to assess how the Si cycle may respond to ongoing environmental changes, including global warming, ocean acidification, and shifts in nutrient availability.

In celebration of the Ocean Science Jubilee, we – a group of early-career researchers specializing in biosilicification and Si cycling – have collaborated to produce this review, which synthesizes current understanding of biosilicification across diverse organisms and its influence on the global marine Si cycle. We summarize existing knowledge on Si transport and polymerization at the cellular and molecular levels, the biological functions of bSi, and the environmental and ecological factors that regulate biosilicification. We also explore the taxonomic diversity of marine silicifiers and assess their roles in Si cycling across geological timescales and the modern ocean. Where relevant, we include examples from terrestrial ecosystems to highlight similarities and differences with marine silicifiers and identify opportunities for cross-system knowledge exchange. In addition, we examine key marine Si cycling processes in the different Earth interface zones (i.e., land-ocean, sediment-ocean, and ice-ocean), which are often underrepresented in global models but play a pivotal role in Si transformation and fluxes. In doing so, we highlight how stable (29Si and 30Si) and radioactive (32Si) isotopic tools have been instrumental in uncovering the contributions of these interfaces, as well as the broader biogeochemical impacts of silicifiers across time and space. Finally, we identify major knowledge gaps and unknowns across taxonomic, physiological, ecological, and biogeochemical domains, and propose a framework for future interdisciplinary research to address these challenges and advance our understanding of biosilicification and the global marine Si cycle.

Silicification involves the incorporation of inorganic Si into living organisms to form silica structures. This form of biomineralization represents a remarkable feat of biological engineering, characterized by the precise precipitation of amorphous silica within specialized cellular compartments. In the ocean, Si is found in dissolved form as silicic acid, which is readily available for biological uptake by organisms. The silicification process in marine environments occurs at relatively low temperatures, typically ranging from a few degrees Celsius in deep waters or high latitudes to around 30 °C in tropical surface waters. In contrast, synthetic silica formation in industrial or laboratory settings generally requires significantly higher temperatures and controlled conditions to facilitate precipitation and structural formation (De Tommasi et al., 2017). This stark difference highlights the efficiency of biological silicification, which occurs under ambient environmental conditions without the need for high temperatures or external catalysts (Livage, 2018).

Understanding silicification reveals the mechanisms by which organisms produce highly intricate and functionally optimized structures (see Box 1 for tools used to study biosilicification and Si uptake). Studying biological silicification not only deepens our knowledge of biomineralization and evolutionary adaptations but also has potential applications in biomimetic materials, nanotechnology, and sustainable engineering. Despite its broad distribution among marine lineages and the well-recognized benefits, such as protection from predation, light regulation, and enhanced structural support (Ghobara et al., 2019; Pančić et al., 2019; Petrucciani et al., 2022a), the specific requirements for Si and the mechanisms underlying its metabolism remains poorly defined in most living groups.

In marine environments, most work on silicification processes has focused on diatoms, admittedly due to their abundance and the relative ease of culturing them. In these organisms, silicification begins with the intracellular accumulation of Si, which must reach a sufficiently high concentration (1–340 mM) for deposition (Kumar et al., 2020a). Dissolved silica (dSi) from the environment is transported across the plasma membrane into the cell and concentrated in specialized intracellular compartments called silica deposition vesicles (SDVs, Fig. 1; Martin-Jézéquel et al., 2000), where controlled amorphous silica deposition occurs. Given the limited availability of dSi in modern oceans (ranging from under 2 µM in the surface water of central gyres to around 100 µM in polar regions; Tréguer et al., 1995), its uptake is considered the key step in silicification. While most studies have focused on dSi influx, an often-overlooked but crucial process is Si efflux from the cell, which helps prevent excessive intracellular Si accumulation that could lead to auto-polymerization and disrupt cellular function (Petrucciani et al., 2022b). Efflux has been proposed to operate through a mechanism similar to that of the influx but in reverse, although the role of sodium in this process remains unclear (Thamatrakoln et al., 2006).

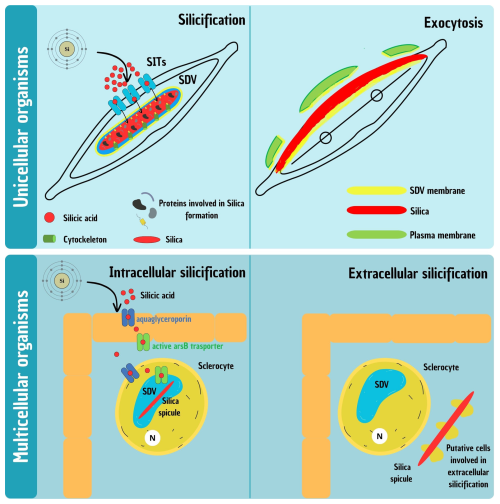

Figure 1Schematic representation of the silicification process in unicellular and multicellular organisms. (Top) Silicification in unicellular organisms, illustrated with a model diatom. Two main phases are shown: intracellular formation (left) and exocytosis (right) of the silica-based cell wall. In the first phase, dSi is transported via Si transporters (SITs) into the membrane-bound silica deposition vesicle (SDV), where polymerization forms the intricate valve structure. In the second phase, the mature silica element is exocytosed: the distal SDV membrane and plasma membrane gradually detach from the newly formed silica and disintegrate in the extracellular space, while the proximal SDV membrane remains and functions as the new plasma membrane, forming the interface between the cell and its environment. (Bottom) Silicification in multicellular organisms, illustrated using Hexactinellid sponges. Two phases are also depicted: intracellular formation (left) and extracellular elongation (right). During the first phase, dSi is transported to the silica deposition vesicle (SDV) inside specialized cells called sclerocytes, where proteins and enzymes regulate silica polymerization to form spicules. Once spicules outgrow the cell, formation continues extracellularly, though the molecular and cytological mechanisms governing this phase remain largely unresolved.

While silicification in unicellular organisms like diatoms is relatively well understood, the process becomes significantly more complex in multicellular organisms. Unlike single-celled organisms, where dSi is directly taken up from the environment, in multicellular systems, it must traverse multiple cellular barriers before reaching the site for silica deposition (Fig. 1). For example, in sponges, Si uptake and deposition involve several sequential steps. Sponges take up dSi from seawater through their outer epithelial cells and transport it internally across multiple cell layers to specialized silica-secreting cells called sclerocytes. Within sclerocytes, dSi is concentrated in SDVs, where polymerization occurs to form silica spicules, the structural elements of the sponge skeleton (Maldonado et al., 2020).

2.1 Silicon transport

Silicic acid, a small and uncharged molecule, can diffuse freely across membranes at environmentally relevant concentrations, making diffusion the main mode of uptake in diatoms (Thamatrakoln and Hildebrand, 2008). However, the average surface seawater silicic acid concentration in marine environments is 10 µmol L−1 (Conley et al., 2017; Frings et al., 2016), which is relatively low compared to the amounts required for biomineralization. To overcome this limitation, diatoms rely on specialized protein-mediated active transport systems to efficiently take up and concentrate Si within the diatom cell, ensuring the formation of silica-based structures. This process is tightly regulated, with specific proteins preventing premature silica polymerization during the initial stages of silicification.

The first Si transporters (SITs) were identified in the pennate diatom Cylindrotheca fusiformis (Hildebrand et al., 1997). These sodium-coupled active transporters facilitate silicic acid uptake from the environment and exhibit variations in cellular localization, binding affinity and transport rates. Diatoms possess multiple SITs (Durkin et al., 2016) with distinct gene expression patterns, potentially corresponding to different silicification roles (Thamatrakoln et al., 2006). Structurally, SITs typically contain 10 transmembrane domain segments (TMDs), arranged as two symmetrical 5 TMDs, and operate through a proposed transport model based on well-conserved amino acid motif pairs: EGXQ and GRQ (Thamatrakoln et al., 2006), which are believed to play key roles in substrate recognition and translocation across the membrane. The hydroxyl group of silicic acid binds to the carbonyl group of the glutamine in the EGXQ motif in the SIT proteins, triggering a conformational change that allows silicic acid to pass through the membrane (Knight et al., 2016).

SITs have been identified in many eukaryotic supergroups, such as chrysophytes (Likhoshway et al., 2006) and choanoflagellates (Marron et al., 2013). These SITs, along with those from diatoms, are proposed to have evolved from SIT-like (SIT-L) proteins through duplication and fusion events (Knight et al., 2023; Marron et al., 2016). SIT-L proteins resemble half-completed variations of SITs, containing only 5 TMDs and a single EGXQ-GRQ motif pair, and likely originated in bacteria (Marron et al., 2016). Although SIT-Ls share structural similarities with SITs, their role in silicic acid uptake remains uncertain. This uncertainty is reinforced by the observation that eukaryotic lineages containing SIT-Ls tend to be less silicified than those with SITs (Hendry et al., 2018; Marron et al., 2016; Ratcliffe et al., 2023b). Recently, a SIT-L protein from the coccolithophore Coccolithus braarudii was confirmed to actively drawdown silicic acid in a heterologous system (Ratcliffe et al., 2023b). However, this study also suggests that SIT-Ls are less efficient transporters than conventional SITs, as their silicic acid uptake remained undetectable even when using highly sensitive radioisotopic methods (32Si) typically used to measure uptake of silicic acid in diatoms and Rhizaria (see Box 1).

Box 1: Studying biosilicification and Si uptake: from molecular tools to radioisotope enrichment physiological experiments

Biosilicification is the molecular process by which organisms take up silicic acid and transform it into resistant, elastic biomaterials. The study of this process is crucial not only for understanding its biological and ecological significance, but also for unlocking sustainable solutions in material sciences. At the same time, insights gained at the molecular and cellular levels enhance our understanding of the marine Si cycle and improve the accuracy of global biogeochemical models. Recent advances in molecular and single-cell techniques are pushing the frontiers of this field. This toolbox highlights the key technologies currently used to investigate biosilicification.

A central focus in biosilicification research is the identification of molecular markers that signal the presence of this process. Among these, Si transporters are particularly informative. Due to their highly conserved (Hildebrand et al., 1997), these proteins are frequently identified using sequence similarity searches, hidden Markov models, and phylogenetic analyses to detect them in genome and transcriptome datasets (e.g. Durkin et al., 2016; Marron et al., 2016). Functional annotation and expression analyses can help confirm their roles in silicon transport and their regulation across different environmental conditions and taxa. However, silicon transporters are not necessarily the only proteins involved in this complex process. An indirect approach to studying silicification-related genes is to compare RNA transcript levels under limiting and excess silicate availability. By correlating the transcription of unknown genes with that of known silicifying proteins (e.g. Maniscalco et al., 2022; Thamatrakoln and Hildebrand, 2008), it is possible to identify potential candidates involved in silica metabolism. However, this approach is limited to the organisms that can be cultured or maintained in controlled conditions. Beyond genetic analyses, tools such as AlphaFold (Abramson et al., 2024; Mirdita et al., 2022) provide accurate structural predictions of proteins (Jumper et al., 2021). By modelling protein structures, it is possible to study active sites, binding interactions with silica precursors, and the molecular mechanisms driving silica deposition (Knight et al., 2023). Computational simulations and molecular docking further refine these insights by examining protein interactions with silicic acid and other biomolecules. In addition, structural alignment algorithms such as the Foldseek cluster (Barrio-Hernandez et al., 2023) enable large-scale comparisons, helping to identify domain families and detect remote structural similarities, shedding light on protein function and evolution in diverse organisms. Integrating these predictive approaches with experimental techniques such as electron cryomicroscopy, X-ray crystallography, and biochemical assays strengthens structural interpretations, deepening our understanding of biomineralization processes.

There are also qualitative methods for studying silicification, such as the use of fluorescent compounds. More recent developments have used PDMPO ((2-(4-pyridyl)-5-[(4-(2-dimethylamino-ethylaminocarbamoyl)methoxy)-phenyl]oxazole) in sponges, diatoms, and siliceous Rhizaria (McNair et al., 2015; Ogane et al., 2009; Schröder et al., 2004). This compound is incorporated into newly polymerized bSi under acidic conditions and emits a strong green fluorescence allowing for single-cell and mortality-independent information on silicification and growth rates (Leblanc and Hutchins, 2005; McNair et al., 2015; Shimizu et al., 2001). While this technique is not fully quantitative, these fluorescent markers provide valuable insight into the silicification process, helping to determine the spatial and temporal patterns of silica deposition and offering a deeper understanding of biomineralization dynamics.

The study of radioisotopes and stable isotopes also provides valuable insights into the dynamics of silicification, including uptake mechanisms, intracellular processing, and environmental influences. Silicon stable isotope tracing (30Si) has long been used to simultaneously quantify bSi production and dissolution in the ocean. (Fripiat et al., 2007; Nelson and Goering, 1977). Despite the long sample preparation times and complex instrumental analysis required, they offer a powerful tool to understand and quantify nutrient uptake mechanisms, especially when used in conjunction with other stable isotopes such as carbon (13C) or nitrogen (15N-nitrate or 15N-ammonium). Using secondary ion mass spectrometry, it is possible to obtain direct measurements of single cell uptake rates from the same sample (Olofsson et al., 2019). Beyond their use in ecosystem-scale studies, 30Si has also been directly applied to investigate biosilicification pathways. For instance, Marron et al. (2019) explored silicification in cultured choanoflagellates and highlighted potential similarities with sponge pathways, complementing mechanistic modelling of sponge Si isotope fractionation (Wille et al., 2010; updated by Maldonado and Hendry, 2025). In vitro experiments have also demonstrated the role of diatom proteins in fractionating Si isotopes, using the R5 peptide as a model for natural biomolecules involved in diatom silicification (Cassarino et al., 2021).

Due to its easy applicability and increased sensitivity compared to stable isotopes, Si radioisotope tracing (32Si) has gained increasing popularity in recent decades (Closset et al., 2021; Giesbrecht and Varela, 2021; Krause et al., 2019). It has been successfully applied to a variety of silicifying organisms, beginning with diatoms and later extended to others like Rhizaria (Llopis Monferrer et al., 2020). This technique may also be applicable to other organisms such as silicoflagellates and sponges, that can be maintained under controlled conditions.

While SITs and SIT-Ls play a crucial role in Si transport in unicellular silicifiers, the mechanisms governing this process in multicellular organisms appear to be fundamentally different, suggesting independent evolutionary pathways for silicification. In sponges, Si transport involves both passive and active transport mechanisms. Passive transport occurs via aquaglyceroporins, facilitating Si diffusion along its concentration gradient. Active transport is mediated by Na+-coupled co-transporters, enabling Si accumulation against its gradient. This dual transport system allows sponges to acquire dSi from seawater and transport it through the various cell barriers to the sites of spicule formation, where polymerization is initiated (Maldonado et al., 2020).

Research on Si transport in marine macrophytes is rather limited, despite recent evidence that they may play a key role in marine Si biogeochemistry (e.g. macroalgae; Yacano et al., 2021). In seagrasses, a protein called Siliplant1 has been associated with the vesicular transport of silica into the apoplast, the network of cell walls and intracellular spaces outside the plasma membrane, facilitating its incorporation into the extracellular matrix (Kumar et al., 2020b; Nawaz et al., 2020). For example, in Zostera marina, this mechanism likely facilitates the deposition of amorphous silica within cell walls and intercellular spaces that can persist even after harsh chemical treatments like alkaline digestion (Roth et al., 2025). Despite such evidence of “active Si transport”, more research is needed to better understand and characterize Si accumulation in marine macrophytes. In this respect, research on terrestrial plant species may provide valuable information. In particular, the tremendous variation in plant Si accumulation between terrestrial plant species (e.g. in leaves, Si concentration ranges from negligible amounts to over 10 % of dry weight; de Tombeur et al., 2023b) is classically attributed to the relative importance of passive and active transport (Liang et al., 2006). In short, the presence of specific influx and efflux channels encoded by specific genes would allow silicic acid uptake from the soil solution. Notably, a gene coding for cell-specific silica deposition has been recently identified in rice (Mitani-Ueno et al., 2023), shedding light on why certain taxa accumulate significantly more Si than others (Deshmukh et al., 2020; Hodson et al., 2005). However, such gene-based mechanisms remain poorly explored in marine plants. For instance, only a few proteins, such as Siliplant1, have been tentatively linked to Si transport in seagrasses (Kumar et al., 2020b; Nawaz et al., 2020), with homologues of other known Si transporter genes in plants yet to be found.

2.2 Silica polymerization

Extensive research has sought to understand how silicic acid is internalized by silicifying organisms. This process is still being actively studied to better understand its details, even though a lot of research has already been done in model diatoms (Hildebrand et al., 2018; Mayzel et al., 2021; McCutchin et al., 2025), as well as in sponges (Shimizu et al., 2015, 2024; Wang et al., 2012), and plants (Kumar et al., 2017a, b, 2021; Zexer et al., 2023). Silicification can occur intracellularly or extracellularly, but in all cases, specialized proteins guide the formation of silica into intricate nanoscale shapes.

Diatoms are characterised by their ability to exploit silicic acid to build a siliceous external cell wall, called a frustule. In diatoms, silica polymerization and frustule synthesis occur within SDVs. These vesicles have been visualized using transmission electron microscopy but have yet to be biochemically isolated (Hildebrand et al., 2018; Hildebrand and Lerch, 2015). The internal environment of the SDVs is slightly acidic, facilitating the polymerization of silicic acid into a gel-like silica network (Iler, 1979). Once inside the cells, yet unidentified binding components – potentially ligands or proteins – are thought to maintain silicic acid in solution and prevent premature autopolymerisation, which occurs at concentrations exceeding 2 mM (Martin-Jézéquel et al., 2000). Although polymerization was long assumed to be restricted to SDVs, recent discoveries in certain diatom species with elaborate silica appendages suggest that silicification may also occur extracellularly (Mayzel et al., 2021).

Silicon polymerization in diatoms is finely controlled by specialized proteins, with silaffins being the most extensively studied. These small, lysine- and serine-rich peptides catalyse silica polymerization, and the morphology of the resulting silica structure depends on their concentration and specific combination (Kröger et al., 1999, 2002). Other key proteins include long-chain polyamines (LCPAs), which catalyse silica polymerization in the presence of polyanions, and silacidins, proteins rich in serine and acidic amino acids that catalyse silica formation in the presence of LCPAs (Wenzl et al., 2008). Additional proteins contribute to specific steps in the process: (1) Cingulins, which are rich in tryptophan and tyrosine, localize to the girdle bands of diatom frustules; (2) Ammonium fluoride insoluble proteins (AFIM) are hypothesized to serve as pattern-forming base layers, and (3) silicalemma associated proteins (SAPs), including Silicanin-1, probably function as intermediaries between the cytoskeleton and the SDV (Görlich et al., 2019; Kotzsch et al., 2017; Tesson et al., 2017).

Silica polymerization in sponges is also biologically regulated and occurs both intracellularly and extracellularly. Generally, intracellularly polymerization occurs within SDVs located in sclerocytes: The formation of longer spicules (i.e. 250–300 µm), known as megascleres, is completed outside the cell, where silica is deposited externally (Schröder et al., 2007). Initial formation begins inside the sclerocyte but is transported out of the cell for further elongation, although the mechanisms underlying extracellular silicification remain poorly understood. Some studies suggest that sclerocytes may either release exosome-like, silica-rich vesicles (silicasomes) or physically migrate along the growing spicule, depositing silica directly without the need for protein mediation (Müller et al., 2013; Schröder et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2012). More recently, specific enzymes involved in extracellular silica deposition have been identified in hexactinellid sponges (Shimizu et al., 2024), suggesting a more complex and regulated process than previously assumed. However, some evidence also indicates that not all large hexactinellid spicules are completed extracellularly, challenging the assumption that size alone determines the transition from intra- to extracellular silicification (Mackie and Singla, 1997).

Most research on the enzymatic control of silica polymerization in sponges is relatively recent. The first enzyme identified in this process, silicatein, was described by Shimizu et al. (1998). Silicateins are cathepsin-like proteins that catalyze the hydrolysis and condensation of silicic acid, facilitating controlled silica polymerization (Müller et al., 2007; Riesgo et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2012). These enzymes regulate polymerization through their surface hydroxyl groups and exhibit species-specific variants that influence spicule morphology (Shimizu et al., 2015). Sponges also produce silicase, an enzyme that hydrolyzes silica under specific physiological conditions, potentially regulating silica solubility and remodeling during spicule growth (Ehrlich et al., 2010). Recent findings have identified additional proteins involved in silica polymerization, including silicatein-interacting proteins that modulate polymerization efficiency and structural integrity (Shimizu et al., 2024). Furthermore, collagen-like and lectin-like proteins may play auxiliary roles in silica deposition by modulating silica-protein interactions (Shimizu et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2012).

These biomineralization mechanisms evolved independently across the three classes of siliceous sponges. Demosponges rely on silicateins for silica deposition, whereas hexactinellid sponges lack silicateins and instead use hexaxilin for intracellular polymerization, along with glassin and perisilin for extracellular silica deposition that thickens spicules (Shimizu et al., 2015, 2024). Homoscleromorph sponges also display unique silica polymerization mechanisms, though the enzymes involved remain unidentified. The presence of unrelated enzymes in the Class Demospongiae and Hexactinellida, along with the distinct mechanisms observed in Homoscleromorpha, suggests that silicification has evolved multiple times independently in sponges (Shimizu et al., 2024). This convergent evolution underscores the adaptive significance of silica biomineralization in marine environments and highlights the diverse molecular strategies underpinning sponge silicification.

In plants, it is increasingly accepted that some cell wall polymers and proteins can initiate and control silicification (Zexer et al., 2023). For instance, the deposits of silica in the so-called silica cells found in many grass species are thought to be controlled by a protein named Siliplant1 (Kumar et al., 2020b; Zexer et al., 2023). These works have been pivotal to further understanding plant silicification and its potential links to other silicifying organisms (Kumar et al., 2020a).

2.3 Environmental and ecological influences on silicification

While the regulated flow of silica ions is crucial for biomineralization, it is not the only factor determining this process. Biomineralization is influenced by a complex interplay of environmental and ecological conditions. Although most studies have again focused on diatoms, similar mechanisms likely occur in other silicifying organisms. Silica deposition depends directly on dSi availability, with its limitation resulting in reduced silicification (Brzezinski et al., 1990; McNair et al., 2018; Shrestha et al., 2012). Lower temperatures have also been associated with increased silicification in diatoms (Durbin, 1977). Additionally, under replete silica conditions, silicification tends to be inversely correlated with growth rate, suggesting that other growth-limiting factors, such as the availability of iron (Fe2+ Fe3+) and zinc (Zn2+), may indirectly regulate frustule formation (Flynn and Martin-Jézéquel, 2000; Martin-Jézéquel et al., 2000). Light intensity further influences silicification in a complex manner, with increased silicification observed under both low (15 µmol photons m−2 s−1) and high (300 µmol photons m−2 s−1) light conditions (Petrucciani et al., 2023; Su et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2021). Other environmental factors, such as salinity (Vrieling et al., 2007) and pH (Hervé et al., 2012), can also modulate silicification, emphasizing the intricate interplay between environmental conditions and biomineralization.

Beyond its biochemical and environmental determinants, silicification plays a fundamental ecological role for silicifying organisms contributing to their overall fitness. In diatoms, frustules act as protection against predators due to high mechanical strength (Hamm et al., 2003). More heavily silicified diatoms are often rejected as food sources by copepods (Ryderheim et al., 2022), and increased silicification has been observed in response to predator presence (Petrucciani et al., 2022a; Pondaven et al., 2007). This suggests that the trophic chain can influence biomineralization processes and affect Si bioavailability. Similarly, some sponge species allocate more resources to skeleton formation as a defence strategy against predation, thereby enhancing their chances of survival (Ferguson and Davis, 2008; Rohde and Schupp, 2011). In terrestrial plants, silica deposition enhances resistance to herbivory by making leaves more abrasive and harder to digest (Hartley and DeGabriel, 2016; Massey et al., 2006). However, studies on silica-based defences in seagrasses are currently lacking, and it remains unclear whether these marine plants use similar strategies.

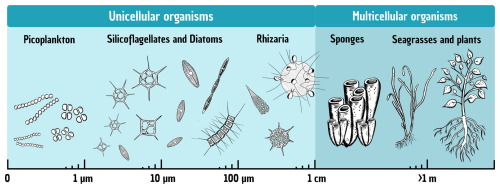

Over the past decade, research has transformed our understanding of the marine Si cycle by revealing that multiple groups of organisms contribute to silica dynamics, challenging the long-standing paradigm that diatoms were the sole important silicifiers. Historically, diatoms have been considered the primary drivers of bSi production and recycling in the ocean (Nelson et al., 1995; Tréguer et al., 1995; Tréguer and De La Rocha, 2013). However, recent studies have highlighted the significant role of other groups, such as Rhizaria and sponges (e.g. Laget et al., 2024; Llopis Monferrer et al., 2020; Maldonado et al., 2019). Additionally, many other taxa have been identified as interacting with Si (Baines et al., 2012; Churakova et al., 2023; Fig. 2), however, their contributions to Si cycling have yet to be quantified on regional and global scales. Beyond their contributions to Si cycling, the ecophysiological functioning of these groups is often poorly understood.

Understanding the taxonomic and functional diversity of silicifiers is not only crucial for ecological and evolutionary perspectives, but also provides essential inputs for functional trait models that incorporate silicic acid cycling and silicifying organisms (see also Box 3), thereby improving the predictive power of global biogeochemical models. For example, Naidoo-Bagwell et al. (2024) recently demonstrated this by extending the Earth system model cGEnIE with a diatom functional group, therefore requiring dSi, which improved the model's ability to reproduce observed nutrient fields, export production, and global distributions of diatoms. This expanding knowledge emphasizes the need to integrate multiple biological contributors into the Si biogeochemical cycle to better understand its functioning and enhance our ability to predict the effects of climate change and anthropogenic impacts (Tréguer et al., 2021).

Figure 2Total size range of silicifiers, from the smallest unicellular organisms (picoplankton) up to multicellular terrestrial plants.

The following paragraphs provide an overview of the main groups of silicifiers, ordered by their average size ranges and the current state of the art regarding their ecology and contributions to Si and C cycling.

3.1 Picoplankton

Picoplankton is a broad size category encompassing all planktonic or floating organisms measuring under 2 µm, though this is often extended to 3 µm due to the filter sizes used in field studies (Vaulot et al., 2008). The three main groups of picoplankton include heterotrophic bacteria, autotrophic bacteria (picocyanobacteria from the genera Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus), and autotrophic eukaryotes (picoeukaryotes). Picocyanobacteria and picoeukaryotes are typically grouped together under the moniker picophytoplankton. The discovery of large abundances of heterotrophic bacteria in the oceans, larger than previously estimated, first put these tiny unicellular organisms on the map (Hobbie et al., 1977). Since then, picoplankton have been discovered to be the base of the microbial food web, and their significant contributions in terms of biomass and productivity make them influential players in global biogeochemical cycling (Azam et al., 1983; Falkowski et al., 2008; Le Quéré et al., 2005).

Picoplankton are distributed widely in oceanic and freshwater environments, often described as ubiquitous or cosmopolitan. However, different picoplankton groups fill different environmental niches. For example, Synechococcus and picoeukaryotes prefer lower temperatures, while Prochlorococcus thrives in higher temperatures and lower latitudes (Buitenhuis et al., 2012; Flombaum et al., 2020; Visintini et al., 2021). Prochlorococcus abundances are notoriously high in oligotrophic (low nutrient) areas of the ocean, which can be explained by their competitive advantages (e.g. extremely small size, high diversity; Biller et al., 2015). Meanwhile, in nutrient-replete upwelling areas picoeukaryote growth is favoured (Li et al., 2023; Painting et al., 1993). Additional environmental factors that can affect picoplankton distribution patterns are light intensity and water mass events, as well as biological factors; such as the presence of predatory microplankton and viruses (Fuhrman, 1999; Otero-Ferrer et al., 2018; Sieradzki et al., 2019). Models predicting the impact of climate change on picoplankton suggest a global increase in picophytoplankton abundances, particularly in areas like the Arctic and Indian Oceans (Flombaum et al., 2020). In contrast, heterotrophic bacterial biomass in surface waters is expected to slightly decline, though this decrease is minor compared to the predicted reductions in microplankton and larger organisms (Heneghan et al., 2024; Kim et al., 2023). Overall, these findings indicate that future oceans will be increasingly dominated by picoplankton.

Picoplankton generally lack structural cellular components made of Si. However, some exceptions exist, such as Triparma laevis from the class Bolidophyceae, a close relative of diatoms that can measure less than 3 µm in size (Booth and Marchant, 1987; Kuwata et al., 2018; Yamada et al., 2014). Nevertheless, there is strong evidence that picoplankton interact with dSi in their environments regardless of whether or not they possess siliceous structures. Both extracellular and intracellular incorporation of dSi has been observed in heterotrophic bacteria. In some species of the bacterium Bacillus, dSi uptake occurs during an early stationary phase and is used for spore formation (Hirota et al., 2010). Environments where dSi is saturated, particularly geothermal hot springs, are sites of extracellular silica polymerization in different bacterial species (Inagaki et al., 2003; Lalonde et al., 2005; Phoenix et al., 2000). In the marine environment, Synechococcus cells from the Sargasso Sea were found to harbour highly concentrated quantities of bSi (Baines et al., 2012). BSi accumulation and/or dSi uptake has been demonstrated by marine Synechococcus strains in both the natural environment and in laboratory experiments (Aguilera et al., 2025; Krause et al., 2017; Ohnemus et al., 2016).

The effect of dSi on picoplankton has generally been considered neutral, as Synechococcus growth rates do not change when cultured in a wide range of dSi concentrations, though a new study demonstrates that high silicic acid concentrations can have negative effects on cell physiology (Ou et al., 2025). BSi accumulation has also been demonstrated by cultures of marine and brackish picoeukaryotes, including the smallest known marine eukaryote Ostreococcus tauri (Churakova et al., 2023). Curiously, in freshwater, Synechococcus bSi accumulation was not observed, suggesting that Synechococcus strains in this environment lack the same mechanism for dSi uptake or do not utilize dSi in ways similar to marine or brackish Synechococcus (Aguilera et al., 2025). A mechanistic explanation for Si uptake in these non-silicifying organisms can partially be explained by the SIT-Ls found in a limited number of bacterial and picocyanobacterial genomes (see Sect. 2 and Marron et al., 2016). However, in the majority of species and strains studied, the mechanisms by which picoplankton uptake and utilize dSi need further investigation and more relevant methodologies for studying picoplankton need development.

3.2 Silicoflagellates

Silicoflagellates are marine planktonic organisms belonging to the class Dictyochophyceae (Silva, 1982), order Dictyochales (Haeckel, 1887), which are characterised by a distinctive star-shaped silica skeleton (mostly 20–100 µm). They are exclusively marine unicellular protists and mostly considered photosynthetic, however, studies also show mixotrophic behaviour or non-photosynthetic bacteriovory (Eckford-Soper and Daugbjerg, 2016; Gerea et al., 2016; Sekiguchi et al., 2002). They have chromatophores for photosynthesis, but also possess pseudopodia, a typical feature of zooplankton, further complicating their classification (Sheath and Wehr, 2003).

Almost all of their protoplasm is located inside the skeleton, which is composed of hollow tubular elements joined at triple junctions to create a tridimensional star-shaped structure constructed outside of the cytoplasm. They have a single flagellum situated at the anterior end of the cell, which extends outside the skeleton itself (Chang et al., 2017a). In culture, they have occasionally been observed to shed their skeletons, especially at high cell abundances, and continue swimming either as flagellated cells or as unflagellated amoeboid cells. These cells can divide without cytokinesis and develop into multinucleate organisms (Henriksen et al., 1993; Van Valkenburg and Norris, 1970). This naked stage has since been described in nature and has been found to occasionally occur in significant blooms (Jochem and Babenerd, 1989; Moestrup and Thomsen, 1990). Reproduction occurs through binary fission (Van Valkenburg and Norris, 1970). In rare cases, the formation of double skeletons has been observed with the two skeletons joined at the basal ring (McCartney et al., 2014). Though other modes of reproduction have not been observed, the possibility of a sexual reproduction phase – similar to that of other phytoplanktonic organisms (e.g. diatoms) – cannot be ruled out. Silicoflagellate cell physiology remains largely understudied (Sancetta, 1990), partially due to challenges in maintaining them in culture. Despite the first successful culture in 1970 (Van Valkenburg and Norris, 1970), few cultures exist today, so individuals must be isolated from field samples for physiological experiments (Chang and Gall, 2016; Taguchi and Laws, 1985a).

Silicoflagellates first appeared in the Early Cretaceous (115 million years ago; McCartney et al., 2014) and showed great diversification throughout the Cenozoic (< 66 Ma) (McCartney et al., 1995, 2018). Their distinct skeleton structure and morphology are the basis for taxonomic identification (Malinverno, 2010) and due to their high abundance in sediments, they are used in micropalaeontology as proxies for palaeotemperature reconstructions (see Box 2 for further details). In the modern ocean, silicoflagellates are thought to be composed of four extant genera: Dictyocha (Ehrenberg, 1837), Octactism (Schiller, 1925), Vicicitus (Chang et al., 2012), and Stephanocha (Jordan and McCartney, 2015). However, as there is strong variability and plasticity in the skeleton (Dumitrica, 2014; McCartney et al., 2014; Van Valkenburg and Norris, 1970), in addition to the presence of the naked stage, this has led to considerable controversy regarding the number of species and genera (Chang et al., 2012, 2017a; Jordan and McCartney, 2015).

The abundances of different silicoflagellate species are influenced by variations in temperature and salinity, both in cultures (Henriksen et al., 1993; Van Valkenburg and Norris, 1970) and natural environments (Hernández-Becerril and Bravo-Sierra, 2001; Ignatiades, 1970; Rigual-Hernández et al., 2016; Sancetta, 1990). However, the responses of individual species to these environmental factors are not always consistent (Sancetta, 1990). Additionally, Malinverno et al. (2010) demonstrated that the same species, Stephanocha speculum, can present different varieties linked to their precise ecological niches, with some varieties (S. speculum var. monospicata, var. bispicata, and var. speculum) being found in open ocean conditions, while S. speculum var. coronata is associated with sea ice cover.

Silicoflagellates are most abundant in nutrient-rich areas of the ocean at high latitudes (Henriksen et al., 1993; Onodera et al., 2016; Takahashi et al., 2009) and in upwelling systems (e.g. Hernández-Becerril and Bravo-Sierra, 2001; Murray and Schrader, 1983; Sancetta, 1990). Their C uptake rates have been shown to be comparable to other phototrophic phytoplankton (e.g. for Dictyocha perlaevis; Taguchi and Laws, 1985b), though there are no studies to date comparing different species of silicoflagellates or changes in environmental conditions. Despite occasional high abundances, they are mostly considered insignificant contributors to primary production, planktic dynamics, and export fluxes. For example, in the Arctic Ocean, while they have been shown to contribute less than 1 % of the flux of particulate organic C (Onodera et al., 2016), they are regionally important prey for different copepod and krill species (Nakagawa et al., 2002; Passmore et al., 2006; Pasternak and Schnack-Schiel, 2001) as well as gelatinous grazers (Hiebert et al., 2025). Some species of silicoflagellates (e.g. Dictyocha spp.) have additional ecological significance through their role as harmful algae bloom (HAB) species with significant ichthyotoxicity (Esenkulova et al., 2020; Henriksen et al., 1993).

While the ecological relevance of silicoflagellates has been recognised, their mechanisms of silicic acid uptake remain unexplored, and their contribution to the Si and C cycles has yet to be quantified. While some previous studies focused on quantifying the regional contribution of silicoflagellates to Si export (Takahashi, 1989), their role in global Si cycling is entirely unconstrained (Tréguer et al., 2021).

3.3 Diatoms

Diatoms are a greatly diversified group of eukaryotic phytoplankton (Bacillariophyceae) belonging to the supergroup Stramenopiles (Bowler et al., 2010). They were first observed in 1703 (Round et al., 1990) and, since then, have attracted scientific interest across multiple disciplines, from taxonomists, oceanographers, geologists, engineers, and chemists, establishing them as the by far best-studied group of marine silicifiers. To date around 18 000 species of diatoms have been described, while their total diversity is estimated between 100 000 to 200 000 genera (Jeong and Lee, 2024; Mann and Vanormelingen, 2013). These photoautotrophic unicellular microorganisms are ubiquitous and can be found in all aquatic environments, including in sea ice, soils, lichens, biofilms, and airborne; denoting their extensive adaptive capabilities (Lohman, 1960).

Diatom taxonomy is based on frustule morphological traits and categorizes the species in two groups based on cellular symmetry: centric diatoms, with a radial symmetry, and pennate diatoms, with an elongated and bilateral symmetry (Round et al., 1990). Diatoms are thought to be secondary endosymbionts (Gentil et al., 2017; Morozov and Galachyants, 2019), meaning that their precursor was a eukaryote that phagocytized another eukaryote (which became an organelle), resulting in chloroplasts surrounded by 4 membranes. The earliest known fossil record of diatoms is still widely debated (Bryłka et al., 2023), but molecular clock and sedimentary evidence suggest an origin near the Triassic-Jurassic boundary (Nakov et al., 2018), when a greater availability of niches occurred. The gap in fossil records during this period has been hypothesized to relate to non-silicified or lightly silicified diatoms (Armbrust, 2009).

Diatoms are key primary producers in the oceans nowadays and their ability to adapt to different environmental conditions allows them to outcompete other phytoplanktonic groups during blooms. They are highly efficient primary producers constituting 40 % of marine primary production or 20 %–25 % of global Earth's primary production, despite representing only 1 % of Earth's photosynthetic organic biomass (Falkowski et al., 2004; Field et al., 1998). Their intricate frustules, provide improve fitness compared to other microorganisms (Martin-Jézéquel et al., 2000) including but not limited to providing mechanical protection, allowing hydrodynamic control of particle diffusion and advection, or increasing photosynthetic efficiency.

Nutrient uptake in diatoms is facilitated by their large vacuoles, which store essential elements like nitrogen (N) and Si. This storage capacity supports rapid growth during favourable conditions, contributing to their ecological success (Behrenfeld et al., 2021). Diatoms reproduce asexually through mitotic division, which progressively reduces cell size due to the constraints of their rigid silicious frustules. During each division, the daughter cell inherits one parental valve and forms a new, smaller valve within it, leading to a gradual decrease in cell dimensions over successive generations (Jewson, 1997). When cells approach a critical minimum size threshold, sexual reproduction is triggered to restore maximal cell dimensions. This process involves the formation of auxospores, specialized zygotic cells that expand and produce the initial large vegetative cells for the next cycle (Chepurnov et al., 2002). Auxospore formation is influenced by environmental factors such as light, nutrient availability, and cell density, as well as endogenous chemical signals (Assmy et al., 2006; Mouget et al., 2009). The interplay between asexual size reduction and sexual size restoration ensures diatom populations maintain their ecological and evolutionary success. This unique life cycle strategy contributes to their adaptability and widespread distribution in aquatic ecosystems.

Nutrient limitation, particularly of Si, Fe, and N, is a key driver of diatom growth and silica production. In oligotrophic gyres, low dSi concentrations (0.9–3.0 µM) limit silica production, despite rapid diatom growth rates. In nutrient-rich zones, diatom blooms significantly enhance silica and C export, with Si:C ratios ranging from 0.09 to 0.15 depending on species and environmental conditions (Brzezinski, 1985). Their regionally high abundance and ubiquitous distribution make them a key source of organic C for higher trophic levels, including zooplankton and fish larvae. Moreover, diatoms are an important vector for C export (∼ 20 %–40 %; Jin et al., 2006) due to their ability to form aggregates and their dense frustule, which improves sinking. As they sink, they rapidly transport organic matter to deeper ocean layers, and eventually are sequestered in sediments over geological time scales thanks to their siliceous frustules that enhance their preservation within the sedimentary records. Due to the well-defined ecological niches occupied by individual diatom species, their fossil assemblages serve as a reliable proxy for reconstructing past environmental conditions and tracking climate evolution (see Box 2 and e.g. Crosta et al., 2021; Torricella et al., 2025).

Box 2: Siliceous microfossils as markers of past and present oceanic conditions

Siliceous microfossils are widely used to reconstruct past environments, from deep geological times to the recent past. Among these, radiolarians, diatoms, and dinoflagellate cysts are particularly valuable for biostratigraphic studies, especially in environments where carbonate fossils are scarce or poorly preserved (Barron et al., 2014; Carvajal-Landinez et al., 2024; Iwai et al., 2025). Siliceous microfossils also serve as proxies in palaeoclimatic reconstructions, providing insights into water masses and environmental parameters such as sea ice cover, sea surface temperature (SST), and marine productivity (Torricella et al., 2025).

Diatoms play a key role in palaeoceanographic and palaeoclimatic reconstructions, particularly at high latitudes, where carbonate preservation is poor. Their distribution is controlled by surface water parameters including light availability, salinity, nutrient levels, temperature, sea ice extent, and the concentration of dissolved silicic acid (Torricella et al., 2022). Benthic diatoms are also influenced by substrate type and water depth, typically flourishing at around 100 meters where sunlight still reaches the seafloor (Round et al., 1990). Because diatom species occupy well-defined ecological niches, their fossil assemblages can be used to infer past oceanographic variability. However, only about 1 %–10 % of surface-dwelling diatoms are preserved in sediments. Their preservation is affected by silica dissolution during settling and at the seafloor, as well as by lateral transport, bioturbation, grazing, and diagenesis (e.g. Crosta and Koç, 2007; Ran et al., 2024). Despite these challenges, diatom assemblages provide crucial information on past surface ocean and climate conditions across a range of regions, including the Southern Ocean (e.g. Crosta et al., 2021), the Arctic (e.g. Oksman et al., 2019), and mid-latitudes (e.g. Bárcena et al., 2001). Exceptionally well-preserved, laminated diatom oozes – particularly those found in Southern Ocean coastal sites – enable high-resolution reconstructions of palaeoceanographic conditions (e.g. Alley et al., 2018; Leventer et al., 2006; Roseby et al., 2022). Seasonally laminated, diatom-rich sequences allow for annual-scale investigations of productivity and sedimentation processes (e.g. Leventer et al., 1993; Maddison et al., 2006; Pike and Kemp, 1997). In contrast, laminations formed by giant diatoms are often associated with specific oceanographic settings such as frontal systems and nutrient trapping, rather than seasonal cycles (Kemp et al., 2006). Stable isotope analyses have recently been applied to diatoms to strengthen palaeoenvironmental interpretations. Commonly measured isotopes include C and N in diatom-bound organic matter, as well as oxygen and Si in the siliceous frustules (Frings et al., 2024; Robinson et al., 2020; Swann et al., 2010). The oxygen isotope δ18O provides information on ice volume, temperature, and regional oceanographic conditions (e.g. Hodell et al., 2001; Shemesh et al., 2001), while δ30Si reflects the degree of dSi utilization by comparing uptake rates to ambient concentrations (Cardinal et al., 2005; De La Rocha et al., 1998; Varela et al., 2004). In addition, δ15N and δ13C serve as proxies for past ocean productivity (Crosta and Shemesh, 2002; Schneider-Mor et al., 2005).

Radiolarians, like diatoms, are widely employed in modern and palaeoceanographic studies due to their sensitivity to changes in SST, thermocline depth, nutrient availability, and water mass distribution (Hernández-Almeida et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2015, 2018). Their siliceous skeletons are well preserved in sediments and form distinct assemblages that record past temperature gradients, upwelling intensity, and ocean stratification (e.g. Civel-Mazens et al., 2024). Radiolarians can also serve as valuable palaeoceanographic proxies in regions where other silicifiers, such as diatoms, are rare or poorly preserved, particularly in certain deep-sea or oligotrophic sedimentary environments. Several studies have used both diatom and radiolarian assemblages to quantitatively estimate past sea temperature, salinity, and sea ice extent using transfer function techniques (Chadwick et al., 2022; Civel-Mazens et al., 2023; Crosta and Koç, 2007). These functions are based on three key datasets: (1) the modern species distributions in core-top sediments or water samples, (2) contemporary oceanographic parameters obtained from in situ measurements, and (3) fossil assemblages from sediment cores. A major limitation of this approach is the requirement for comprehensive coverage of all three datasets within the target study region.

Isotopic analyses can also be applied to radiolarians. The Si isotope δ30Si is used to reconstruct past dSi concentrations (Doering et al., 2021), while δ18O serves as a tracer for water temperature. Robinson et al. (2015) tested δ15N measurements on radiolarian tests, finding that it reflects the isotopic composition of their food sources. However, δ15N in radiolarians shows significant offsets compared to other siliceous microfossils, emphasizing the need to isolate radiolarian fractions carefully from other organisms. Abelmann et al. (2015) observed that δ18O and δ30Si from radiolarians and diatoms may not always align with changes in assemblages, but still offer valuable insights into silica uptake by different groups and changes in surface and subsurface water masses (down to ∼ 400 m).

Silicoflagellates, though less abundant and less studied than diatoms and radiolarians, are still useful in micropalaeontology as proxies for palaeotemperature and palaeoceanographic reconstructions (e.g. McCartney et al., 2022; Rigual-Hernández et al., 2016; Torricella et al., 2021). Sponges also contribute to siliceous microfossil records, with their spicules commonly preserved in marine sediments. Although assigning isolated spicules to specific sponge taxa is often difficult and sponge-derived material may be scarce in some environments such abyssal plains, they have been used to infer evolutionary, ecological, and environmental conditions (e.g. De Freitas Oliveira et al., 2020; Sim-Smith et al., 2017). Koltun (1960) first emphasized their utility in reconstructing salinity, temperature, and depth from sedimentary sequences. Sponge spicules now serve as valuable proxies for reconstructing a range of palaeoenvironmental conditions, including water flow regimes and velocities (Kuerten et al., 2013), pH (Pisera and Sáez, 2003), light availability (Harrison, 1974), temperature (Gaino et al., 2012), currents (Molina-Cruz, 1991), salinity (Cumming et al., 1993), and water depth (Łukowiak, 2016). Stable isotope analyses, particularly those focusing on δ30Si, are increasingly used on sponge silica to investigate Si cycling in ancient oceans (Egan et al., 2012). Sutton et al. (2013) demonstrated that δ30Si in sponge spicules offers a more accurate and integrated view of whole-ocean Si cycling than surface-dominated diatom records alone.

In conclusion, siliceous microfossils offer a diverse and powerful set of tools for palaeoenvironmental and palaeoclimatic reconstruction in a range of marine environments. Each group contributes unique ecological and geochemical information: diatoms, silicoflagellates, and radiolarians are particularly valuable for deciphering past surface and subsurface oceanic conditions, while sponge spicules provide complementary information on deeper water mass properties, benthic environments, and the Si cycle. Recent advances in stable isotope geochemistry have further expanded the potential of these microfossils, allowing for increasingly precise reconstructions of nutrient dynamics, temperature variations and Si utilisation.

3.4 Siliceous Rhizaria

Rhizaria, a diverse “supergroup” of unicellular eukaryotes, represents a fascinating and largely unexplored realm of biodiversity (Burki and Keeling, 2014). This supergroup is subdivided in three phyla: Endomyxa, Cercozoa, and Retaria. A key unifying morphological feature within these phyla is the production of very fine pseudopodia, often numerous, and typically supported by microtubules called filopodia (Adl, 2024). The major taxa of siliceous Rhizaria are represented by organisms belonging to the Cercozoa and Retaria phyla. Among Cercozoans with skeletons, those belonging to the Thecofilosaria, especially the Phaeodaria, possess skeletons that take the form of spicules or bars, which vary in size and shape. Although Phaeodaria were traditionally classified as Radiolaria due to morphological similarities, molecular phylogenetic analyses have demonstrated that they are not closely related to Radiolaria and are instead affiliated with the Cercozoa (Nikolaev et al., 2004). The phylum Retaria includes organisms with skeletons of various compositions, and is divided into Foraminifera and Radiolaria. The skeletons of Foraminifera are primarily made of calcium carbonate, while Radiolaria exhibit skeletons of various nature, including strontium sulfate (exclusive to the Acantharia class) or opaline silica (found in the Polycystine and Sticholonche classes).

Phaeodaria and Radiolaria, both characterized by an intricate siliceous skeleton, exhibit a remarkable range of lifestyles (solitary and colonial) and trophic diversity (heterotrophic or mixotrophic with photosynthetic symbionts). They also present great morphological variability, with sizes spanning from a few tens of micrometres to several millimetres, a gigantic size for protists. A key structural distinction lies in their skeletons. While Radiolaria skeletons are composed of robust, solid amorphous silica, Phaeodaria skeletons are hollow (Takahashi, 1983). Among the Polycystine Radiolaria, Spumellaria and Nassellaria are the most extensively studied groups, largely due to their robust skeletons and continuous fossil record dating back to the early Cambrian (De Wever et al., 2001). Spumellaria are characterized by concentric, generally spherical skeletons and were the first to appear in the Cambrian period. In contrast, Nassellaria display bilateral symmetry and possess conical skeletal structures with a limited number of spicules, first emerging in the Early Triassic (Anderson, 2001). Nassellaria are also known for their ability to form colonies, such as those seen in Collodaria, or large solitary skeletons, such as those of Orodaria (Nakamura et al., 2021).

Siliceous Rhizaria are widely distributed across the world's oceans, from tropical to polar regions, and are especially abundant in open-ocean environments. These protists are commonly found in the upper layers of the ocean, where sunlight supports the photosynthetic symbionts hosted by many Rhizaria species (Decelle et al., 2021). However, they are also well represented in deeper zones, including the mesopelagic (Biard and Ohman, 2020). Global assessments indicate that Rhizaria play a substantial role in zooplankton abundance, contributing up to 33 % (Biard et al., 2016). More recent studies, also using advanced imaging techniques to quantify large Rhizaria, indicate that they represent up to 1.7 % of mesozooplankton C biomass within the upper 500 m of the water column (Laget et al., 2024). Interestingly, Rhizaria biomass, particularly that of Phaeodaria, is more than twice as high in the mesopelagic than in the epipelagic layer (Laget et al., 2024). In marine ecosystems, Rhizaria have also been shown to dominate the eukaryotic community captured in sediment trap samples collected below the euphotic zone, as revealed by metabarcoding analyses (Gutierrez-Rodriguez et al., 2019; Preston et al., 2020).

The reproductive biology of Rhizaria remains poorly understood, primarily due to the challenges of maintaining most species under laboratory conditions. Although various life stages and lineage-specific cellular innovations have been observed in natural environments, their functional roles, as well as their physiological and ecological significance, remain largely uncharacterized (Rizos et al., 2024). Evidence suggests that both sexual and asexual reproduction occur across different Rhizaria lineages. Sexual reproduction involves the production and release of haploid gametes, which fuse to form a zygote with genetic material from both parent organisms. Asexual reproduction occurs by cell division during mitosis, resulting in two identical organisms. In colonial forms, asexual growth may occur through fission of the central capsules, contributing to colony expansion or fragmentation into multiple new colonies. In several species, reproduction involves the release of numerous flagellated swarmer cells that are considered to be gametes, produced via multiple nuclear divisions within the parent cell. These swarmers are released simultaneously and are presumed to fuse into zygotes, although the exact mechanisms of gamete fusion and early development remain poorly understood (Suzuki and Not, 2015). While the early ontogenetic stages are still not fully documented, the process of skeletal formation during growth has been extensively studied in several species under laboratory conditions (Anderson, 2001).

The widespread distribution of siliceous Rhizaria across marine ecosystems underpins their ecological importance in both food web dynamics and biogeochemical cycles. As basal components of planktonic communities, they serve as essential food sources and can act as vectors for energy transfer to higher trophic levels. Many Rhizaria host photosynthetic symbionts, enhancing primary production in oligotrophic waters (e.g. Llopis Monferrer et al., 2025). For instance, Collodaria are particularly abundant in nutrient-poor, tropical epipelagic zones and contribute significantly to zooplankton biomass (Faure et al., 2019). In deeper waters, Rhizaria play an important role in transforming sinking particles and serve as a key source of organic C in the mesopelagic zone (Laget et al., 2024; Lampitt et al., 2023). Their ecological significance extends to the Si cycle, as many Rhizaria species take up silicic acid from seawater to build their intricate skeleton (Llopis Monferrer et al., 2020) contributing up to approximately 20 % of the bSi production in the global ocean (Tréguer et al., 2021). Through both biological uptake and export, Rhizaria facilitate the vertical transport of silica and C to the deep ocean, reinforcing their role in long-term elemental cycling (Biard et al., 2018; Stukel et al., 2018). The opaline silica skeletons they produce also contribute to a rich and continuous fossil record since the Cambrian, more than 500 million years ago (Box 2; De Wever et al., 2001).

3.5 Sponges

Sponges belong to the phylum Porifera, which comprises approximately 9750 species classified into four distinct classes: Demospongiae, Calcarea, Hexactinellida, and Homoscleromorpha (Hooper and Van Soest, 2002; de Voogd et al., 2025). The largest and most diverse class, Demospongiae, accounts for nearly 84 % of all known sponge species. The remaining species are distributed among the classes Calcarea (8 %), Hexactinellida (7 %), and Homoscleromorpha (1 %; Van Soest et al., 2012). Sponges have been part of marine fauna since the late Precambrian (890–540 Ma) and are among the earliest known multicellular organisms on Earth (Wörheide et al., 2012). Since the Early Cambrian, many sponges have evolved siliceous skeletons, a trait present in over 80 % of extant species (Neuweiler et al., 2014). These sessile filter feeders inhabit a vast range of marine habitats, from intertidal zones to the deep sea, across all latitudes (Maldonado et al., 2017; Van Soest et al., 2012). While some species have broad distributions, others are highly specialized, restricted to specific substrates or environmental conditions such as deep-sea sponge reefs, coral-associated habitats, or high-silica environments.

Due to their ubiquity and substantial biomass, sponges are increasingly recognized as key functional components of ocean ecosystems (Bell, 2008; Bell et al., 2023; Folkers and Rombouts, 2020). Their complex body structures provide habitat for a diverse array of sessile and mobile organisms, making sponge-dominant communities biodiversity hotspots (Beazley et al., 2013; Klitgaard, 1995). Additionally, sponges contribute significantly to biogeochemical cycling by filtering and recycling dissolved organic and inorganic matter and nutrients, thereby influencing the fluxes of essential elements such as C, N, P, and Si (Busch et al., 2022; De Goeij et al., 2013; Maldonado et al., 2012).

Sponges reproduce both sexually and asexually. In sexual reproduction, gametes are released into the water column for external fertilization, although some species exhibit internal fertilization (Maldonado and Riesgo, 2008). Asexual reproduction occurs through budding, fragmentation, or gemmule formation, contributing to their resilience in dynamic environments (Battershill and Bergquist, 1990). Sponges exhibit a biphasic life cycle, alternating between a pelagic larval stage and a sessile adult stage. Larvae are typically short-lived, ranging from hours to a few days, and rely on passive dispersal by ocean currents (Maldonado and Abdul Wahab, 2025). Upon settlement, larvae undergo metamorphosis into juvenile sponges, attaching to a substrate where they develop into mature, filter-feeding adults. Sponges generally live for several years to decades, with some species known to survive even for centuries (Leys and Lauzon, 1998; McGrath et al., 2018; McMurray et al., 2008).

For decades, the role of sponges in Si cycling was considered negligible. However, recent research has demonstrated their significant contribution at both regional and global scales (López-Acosta et al., 2022; Maldonado et al., 2019, 2021). Siliceous sponges actively assimilate large amounts of dSi, transforming it into bSi for skeletal formation. Upon their death, this silica can either dissolve back into the water column, sustaining other silicifiers, or be buried in sediments, influencing long-term silica sequestration. This process is particularly relevant in deep-sea sponge grounds and continental shelf ecosystems, where sponges are particularly abundant and act as major reservoirs facilitating benthic-pelagic coupling of the Si cycle (Tréguer et al., 2021). Furthermore, sponge-mediated Si cycling interacts with other major biogeochemical cycles such as those of C and N, as sponge excretion and microbial symbionts further contribute to matter and nutrient transformations (Busch et al., 2022; Maldonado et al., 2012).

3.6 Plants

In the last two decades, an important number of functions has been assigned to leaf silicification (Cooke and Leishman, 2016; Johnson et al., 2024; de Tombeur et al., 2023b), including for wetland and aquatic plants (Schoelynck et al., 2012; Schoelynck and Struyf, 2016). Interestingly, species that are emergent (only basal stem parts in the water) and submerged tend to accumulate more Si compared with species that mostly have floating organs (Schoelynck and Struyf, 2016). In emergent and submerged species, silicification could be used to increase strength in order to overcome different physical stresses (gravity, horizontal force, etc.; Schoelynck and Struyf, 2016). In floating species, on the contrary, silicification is considered less important because they are less impacted by hydrodynamics forces (Schoelynck and Struyf, 2016). Beyond the structural role of Si in wetland and aquatic species, Si is also used for resisting herbivory. For instance, the bSi concentration of different N. lutea individuals is negatively correlated with the damages caused by Galerucella nymphaeae (Schoelynck and Struyf, 2016). Whether silicification is an adaptation or exaptation to grazing is, however, still debated (de Tombeur et al., 2023b). While trait-based approaches have recently advanced our understanding of silicification strategies in plants, applying similar frameworks to other marine silicifiers such as diatoms remains challenging due to fundamental differences in morphology and silica utilization patterns (see Box 3).

Box 3: Trait-based approaches to understand the functions of silicification: are diatoms and plants the same?

Why do species or families invest more in silicification than others? Does silicification involve trade-offs with key ecological strategies? What are the costs and benefits of silicification? In land plants, integrating Si concentrations in trait-based approaches has recently proved useful to answer those fundamental questions about Si utilization (de Tombeur et al., 2023b). The question arises as to whether the same approaches could be used in marine silicifiers such as diatoms. In plants, measuring organ-scale Si concentration is relatively easy and offers a reasonable proxy for the degree of silicification, which can then be linked to other functional traits (de Tombeur et al., 2023a, 2025). In diatoms, we hypothesize that it is probably more the shape of silica-based skeletons that is linked to specific functions and associated trade-offs, and less the bulk diatom Si concentrations per se. As such, using only diatom Si concentrations, as done in plants, may not be sufficient to infer specific functions associated with silicification given the large diversity of silicification patterns. Instead, diatom shapes should be involved in current trait-based frameworks. Beyond silicification, current trait-based approaches in diatoms mostly rely on metabolic traits (e.g. nutrient uptake rates; Ács et al., 2019; Litchman, 2022), and less on morphological and chemical traits that are reasonably easy to measure, as it the case in plants (e.g. leaf thickness, leaf area, leaf N concentration). This major difference explains why trait-based approaches to better understand the role and evolution of silicification will probably not follow the same paths for diatoms and plants. Maintaining a constant dialog between trait-based ecologists working on both types of silicifiers is, however, essential.

In coastal systems, seagrass meadows provide vital ecological services, including nutrient cycling and climate regulation, and may influence Si dynamics in estuarine and marine environments. Despite their ecological importance and proximity to riverine Si inputs, the role of seagrasses in the Si cycle remains understudied. While the elemental composition of seagrass leaves has been widely analysed for macronutrients like N and phosphorus, only a few studies have quantified Si concentration in seagrass (see Herman et al., 1996; Roth et al., 2025; Vonk et al., 2018), leaving an important gap in understanding their role in biogeochemical Si cycling. The mechanisms of Si accumulation in seagrasses are not yet fully understood, but recent research in Zostera marina has identified phytoliths in its roots, stems, and leaves (Rong et al., 2024) and suggests a functional dSi uptake pathway involving the Slp1 protein and vesicular transport (Kumar et al., 2020b; Nawaz et al., 2020). By measuring bSi in four families of seagrass species, Vonk et al. (2018) showed that Z. marina tends to accumulate more silica than other seagrasses, though still less than freshwater vegetation. This species displays a relatively low bSi content but may still play a significant role in coastal Si cycling, especially since some of its Si resists dissolution and could buffer the transport of dSi to the ocean (Roth et al., 2025).

Understanding the diversity, biology, and ecological roles of silicifying organisms is essential to contextualize their broader influence on Earth system processes. In the following section, we examine how the biogeochemical cycle of Si has evolved from abiotic to biologically mediated control, highlighting the role of silicifying taxa in transforming Si fluxes, sedimentation patterns, and ocean chemistry across Earth's history and into the modern era.

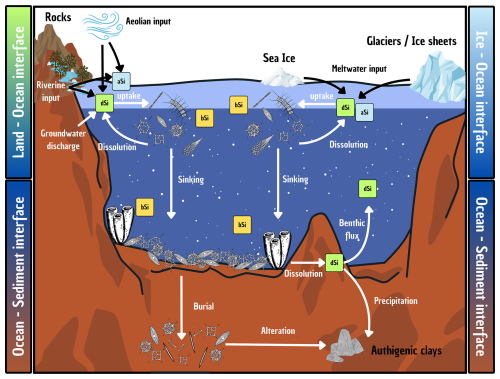

4.1 Evolution of the silicon cycle across geologic time

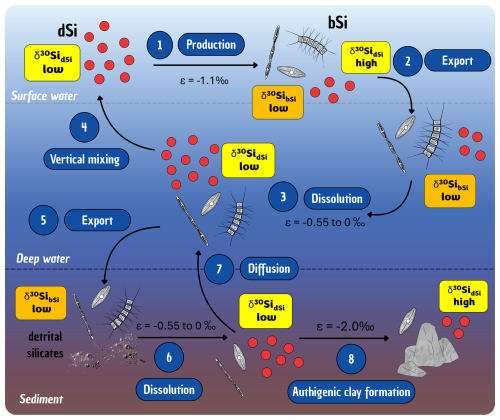

Researchers began trying to better understand the evolution of the oceanic Si cycle just over three and a half decades ago (Maliva et al., 1989; Siever, 1991, 1992), with considerable effort since then focused on standing stocks and how the current cycle evolved (Conley et al., 2017; Trower et al., 2021). The modern oceanic Si cycle is relatively well studied (Tréguer et al., 2021), with Si mainly occurring in the marine environment in the form of dSi. The amount of dSi available in the ocean is a balance between inputs (e.g. rivers, aeolian, submarine groundwater, glaciers, and hydrothermal activity), biological circulation via silicifiers (e.g. diatoms, sponges, and Rhizaria), and removal (e.g. burial, biogenic uptake, and secondary formation; see Fig. 3). Overall, modern oceanic dSi concentrations are low, averaging less than 10 µM at the surface and around 70 µM in the deep ocean (Gouretski and Koltermann, 2004; Tréguer et al., 1995), primarily regulated by biological activity, but this has not always been the case. In the absence of silicifiers, the oceans must have had higher dSi concentrations in the Precambrian compared to the Phanerozoic (Maliva et al., 2005). Understanding the evolution of silicifiers is therefore crucial to understanding the geologic history of the oceanic Si cycle.

Figure 3Schematic representation of the Si cycle in the modern global ocean, illustrating key processes occurring at the interface between the ocean and other environments (e.g. sediments, land, ice). Particular attention is given to the transformations and transfers of Si in both dissolved (dSi; green boxes) and particulate forms (e.g. biogenic silica, bSi – yellow boxes – and amorphous silica, aSi – blue boxes) as it moves between the surface and deep ocean. Details are given in Sect. 4.3 and quantification of the fluxes are presented in Table 1.